From the Chicago Reader (September 14, 2007). — J.R.

Released in 1953, this glitzy, entertaining MGM art movie is fascinating partly because it testifies to the influence of patriarchal French existentialism on American pop culture. Gottfried Reinhardt (son of Berlin stage director Max Reinhardt) directed the first of its three episodes, about a ballet dancer with a heart condition (Moira Shearer) who’s driven to the breaking point by an enthusiastic choreographer (James Mason), and the third, a suspenseful tale about Parisian trapeze artists (Kirk Douglas and Pier Angeli) who learn to commit to one another in a post-Holocaust context by taking inordinate risks. But the best episode is Vincente Minnelli’s fantasy about a disgruntled boy in Rome (Ricky Nelson) who, with the help of an American witch (Ethel Barrymore), becomes a grown man (Farley Granger) long enough to date his French nanny (Leslie Caron). 122 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

Written for The Unquiet American: Transgressive Comedies from the U.S., a catalogue/ collection put together to accompany a film series at the Austrian Filmmuseum and the Viennale in Autumn 2009. — J.R.

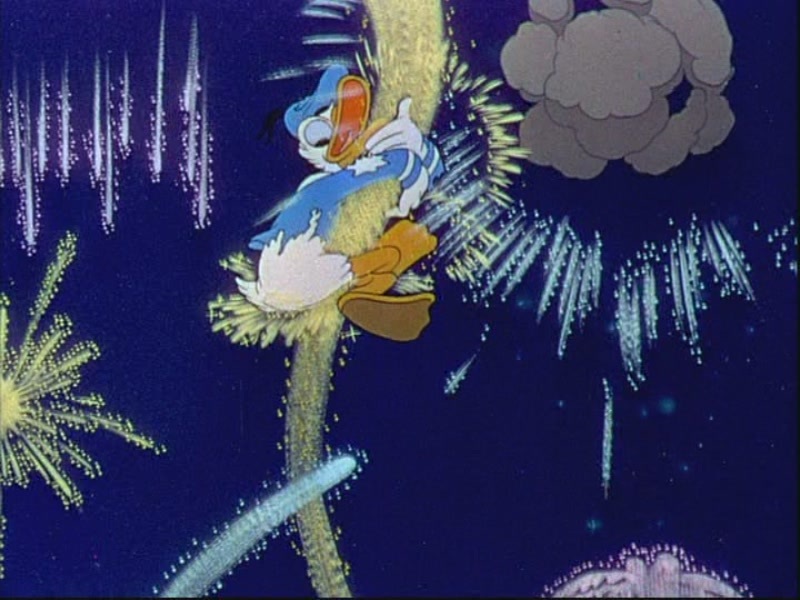

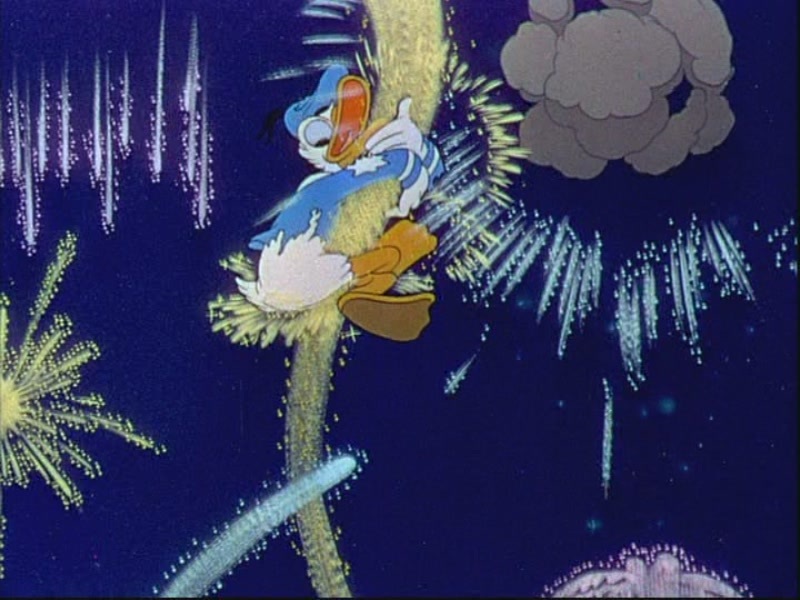

After Orson Welles tried to implement Nelson Rockefeller’s

Good Neighbor policy with South America

in an unfinished episodic film, It’s All True (1942),

scandalizing both RKO and Latin American dignitaries

by focusing on poor and nonwhite characters,

Walt Disney dutifully offered a more conventionally

touristic and clearly segregated view of the

Continent, and succeeded spectacularly with the

same studio and many of the same dignitaries (as well

as with general audiences in both the U.S. and South

America) by offering this kitschy and visually extravagant

episodic, 70-minute film (1945), his first feature

to combine animation with live action. The title

pals are the infantile Donald Duck playing an American

tourist and the somewhat older Brazilian parrot

Joe Carioca and Mexican rooster Panchito, the latter

two playing Donald’s principal tour guides. The film

begins somewhat conventionally with tales about

Pablo, a South Pole penguin longing for warmer surroundings

who sails up the coast of Chile and Peru,

and a Uruguay boy gaucho who enters a flying donkey

in a race. Read more

This appeared in the November 15, 1991 issue of the Chicago Reader. — J.R.

VIDEOS BY SADIE BENNING

“I would like to call this new age of cinema the age of the caméra-stylo [camera-pen],” Alexandre Astruc wrote prophetically in 1948 in the journal Écran français. “This metaphor has a very precise sense. By it I mean that the cinema will gradually break free from the tyranny of what is visual, from the image for its own sake, from the immediate and concrete demands of the narrative, to become a means of writing just as flexible and as subtle as written language . . .

“It must be understood that up to now the cinema has been nothing more than a show. This is due to the basic fact that all films are projected in an auditorium. But with the development of 16-millimeter and television, the day is not far off when everyone will possess a projector, will go to the local bookstore and hire films written on any subject, of any form, from literary criticism and novels to mathematics, history, and general science. From that moment on, it will no longer be possible to speak of the cinema. Read more

I wouldn’t call this a masterpiece, but it’s certainly honorable and original. I suspect that a major reason why Ari Folman’s animated nightmare has been picking up some sizable awards–best picture by the National Society of Film Critics, best foreign-language film at the Golden Globes–is that it does something that the mainstream U.S. news media more or less refuses to do. It allows the American public to express its disgust and horror for what’s currently happening in Gaza. In a similar way, albeit far more indirectly, roughly two year ago, Clint Eastwood’s Letters from Iwo Jima allowed many of us to cope a little better with some of our rage and sorrow about the occupation of Iraq. And as I noted at the time in my capsule review for that film, Waltz with Bashir also suggests that distinguishing between meaningful and senseless wars may be a civilian luxury. [1/12/09] Read more

From the Chicago Reader (June 23, 2006). — J.R.

Three Times

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Hou Hsiao-hsien

Written by Chu T’ien-wen and Hou

With Chang Chen, Shu Qi, Di Mei, Liao Su-jen, and Mei Fang

For decades Chinese history has been suppressed in China, on the mainland and in Taiwan, whether the subject is occupation or revolution, communism or capitalism. Recovering that history has become an obsession for art film directors such as Hou Hsiao-hsien, Jia Zhang-ke, Stanley Kwan, Edward Yang, Tian Zhuangzhuang, Tsai Ming-liang, and Wong Kar-wai, whose films are set in both the past and the present.

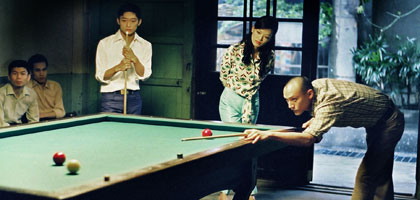

Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Three Times (2005) is split into three episodes set in Taiwan, each running about 40 minutes and featuring Chang Chen and Shu Qi; all three reflect Hou’s overriding concern with the way one’s sense of freedom, desire, and life possibilities is inflected by the age one lives in. The episodes are also about romantic disconnection and failed communication, with the romantic tensions reflecting international ones.

In “A Time for Love,” set in 1966 in Kaohsiung, Chen (Chang) receives his draft notice, then writes a love letter to May (Shu), who works at the snooker parlor where he hangs out. He discovers that she’s taken a job at another snooker parlor, and to the strains of “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes” and “Rain and Tears” he heads off to find her before reporting for duty. Read more

Early in 2009, I received a phone call from Béla Tarr, asking me if I could write a page about Sátántangó (1994) for a Hungarian newspaper to celebrate its 15th anniversary. Here’s what I sent him. —J.R.

Sátántangó at 15

Congratulations to Sátántangó on its 15th anniversary. Now that it’s a teenager, I’m happy that English-speaking fans can finally, at long last, look forward to an English translation of László Krasznahorkai’s novel. As a member of PEN, I was invited last year to suggest literary works for English translation. After I proposed Sátántangó and they published my response, I received a note from Barbara Epler of New Directions: “We are waiting on the delivery of its translation by the great George Szirtes, eagerly waiting, and will publish it as soon as we can. (We already have his translations of László’s The Melancholy of Resistance and War & War.)” So once it appears, I’ll no longer have to depend on the French translation by Joëlle Dufeuilly (2000) published by Gallimard, which I’ve owned for many years.

The film finally became available here last year on DVD from Facets Video, helping to demonstrate how much cinema as a “language” is more easily translatable than literature. Read more

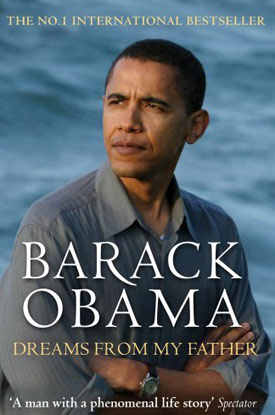

DREAMS FROM MY FATHER: A STORY OF RACE AND INHERITANCE by Barack Obama (New York: Three Rivers Press) 1995, 480 pp.

This book, which I’m still reading (I’m in its final section, about Kenya), is considerably more powerful, both as writing and as autobiography, than Obama’s follow-up book, The Audacity of Hope: Thoughts on Reclaiming the American Dream. For me the most striking episode so far occurs in New York, and, significantly enough, it occurs at the movies. (Most of the gist of this episode can be found on pp. 123-125, towards the end of the first of the book’s three main sections, “Origins”.)

During a visit from Obama’s (white) mother, she finds an ad for a downtown revival of Black Orpheus in the Village Voice, which she describes as the first foreign film she ever saw, when she was 16 and in Chicago and “thought it was the most beautiful thing I’d ever seen.” She and Obama and his sister Maya go to the revival house in a cab (the cab is a typically telling novelistic detail), and halfway through the picture Obama finds himself seething at what he finds racist and paternalistic in this white, French depiction of black and brown Brazilians in the Rio favelas during Carnival — which he describes as “the reverse image of Conrad’s dark savages” [in Heart of Darkness]. Read more

This is one of a series of essays that I wrote in 2007 about four Fassbinder films for Madman, the Australian DVD label. The other three — on Martha, Katzelmacher, and The Bitter Tea of Petra von Kant — can be found elsewhere on this site. —J.R.

I’m still trying to figure out what I think of Rainer Werner Fassbinder (1945-1982). An awesomely prolific filmmaker (he turned out seven features in 1970 alone), he became the height of Euro-American fashion during the mid-70s, then went into nearly total eclipse after his death from a drug overdose –- reminding us that the fates of the fashionable can often be precarious.

Openly bisexual, tyrannical on his sets, and habitually dressed in a leather jacket, Fassbinder cut a starlike figure in the firmament of New German Cinema, though he was hardly alone. If the French New Wave of the 60s was mainly about films, the New German Cinema of the 70s was mainly about filmmakers, and each of the best-known directors had a claim to fame that was mainly a matter of public image: eccentric exhibitionism crossed with German romanticism (Werner Herzog), existentialist hip crossed with black attire and rock ‘n’ roll (Wim Wenders), Wagnerian pronouncements (Hans-Jürgen Syberberg), a dandy’s stupefied worship of shrines and divas (Werner Schroeter), and so on. Read more

This appeared in the Chicago Reader‘s February 3, 2006 issue. Tommy Lee Jones’ subsequent feature, The Homesman, confirms the talent, originality, and boldness of Jones as a director, even if it may also come across at certain junctures as less lucid than its predecessor. — J.R.

The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Tommy Lee Jones

Written bu Guillermo Arriaga

With Jones, Barry Pepper, Julio Cesar Cedillo, Dwight Yoakam, January Jones, and Melissa Leo

At last year’s Cannes film festival, The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada walked off with the prizes for best actor (Tommy Lee Jones) and best screenplay (Guillermo Arriaga). It’s often hard to disentangle story, acting, and direction when they’re working together as well as they are here, but I would have honored Jones for his direction. That prize went to Michael Haneke for Caché, his eighth theatrical feature. This is Jones’s first, though he directed (and cowrote and starred in) a made-for-TV western, the 1995 The Good Old Boys.

Both Haneke’s and Jones’s films are political. The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada, a western, protests the abusive treatment of Mexican immigrants in west Texas, and Caché, an anxiety-ridden crime thriller, protests the abusive treatment of Algerians in France. Read more

Cinema. Film Study. What a pity that the left hand rarely knows what the right hand is doing, and vice versa.

Thanks to the generosity of Girish Shambu, I’m the happy owner of a copy of Timothy Barnard’s retranslated, reselected, and annotated edition of André Bazin’s What is Cinema?, recently published in a handsome hardcover by www.caboosebooks.com, based in Montreal, with Varvara Stepanova’s 1922 woodcut of Charlie Chaplin, Sharlo Takes a Bow, gracing the cover.

First, here is the selection: “Ontology of the Photographic Image,” “The Myth of Total Cinema,” “On Jean Painlevé” (a short fragment that Barnard has translated for the first time), “An Introduction to the Charlie Chaplin Persona,” “Monsieur Hulot and Time,” “William Wyler, the Jansenist of Mise en Scène,” “Editing Prohibited,” “The Evolution of Film Language,” “For an Impure Cinema: In Defense of Adaptation,” “Diary of a Country Priest and the Robert Bresson Style,” “Theatre and Film (1),” “Theatre and Film (2),” and “Cinematic Realism and the Italian School of the Liberation”.

Regrettably, the 354-page book, with a ten-page Publisher’s Foreword, the aforementioned 13 essays by Bazin, 61 pages of helpful annotation, a combined 19-page Glossary of Films and Film Title Index, and a six-page Index of Names, is unavailable to most people outside of Canada, and for legal reasons, including copyright laws, you can’t even order this from Canadian Amazon. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (February 21, 1997). It’s worth noting that Japanese doesn’t distinguish between singular and plural, so that the film is also known as The Story of the Last Chrysanthemum, which is an equally accurate translation. — J. R.

Though not the best known of Kenji Mizoguchi’s period masterpieces, this 1939 feature is conceivably the greatest. (For me the only other contender is Sansho the Bailiff.) The plot, which oddly resembles that of There’s No Business Like Show Business, concerns the rebellious son of a theatrical family devoted to Kabuki who leaves home for many years, perfects his art, aided by a working-class woman who loves him, and eventually returns. Apart from the highly charged and adroitly edited Kabuki sequences, the film is mainly constructed in extremely long takes, and an intricate rhyme structure between two time periods is developed by matching camera angles in the same locations. Never before or since (apart from The 47 Ronin) has Mizoguchi’s refusal to use close-ups been more telling, and the theme of female sacrifice that informs most of his major works is given a singular resonance and complexity here. Demonstrating an uncanny mastery of framing and camera movement, the film also has a complexity of characterization that’s shown with sublime economy. Read more

I’m sorry that the Chicago Reader in its current issue chooses not to acknowledge that it’s anything special or worthy of more than cursory notice, but Edward Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day is probably the greatest Taiwanese film ever made, and it doesn’t turn up here often. Doc Films is showing it at 7 pm. Here’s my original capsule review, only slightly updated:

Bearing in mind Theodore Dreiser’s An American Tragedy, this astonishing 230-minute epic (1991) by Edward Yang (1947-2007), set over one Taipei school year in the early 60s, would fully warrant the subtitle “A Taiwanese Tragedy.” A powerful statement from Yang’s generation about what it means to be Taiwanese, superior even to his later masterpiece (and final film) Yi Yi (2000), it has a novelistic richness of character, setting, and milieu unmatched by any other 90s film (a richness only partially apparent in its three-hour version). What Yang does with objects — a flashlight, a radio, a tape recorder, a Japanese sword — resonates more deeply than what most directors do with characters, because along with an uncommon understanding of and sympathy for teenagers Yang has an exquisite eye for the troubled universe they inhabit. This is a film about alienated identities in a country undergoing a profound existential crisis — a Rebel Without a Cause with much of the same nocturnal lyricism and cosmic despair. Read more

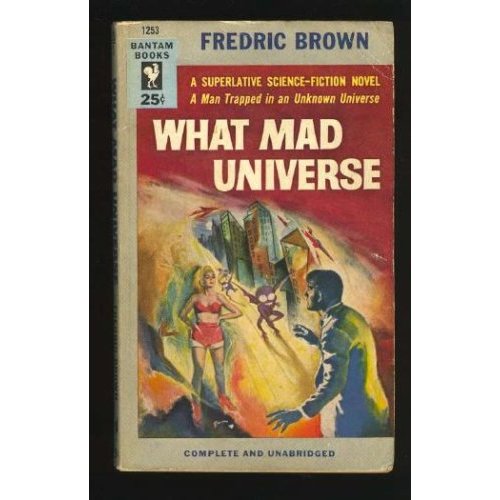

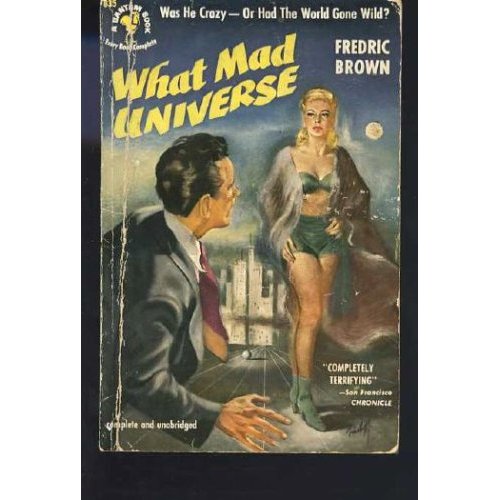

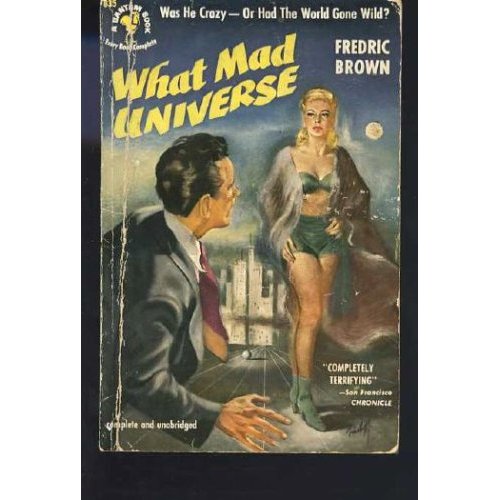

One of my favorite writers since childhood has been the prolific Fredric Brown (1906-1972), both for his mysteries and his science fiction. The former is much more plentiful than the latter—so much so that it’s been possible in recent years to publish practically all his science fiction in two thick hardcover volumes, From These Ashes (the short stories, 690 pages) and Martians and Madness (the novels, 633 pages). (The “madness” in the latter title partially relates to What Mad Universe, Brown’s best SF novel, as well as one of his very best SF stories, “Come and Go Mad”, although it also qualifies as an ongoing Brown theme in some of the mystery plots as well.)

On the other hand, it might take an AIG bonus to pay for all of Brown’s out-of-print mystery, crime, and detective fiction; some of the 19 or so limited-run paperback collections devoted to the stories that were published in the 80s and 90s now sell on the Internet for close to a thousand bucks apiece, and a few of the novels are comparably pricey.

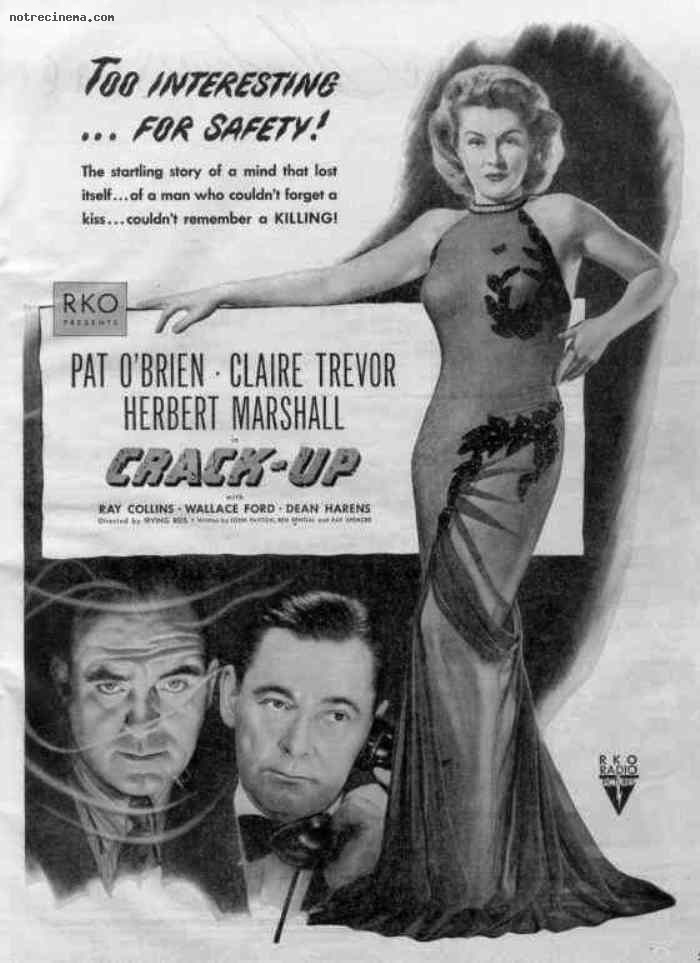

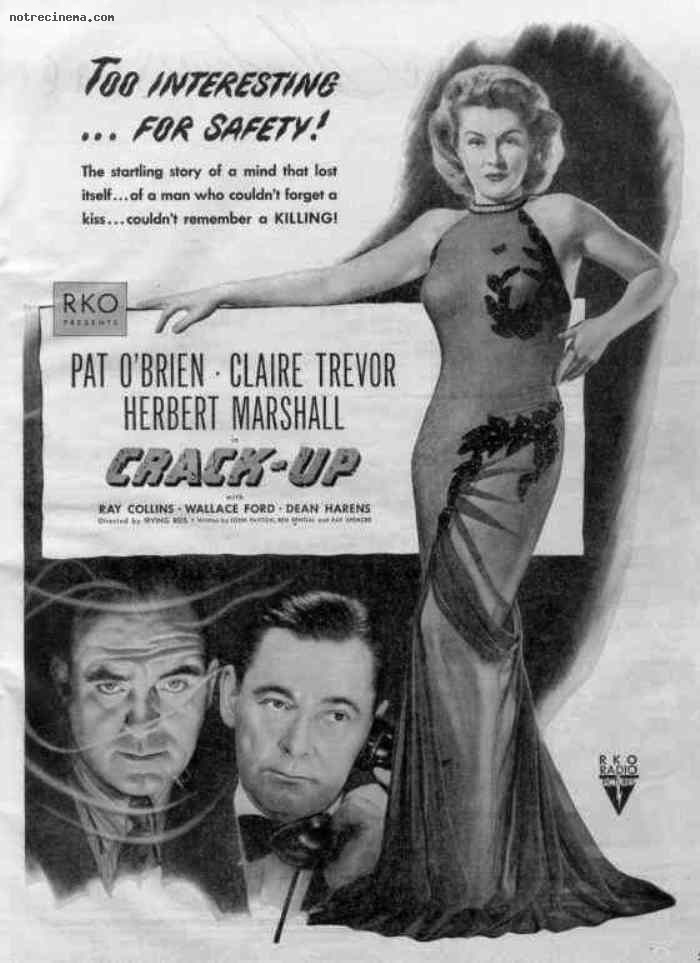

Probably the two best known Hollywood features derived from Brown mysteries are Screaming Mimi (Gerd Oswald, 1958) and Crack-Up (Irving Reis, 1946)—the latter derived from a 1943 Brown novella called “Madman’s Holiday” that’s now available only in one of those limited-run paperbacks that currently sells for $995 and $950 on Amazon, hideous jacket (see below) and all. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (June 8, 2007) — J.R.

PRIVATE FEARS IN PUBLIC PLACES ****

DIRECTED BY ALAIN RESNAIS | WRITTEN BY JEAN-MICHEL RIBES AND ALAN AYCKBOURN

WITH SABINE AZEMA, ISABELLE CARRE, LAURA MORANTE, PIERRE ARDITI, ANDRE DUSSOLLIER, AND LAMBERT WILSON

It might sound crazy to call Alain Resnais the last of the great Hollywood studio directors when he’s never made a single movie in Hollywood. But classic Hollywood filmmaking, as defined by the aesthetics and craftsmanship of the system from the 30s through the 60s, transcends location. Indeed, many of the best recent examples, like Black Book and Angel-A, are European. And from its breathtaking opening shot, which sweeps across a wintry Parisian cityscape to the windows of an apartment house just as blinds are lowered and a door slams, the director’s newest film, Private Fears in Public Places, clearly belongs to that tradition.

Made by Resnais in his mid-80s, this movie is a real heart-breaker—one reason I prefer the French title, Coeurs (“hearts”). Derived from a recent play by Alan Ayckbourn (Resnais also adapted his Intimate Exchanges for the 1993 film Smoking/No Smoking), Private Fears in Public Places is a labyrinthine tale of crisscrossing destinies, missed connections, enclosures that poignantly echo one another, and muffled romantic and erotic feelings. Read more

This review appeared originally in Fanzine, 6/26/08. –J.R.

Given the size of his achievement, it’s astonishing that Jacques Tati made only half a dozen features, none of them bad. But if I had to single out any of these as a lesser work, I’d pick Trafic (1971), the only one that qualifies as compromised.

Others might select Parade (1973), Tati’s final film –– because it was mainly shot on video and virtually dispenses with plot by basically following the contours of a far-from-spectacular circus performance. But they’d be wrong. Though it’s the least known Tati feature and the most modest in terms of budget, Parade is by no means Tati’s least ambitious or adventurous film. In some ways it even qualifies as his most radical –– in its refusal to clearly separate life from spectacle or prioritize professional performers over unprofessional spectators. Unfortunately, the less analytical and more sentimental celebrations of Tati –– including the charming 1989 documentary by the late Sophie Tatischeff about her father, In the Footsteps of Monsieur Hulot, that’s a bonus on the second disc here –– tend to overlook this radicalism.

Trafic, on the other hand, represented a conscious step backward for Tati. Read more