From the Chicago Reader (September 11, 1992). — J.R.

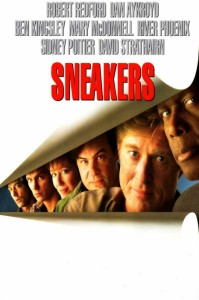

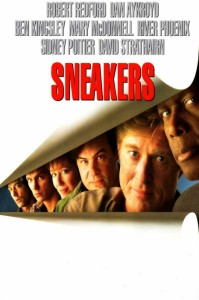

SNEAKERS

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Phil Alden Robinson

Written by Robinson, Lawrence Lasker, and Walter F. Parkes

With Robert Redford, Dan Aykroyd, Ben Kingsley, Mary McDonnell, River Phoenix, Sidney Poitier, David Strathairn, Timothy Busfield, George Hearn, Eddie Jones, and Stephen Tobolowsky.

Although Sneakers has plenty of artful craft, the principal pleasure of Phil Alden Robinson’s new feature has less to do with art than it does with old-fashioned entertainment. Robinson, you may recall, wrote and directed In the Mood (1987) and the much more successful and better known Field of Dreams (1989), two movies whose basic appeal was founded in nostalgia. Though everything after the prologue and credits in Sneakers is set in the present, the movie reminds us of what movie entertainment used to be about, especially during the 50s and 60s, before inflated ideas about art and significance took over. (I suspect that many of the movie’s high-tech details come from producers and cowriters Walter F. Parkes and Lawrence Lasker, who together wrote the script of WarGames.)

Sneakers can be described in many ways: as a caper movie, a lightweight thriller, a high-tech fairy tale, a boys’ adventure, or a Hitchcockian jaunt dating back to the period before Hitchcock was regarded as a serious metaphysical artist — that is, either before he left England for Hollywood or up to the time he made North by Northwest, but in any case before the weighty French interpretations of his thrillers became coin of the realm. Read more

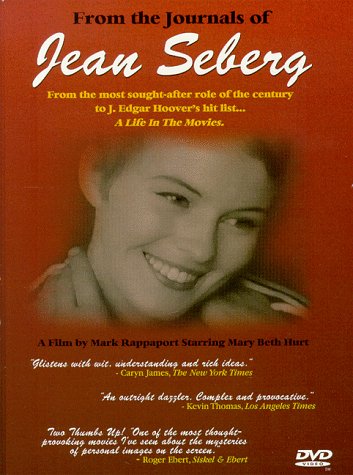

From the Chicago Reader (January 12, 1998). — J.R.

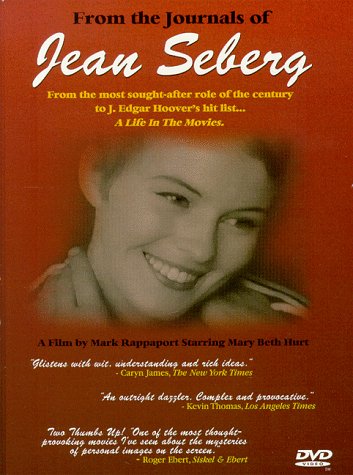

From the Journals of Jean Seberg

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed and written by Mark Rappaport

With Jean Seberg and Mary Beth Hurt.

For most of the remainder of this month the Film Center is presenting the U.S. theatrical premiere of Mark Rappaport’s From the Journals of Jean Seberg, and using this occasion to show some other important programs as well. We had revivals of Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless, featuring one of Seberg’s key early performances, and Carl Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), both important touchstones in Rappaport’s film — the second as a cross-reference to Seberg’s first film, Saint Joan. This week, in addition to seven showings of From the Journals of Jean Seberg (to be followed by four more over the next couple of weeks), there are two screenings of a brand-new print of one of Rappaport’s best narrative features, The Scenic Route (1978), along with his remarkable 36-minute tour de force Exterior Night (1994) — a noirish narrative about film noir in which actors filmed in color walk around inside vintage black-and-white Warners sets and locations from the 40s and 50s, shot originally on high-definition video in Germany, and recently transferred to 35-millimeter film. Read more

From Cineaste (Summer 2010, Vol. XXXV, No. 3). — J.R.

Robert Bresson: A Passion for Film

By Tony Pipolo. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010. 407 pp. Hardcover: $125 and Paperback: $29.95.

“I do not like to show sex crudely on the screen,” Orson Welles declared in a 1964 interview, pursuing an argument that he also made on other occasions. “Not because of morality or puritanism; my objection is of a purely aesthetic order. In my opinion, there are two things that can absolutely not be carried to the screen: the realistic presentation of the sexual act and praying to God. I never believe an actor or actress who pretends to be completely involved in the sexual act if it is too literal, just as I can never believe an actor who wants to make me believe he is praying.”

It’s an argument that frequently comes to mind when I ponder a certain critical impasse that we often face in considering the films of Robert Bresson, largely due to the dearth of biographical information that we have about him. For a filmmaker whose erotic and spiritual preoccupations seem equally pronounced, Bresson frequently poses the conundrum of how we fill in certain psychological blanks in his characters as well as how we describe and understand matters of the flesh as well as the spirit, as we perceive these matters through what he liked to call his cinematography. Read more