From the Chicago Reader (November 22, 1991). — J.R.

CAPE FEAR

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed by Martin Scorsese

Written by Wesley Strick

With Robert De Niro, Nick Nolte, Jessica Lange, Juliette Lewis, Joe Don Baker, Illeana Douglas, Fred Dalton Thompson, and Robert Mitchum.

I have nothing against pornography when it’s good, clean sex, but I don’t enjoy watching a cat play with a mouse, and I got no pleasure from seeing Mr. Mitchum — huge, brawny and sweatily bare-chested — toy first with the frantically terrified ten-year-old daughter and then move on to conquer her shrinking, pleading mother. — Dwight Macdonald

Cape Fear is heavy on Spanish moss and sick behavior, a classic demonstration of the differences between rich and poor; to say nothing of the typical good ol’ Southern boy’s view of women. Unfortunately, there aren’t many of ’em have very much good to say. You won’t forget this movie, especially if you’re a Yankee Jew. — Barry Gifford

These remarks come from reviews of the original Cape Fear. Macdonald’s was written the same year the movie came out, 1962, and Gifford’s a couple of decades later; together, they help to show how we’ve increasingly come to view nastiness as a form of high art. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 1, 1989). — J.R.

Also known as Memory of Appearances, this ambitious feature by the extraordinary and prolific Raul Ruiz relocates portions of both versions of Calderon’s Life Is a Dream — the sacred and profane versions, written many decades apart — in a provincial movie theater, where a Chilean revolutionary tries to recall portions of a secret code drawn from the text, gets interrogated by the police behind the movie screen, and imagines himself as a participant in some of the genre films he’s watching. If this sounds confusing, it’s nothing compared to the multileveled games with the imagination that Ruiz plays throughout this intriguing labyrinth, where vestiges of science fiction, musical comedy, western shoot-outs, and costume dramas rub shoulders with themes and lines from Calderon. The important thing to keep in mind is that, however murky the proceedings may get, Ruiz is basically out to have fun, and as one of the supreme visual stylists in the contemporary cinema, he can guarantee more visual surprises and bold poetic conceits than we are likely to find crowded together elsewhere. Cheerfully indifferent to the modernist notion of a masterpiece, he conflates the profound with the tacky in a liberating manner that turns both into a witty carnival of attractions (1986). Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 14, 1989). — J.R.

HENRY: PORTRAIT OF A SERIAL KILLER

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by John McNaughton

Written by Richard Fire and McNaughton

With Michael Rooker, Tracy Arnold, and Tom Towles.

Properly speaking, the slasher movie made its debut almost 30 years ago, with two features by middle-aged Englishmen, which coincidentally opened on separate continents within a few months of each other — Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom, which premiered in England in May 1960, and Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, which opened in the United States three months later. The parallels between these two movies remain striking — especially their puritanical and voyeuristic underpinnings, which give us sexually repressed heroes whose morbid scopophilia (pleasure in gazing) leads directly to their brutal murders of women. And both occasioned critical protests of rage and disapproval when they first appeared.

But it was Psycho and not Peeping Tom that went on to launch a subgenre and receive exhaustive (and exhausting) analysis. And from the vantage point of the present, it is probably the shower murder of Psycho rather than the Odessa Steps sequence of Potemkin that has become the most chewed-over montage sequence in the history of cinema. But how much concrete edification has grown out of this close study? Read more

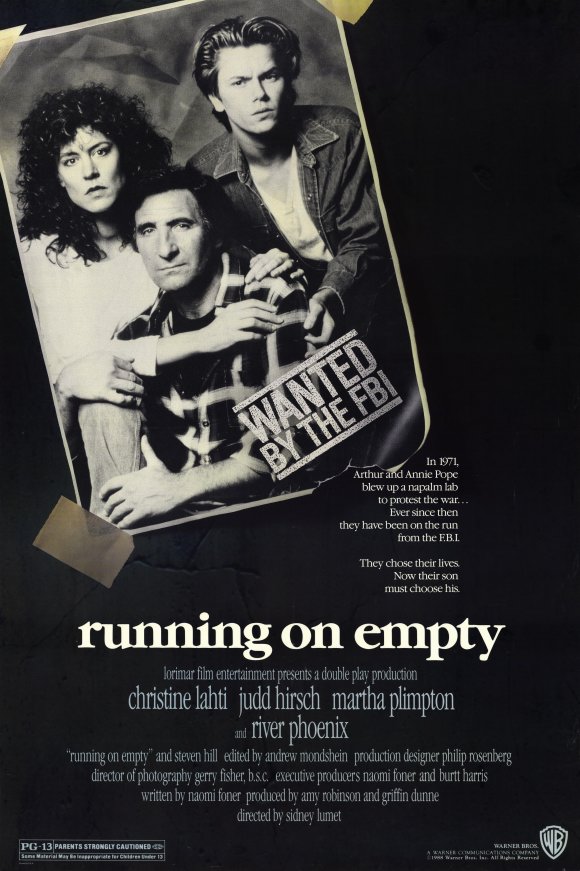

From the Chicago Reader (October 11, 1988). — J.R.

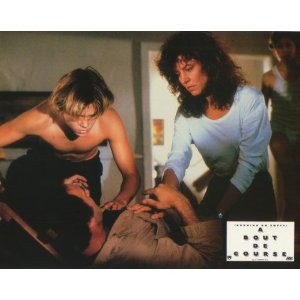

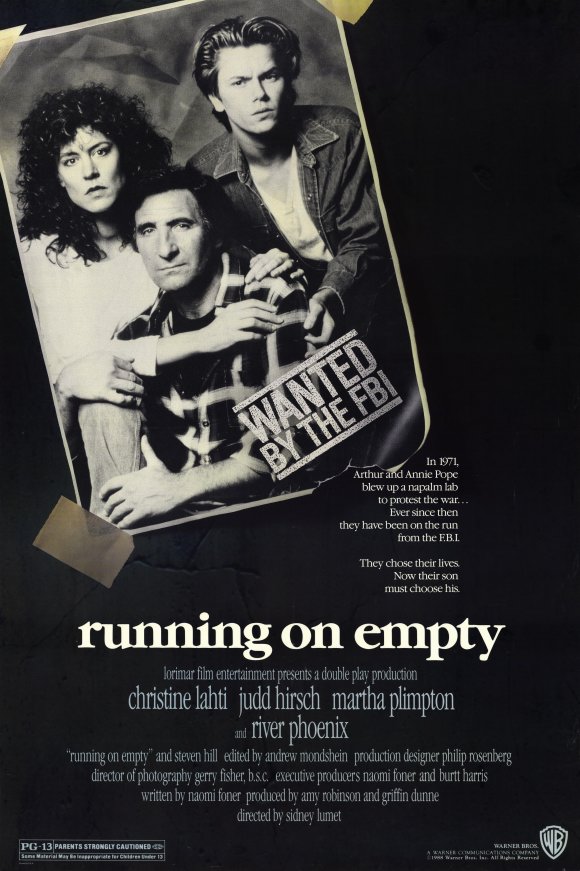

RUNNING ON EMPTY

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Sidney Lumet

Written by Naomi Foner

With Christine Lahti, River Phoenix, Judd Hirsch, Martha Plimpton, Jonas Abry, Ed Crowley, and Steven Hill.

It’s a truism that the distant past is easier to see clearly than the more recent past, so it shouldn’t be too surprising that current movie depictions of the 40s and 50s — Tucker, to name just one — tend to be more accurate, at least about the dreams and fantasies of those periods, than movies about the 60s and 70s. Paul Schrader’s recently departed Patty Hearst offers a salient case in point: it can only broach the early 70s through a sitcom or comic-book reduction of the way that radicals talk and think — a myopic 80s reading of the period that leaves a number of gaps in the picture. Schrader fills in some of these gaps by clever employments of style and attitude, the stock-in-trade of any current music video, but in the end one huge gap remains: Who was Patty Hearst? What was the Symbionese Liberation Army? Why should anyone be concerned with them? The attention-getting nowness of the film blots out any possibility for history or social observation; just as Schrader’s earlier Mishima seemed to have more to do with Las Vegas than with any reading of Japanese history or culture, his take here on 60s/70s radicalism seems mired exclusively in the preoccupations of the present. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 1, 1988). — J.R.

Except for The Red Shoes, this shot-by-shot rethinking of a dance performance by the Emile Dubois Dance Group, choreographed by Jean-Claude Gallotta and directed by Raul Ruiz, could be the greatest dance film ever made. Running only 65 minutes, the 1986 film is as much a sensual workout as Ruiz’s Life Is a Dream is an intellectual one; its celebration of pure physicality and movement is as exciting for film lovers as it is for dance enthusiasts. Using a Welles-inspired cinematography of wide angles, deep focus, shadows, silhouettes, and tilted perspectives, Ruiz and his gifted cameraman, Acacio de Almeida, join the spirited group of nine dancers not as detached observers or as competitors but as collaborators in the deepest sense of the word. Working through a continually mutable stage decor until the performance reaches a grand climax in the open air, by the sea, the film is almost as arresting aurally as it is visually, thanks to its natural sounds, music, and nonverbal utterances, all of which are superbly integrated with the physical movements. An exhilarating masterpiece, and in many respects Ruiz’s most accessible work of the 80s. (JR)

Read more

Read more

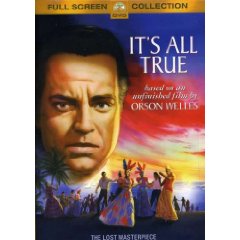

From my 2007 collection Discovering Orson Welles and the Chicago Reader (October 29, 1993). -– J.R.

I’m one of the people who receives an acknowledgment in the final credits of It’s All True: Based on an Unfinished Film by Orson Welles, but in fact I regret the contribution I made to this film. During a phone conversation with Bill Krohn, one of the writers, directors, and producers, Bill told me that one of the French producers, Jean-Luc Ormières, was looking desperately for a composer for the documentary who wouldn’t charge too much money. I suggested Jorge Arriagada — the Chilean film composer who at that point had written the scores for something like a couple of dozen films by Râúl Ruiz, a filmmaker I greatly admire as well as a friend — and Arriagada wound up getting hired for the job. I recall having heard that Arriagada mainly worked for Ruiz because he liked to do so rather than out of economic necessity, and this fact combined with Ruiz’s own Welles worship and Arriagada’s South American background made him seem ideal. Unfortunately, this conclusion was built on the common Anglo-American fallacy that Latin America is something like a single homogeneous culture — the same assumption, I presume, that years later would prompt Colin MacCabe, the producer at the British Film Institute of a series of national film histories on film or video assigned to various filmmakers, to assign the whole of Latin American cinema to one (admittedly very talented and knowledgeable) Brazilian director, Nelson Pereira dos Santos, yielding his 93-minute Cinema of Tears in 1995. Read more

The third and most enjoyable of Gilbert Adair’s Evadne Mount mysteries, just published in the U.K., is by all counts the least satisfying or conventional as a mystery—even though Adair, who features himself as first-person narrator, largely compensates for this by shoe-horning in a rather brilliant pastiche of a Sherlock Holmes tale in the fourth chapter, roughly a third of the way through.

Adair is a master of pastiche whose best-known previous novels (and even one of his non-fiction books, Myths and Memories) all derive from literary models, so that Alice Through the Needle’s Eye is a brilliant Lewis Carroll spinoff, The Key of the Tower is an hommage to Alfred Hitchcock, and even his two best-known books, both made into films, The Dreamers (known in an earlier version as The Holy Innocents) and Love and Death on Long Island, are derived respectively from Jean Cocteau’s Les Enfants Terribles and Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice. The Evadne Mount novels, the first two of which are The Act of Roger Murgatroyd and A Mysterious Affair of Style, are all to varying degrees nods to Agatha Christie, to whom the latest is dedicated, but the postmodernist tricks and games with form, genre, and language tend to overtake the mystery elements—especially in the third, which gradually evolves into a rather merciless and scathing autocritique by Adair of his own literary narcissism as voiced by lady detective Mount, his own creation. Read more

A chapter from my book Film: The Front Line 1983 (Arden Press, 1983), still in print. — J.R.

Jacques Pierre Louis Rivette

Born in Rouen, France, 1928

Perhaps no single figure in this survey dramatizes the contradictions of the avant-garde film as an institution and social force better than Jacques Rivette — a major filmmaker who has consistently been denied credentials, recognition, or any sort of protection by the “official” avant-garde establishment, even though his work has generally been shunned just as consistently by the mainstream power structures. Who, then, gives a damn about Jacques Rivette? More people than either establishment cares to acknowledge or deal with. As someone who has written a good deal about Rivette, programmed his films in three countries, and edited the only book devoted to him in English (or French), I can report that everywhere I go, I meet passionate Rivette fanatics.

In London, I once met an American who dutifully translated most of Rivette’s old Cahiers du Cinéma reviews in his spare time, simply for his own amusement. I also once shared a Hampstead maisonette with a brilliant Israeli-born lecturer in philosophy of art whom I took to a screening of the four-hour Out 1: Spectre; he spent most of the rest of the night telling me why it was the greatest film ever made — only a sleepless day or so before he temporarily flipped his lid and tried to chop down part of our kitchen wall with a hatchet. Read more

From Film Comment (Spring 1972). — J.R.

According to the current issue of Pariscope – an indispensable guide to local moviegoing 260 films will have public screenings in Paris this week: 217 at commercial theaters, and 43 at the two Cinémathèques. By rough count, only 67 of these (about one fourth) are French. A hundred more are American, and the remaining 93 are split between fifteen other nationalities. Of the non-French films, approximately 40% are subtitled; except for a dozen or so at the Cinémathèques that will be shown without translation, the rest are dubbed.

It is possible that New York is beginning to surpass Paris in the number of interesting films that one can see. Yet the paradox remains that, if one excludes television – an incomplete form of film-watching at best – Paris maintains a decisive edge in narrative American cinema. To list only a dozen of the current undubbed features, is there anywhere else in the world where one can see ANATOMY OF A MURDER, ALL ABOUT EVE, DUCK SOUP, EASTER PARADE, MODERN TIMES, SALLY OF THE SAWDUST, THE SALVATION HUNTERS, SCARFACE, STAGECOACH, THE STRONG MAN, TABU, and THE WEDDING MARCH in a single week?

Aside from this particular kind of richness, there are pleasures, courtesies, and conveniences – as well as a few irritations – involved with Parisian moviegoing that one takes for granted here, but would not expect to find in the states. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 15, 1996). — J.R.

Deseret

Directed and written byJames Benning

Narrated by Fred Gardner.

Andre Gide’s The Counterfeiters is too tremendous a thing for praises. To say of it “Here is a magnificent novel” is rather like gazing into the Grand Canyon and remarking, “Well, well, well; quite a slice.”

Doubtless you have heard that this book is not pleasant. Neither is the Atlantic Ocean. — Dorothy Parker

One of the main characteristics of experimental films is that they tend to make hash of the terms we use to speak about narrative features, and James Benning’s haunting, beautiful, and awesome Deseret (1995) — his eighth feature-length film — performs this valuable function from the outset. To say that Deseret is “directed” and “written” by Benning requires some bending of the categories. He “directed” it insofar as he conceived the project, filmed the images, recorded the sound, and edited the sound and images; he “wrote” it insofar as he compiled and edited the texts that are read offscreen by Fred Gardner, though he didn’t write them. In a Hollywood film the directorial tasks described above would be carried out by a producer, cinematographer, sound recordist, editor, and sound editor; it’s anybody’s guess what the compiler and editor of the text would be called (researcher? Read more

My interview with Alain Resnais in New York in December 1980 yielded three separate articles, written for Soho News, American Film, and Omni. This is an unedited draft of the latter; I can’t recall now whether or not it was ever published in some form, but I think it probably wasn’t. -– J.R.

From the 42nd floor of Manhattan’s elegant Park Lane Hotel, where French director Alain Resnais has been holding court, Central Park in the winter looks remote and unfamiliar, like the terrain of another planet. It resembles Resnais’ unexpected smash hit Mon Oncle d’Amérique -– a unique, original blend of art and science –- by resisting precise description almost as confidently as it invites contemplation and wonder. And if the angle of vision that helps to account for this strangeness faintly suggests the vantage point of an amused yet saturnine deity, gazing down almost nostalgically, something of the same ambiance seems to inform the relation of the 58-year-old Resnais to his haunting comedy.

A master director who’s also a master of indirection -– always electing to tell a story in a different offbeat manner -– Resnais has never scripted any of his own features, But all of them are unmistakably personal reflections, generally about the past. Read more

From Video Times (February 1985). — J.R.

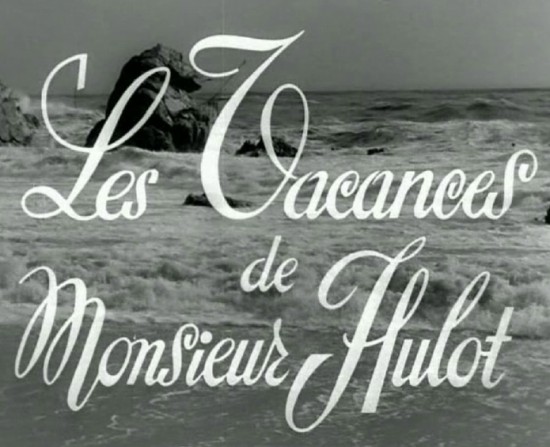

Mr. Hulot’s Holiday

(1953), B/W, Director: Jacques Tati. With Jacques Tati, Nathalie Pascaud, André Dubois, and Michelle Rolla. 96 min. Embassy, $59.95

Popular films that are also works of art are rare gems, and Mr. Hulot’s Holiday remains one of the artistic jewels in movie comedy. It is as great in its way as the best of Chaplin and Keaton. A radically different way of experiencing the world. it is such an unpretentious movie that it initially comes across as anything but radical. Even the set of instructions at the opening of the film are so laid-back and unassuming that they are hardly instructions at all: “Mr. Hulot is off for a week by the sea…Spend it with him…Don’t look for a plot, for holiday is meant purely for fun…If you look for it, you will find more fun in ordinary life than in fiction…So relax and enjoy yourselves…See how many people you can recognize. You might even recognize yourself.”

The preceding appears over waves crashing against the shore; director Jacques Tati, who also plays the title hero, Monsieur Hulot, then cuts to a shot of an abandoned boat on the beach. He holds on the boat until another succession of waves come in, then cuts to a crowded, noisy railroad station in France at the peak of the summer season. Read more

From American Film (December 1979). I’ve trimmed this a bit. — J.R.

“Production alternatives, linguistic and symbolic mutations, new models of the entertainment spectacle, new forms of film consumption, the relation between various media, the financial state of various film industries…”

In the words of an introductory brochure, these were some of the topics and problems to be explored at an international conference, “Cinema in the 80s,” set in the midst of the Venice Biennale. For the thirty-odd speakers, myself included, who had been flown all the way to the Palazzo del Cinema on the Lido, there was plenty to think about while overcoming jet lag.

The conference’s three days were devoted to language, industry, and audience, in that order. Simultaneous translation (of a sort) over earphones offered versions of each speech in Italian, French, English, German, and Spanish. Despite these noble efforts, the conference inevitably evoked a Tower of Babel at times. Bringing together academics, critics, and filmmakers from half a dozen countries, thre sessions helped to clarify how far most members of each profession are today from speaking a common tongue. Specialists and experts on their elected turfs, they often respond like fish out of water when confronted with film people of different sorts. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (December 29, 1997). To tell the the truth, almost 27 years later, I’m a little embarrassed about having given this movie four stars. For all my affection for James L. Brooks, in spite of everything (and including his most recent picture, the much-reviled How Do You Know), this is far from being his best work. — J.R.

As Good as It Gets **** Masterpiece

Directed by James L. Brooks

Written by Mark Andrus and Brooks

With Jack Nicholson, Helen Hunt, Greg Kinnear, Cuba Gooding Jr., Skeet Ulrich, Shirley Knight, Yeardley Smith, Lupe Ontiveros, Jesse James, and Jill.

As a TV illiterate who probably hasn’t watched a sitcom regularly since The Honeymooners, who’s never seen Taxi, Rhoda, Lou Grant, Room 222, or The Tracey Ullman Show, and caught only the final episode of The Mary Tyler Moore Show, I don’t know much about the world James L. Brooks sprang from as an artist. In fact, apart from several episodes of his two cartoon series, The Simpsons and The Critic, I don’t know his TV work at all. And as someone who regards movie test-marketing as one of the sleaziest, most destructive practices in Hollywood, I’m more than a little skeptical about a writer-director-producer who believes in it so religiously that after the previews of his previous feature, the musical I’ll Do Anything, he recut it so extensively he made it a nonmusical. Read more

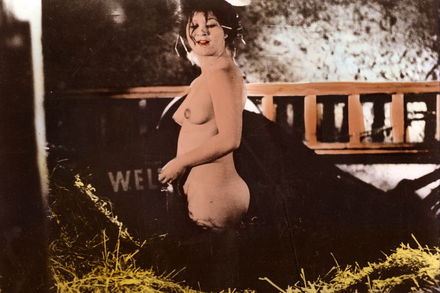

This review appeared in the January 1977 issue of Monthly Film Bulletin. The American title of this film was Jailbait.– J.R.

Wildwechsel (Wild Game)

West Germany, 1972

Director: Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Cert — X. dist –- Contemporary. p.c –- InterTel (West German TV). In collaboration with Sender Freies. p — Gerhard Freund. p. sup -– Manfred Kortowski. p. manager -– Rudolf Gürlich, Siegfried B. Glökler. asst. d –- Irm Hermann. sc –- Rainer Werner Fassbinder. Based on the play by Franz-Xaver Kroetz. ph –- Dietrich Lohmann. In colour. ed — Thea Eymèsz, a.d –- Kurt Raab, m -– excerpts from the work of Beethoven. songs -– “You Are My Destiny” by and performed by Paul Anka. l.p –- Eva Mattes (Hanni Schneider), Harry Baer (Hans Bermeier), Jörg von Liebenfels (Erwin Schneider), Ruth Drexel (Hilda Schneider), Rudolf Waldemar Brem (Dieter), Hanna Schygulla (Doctor), Kurt Raab (Factory Boss), El Hedi Ben Salem (Franz’s Friend), Karl Schedit and Klaus Michael Löwitsch (Policemen), Irm Hermann and Marquart Bohm (Police Officials). 9,180 ft. 103 min. Subtitles.

Hanni Schneider, fourteen, gets picked up by Franz Bermeier, nineteen, and loses her virginity with him in a hayloft. Read more