Trevor Vartanoff, one of the frequenters of this web site, has come up with an invaluable gift to me and to others — an alphabetical master index of all (or almost all) the postings here, complete with links. “I found it useful,” Trevor just wrote me, “maybe you or readers will too.” (2021 postscript: sorry for the links here that no longer work.) — J.R.

Featured Texts

*Corpus Callosum

*CORPUS CALLOSUM

12 Monkeys

12 and Holding

15th Annual Festival of Illinois Film and Video

2 Oxford Companion Entries (Albert Brooks and découpage)

2 or 3 Things I Know About Her

2001: A Space Odyssey

2046

20th International Tournee of Animation

29th Chicago International Film Festival: Mired in the Present

4 Little Girls

4

60s Wisdom

7 Women

8 1/2

8 Mile

84 Charlie Mopic

9 1/2 Weeks with Van Gogh

A Bankable Feast [BABETTE’S FEAST]

A Beauty and a Beast

A Bluffer’s Guide to Bela Tarr

A Breakthrough And A Throwback

A Brief History of Time

A Brighter Summer Day

A Bronx Tale

A Christmas Commodity: SCROOGED

A Cinema of Uncertainty

A Constant Forge

A Couple of Kooks [MY BEST FIEND]

A Cut Above [HENRY: PORTRAIT OF A SERIAL KILLER]

A Depth in the Family [A HISTORY OF VIOLENCE]

A Dialogue about Abbas Kiarostami’s SHIRIN

A Different Kind of Swinger [GEORGE OF THE JUNGLE]

A Different Kind of Thrill (Richet’s ASSAULT ON PRECINCT 13)

A Dry White Season

A Family Thing

A Far Off Place

A Few Eruptions in the House of Lava

A Few Things Well [A LITTLE STIFF]

A Film of the Future

A Fish Called Wanda

A Force Unto Himself [on Hou Hsiao-hsien]

A Great Day in Harlem

A History of Violence

A Home of Our Own

À la recherche de Luc Moullet: 25 Propositions

A Little Transcendence Goes a Long Way

A Lucky Day

A Major Talent [on SWEETIE]

A Man Escaped

A Midnight Clear

A Moment of Innocence

A New Leaf

A Nightmare on Elm Street 4: The Dream Master

A Page of Madness

A Perfect World

A Perversion of the Past

A Place Called Chiapas

A Place in the Pantheon: Films by Bela Tarr

A Place in the World

A Price Above Rubies

A Prophet in His Own Country [Jon Jost retrospective]

A Quirky Cowboy Classic [on THE THREE BURIALS OF MELQUIADES ESTRADA]

A Radical Idea [HALF NELSON & THIS FILM IS NOT YET RATED]

A Road Not Taken (The Films of Harun Farocki)

A Room With No View [ORPHANS]

A Russian in Hollywood [SHY PEOPLE]

A Scanner Darkly

A Short Film About Killing and A Short Film About Love

A Single Girl

A Soldier’s Daughter Never Cries

A Stylist Hits His Stride (ETERNAL SUNSHINE OF THE SPOTLESS MIND)

A Tale of Love

A Tale of Winter

A Tale of the Wind

A Tale of the Wind

A Thousand Words

A Time of Love

A Time to Lie (CROSS MY HEART)

A Time to Live and a Time to Die

A Touch of Class [GOSFORD PARK]

A Woman’s Tale

A World Apart

A Year at the Movies

A Zed and Two Noughts

A.I. Read more

Here are ten of the 40-odd short pieces I wrote for Chris Fujiwara’s excellent, 800-page volume Defining Moments in Movies (London: Cassell, 2007). — J.R.

Scene

1996 / Irma Vep – Maggie Cheung stealing Arsinée Khanjian’s jewels

France (Daica Films). Director: Olivier Assayas. Cast: Maggie Cheung, Arsinée Khanjian.

Why It’s Key: If a movie can be said to have an unconscious, here’s where this one’s secret is buried.

Costumed in a tight black latex suit, Maggie Cheung, playing herself, is in Paris to play the title role in a remake of Louis Feuillade’s 1916 crime serial, Les vampires. She also seems to be the object of the sexual fantasies of everyone working on the film —- most noticeably the director (Jean-Pierre Léaud) and the woman handling costumes (Nathalie Richard).

After what seems like a restless, sleepless evening in her hotel room, Cheung goes out into the hallway, still in her suit, stealthily climbs the stairs, and, after spying a maid delivering a tray to a room and leaving, sneaks into the room herself. Still hidden, she sees a nude woman (Khanjian, wife and lead actress of Atom Egoyan) describing her lonely boredom on the phone to someone named Fred, then glimpses the woman’s jewels in another room, which she promptly steals. Read more

From The Velvet Light Trap, spring 1996 (and reprinted in my 1997 collection Movies as Politics). Given all the screenings of Out 1 that have more recently taken place on both sides of the Atlantic, with (almost) concurrent Blu-Ray and DVD releases in France, the U.K., and the U.S., this seems like a good time to repost this article. My still lengthier reflections can be found on the Carlotta digital releases in France and the U.S. — J.R.

On the Issue of Nonreception

What connections can be found between two French serials made almost half a century apart? Aside from the fact that both of them appear on my most recent “top ten” list (1), I’m equally concerned with the issue of why such pleasurable, evocative, enduring, multifaceted, and incontestably beautiful works should remain so resolutely marginal — unseen, unavailable, and virtually written out of most film histories except for occasional guest appearances as the vaguest of reference points. The problem isn’t simply an American or an academic one; although no print of either serial exists in the United States, it can’t be said that either film has received much attention in France either — or elsewhere, for that matter. Read more

Here are ten of the 40-odd short pieces I wrote for Chris Fujiwara’s excellent, 800-page volume Defining Moments in Movies (London: Cassell, 2007). — J.R.

Scene

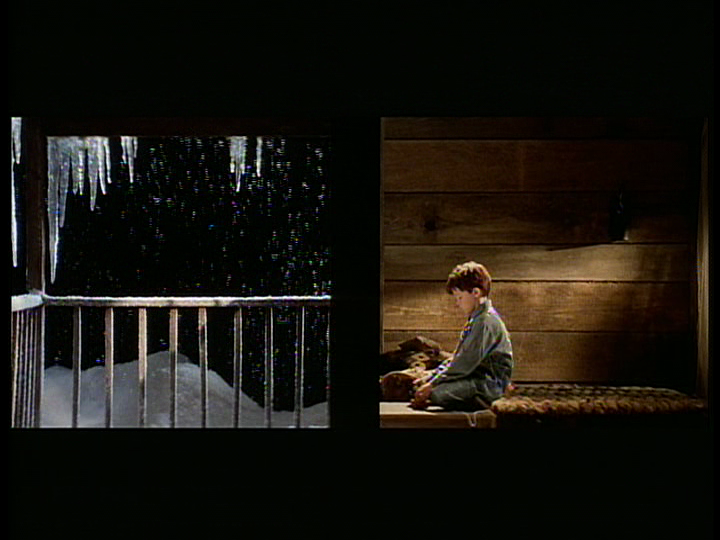

1995 / The Neon Bible – “It didn’t snow that year.”

U.K. (Academy/Channel Four). Director: Terence Davies.

Cast: Drake Bell, Jacob Tierney, Gena Rowlands.

Why It’s Key: It reveals the power of imagination in a flash.

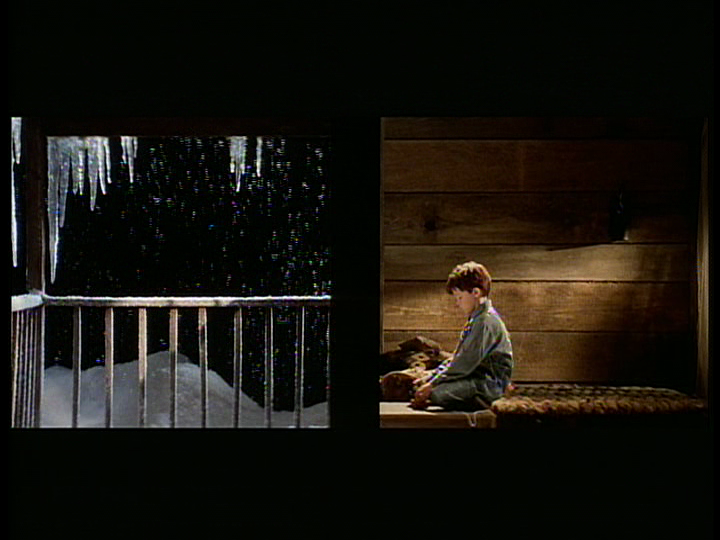

Few moments in movies reveal the power of imagination more succinctly than the opening of Terence Davies’ CinemaScope adaptation of John Kennedy Toole’s first novel, written when the southern author was only 16. It opens with 15-year-old David (Jacob Tierney) alone on a train at night, the camera moving past him to the darkness glimpsed outside. Then David at ten (Drake Bell) is seen peering out a rain-streaked window in his rural home to the strains of “Perfidia”, circa 1948, while narrating offscreen, “People came to see us that Christmas. They were nas, those people —- they brought me things…”

A moment later, we cut to a diptych: on screen left, an empty porch topped by icicles framing an enchanted snowfall, as decorous as a neatly filled box by the surrealist artist Joseph Cornell. On screen right, young David is seated on the floor inside, now looking out the same window in profile, while narrating offscreen, “There was no snow —- no, not that year.” Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 15, 1994). — J.R.

** SERIAL MOM

(Worth seeing)

Directed and written by John Waters

With Kathleen Turner, Sam Waterston, Ricki Lake, Matthew Lillard, Scott Wesley Morgan, Walt MacPherson, Justin Whalin, Patricia Hearst, and Suzanne Somers.

“Outside it’s hot and muggy. I buy a carton of cigarettes, ever bitter that I’m taxed so highly (11) on the one purchase that actually brings me happiness. They ought to tax yogurt (12); that’s what causes cancer. A neighbor, who always seems too familiar for her own good, passes me and makes the mistake of saying, ‘Good morning.’ ‘Shut up!’ I snap, making a mental note of her hideous tube top (13) and ridiculous Farrah Fawcett hairdo (14), so popular with fashion violators. And then I see it, a goddam ticket on my car, even though the meter (15) has only been in effect ten minutes. I have to take my rage out on someone! I run toward this fashion scofflaw as she gets into the most offensive vehicle known to man, “Le Car’ (16), and yank her door open as she frantically tries to lock it. ‘Not so fast, miss,’ I bark. ‘There’s a certain matter of this ticket you’ll have to take care of — $16 for gross and willful fashion violations!’ Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin , vol. 44, no. 516, January 1977.

I’ve always been somewhat skeptical about Herzog’s reputation and constructed myth as a mad genius. Here are my capsule reviews for the Chicago Reader of Lessons of Darkness (1992) and My Best Fiend (1999), respectively (on other occasions, I’ve sometimes been more supportive of his work):

In his characteristically dreamy Young Werther fashion, Werner Herzog generates a lot of bombastic and beautiful documentary footage out of the post-Gulf war oil fires and other forms of devastation in Kuwait, gilds his own high-flown rhetoric by falsely ascribing it to Pascal, and in general treats war as abstractly as CNN, but with classical music on the soundtrack to make sure we know it’s art. This 1992 documentary may be the closest contemporary equivalent to Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will, both aesthetically and morally; I found it disgusting, but if you’re able to forget about humanity as readily as Herzog there are loads of pretty pictures to contemplate. 54 min.

Werner Herzog’s surprisingly slim and relatively impersonal 1999 feature charts his relationship with the mad actor Klaus Kinski on the five features they made together. Though Herzog has plenty to say about Kinski’s tantrums on the Peru locations of Aguirre: The Wrath of God and Fitzcarraldo and even interviews other witnesses on the same subject, he says next to nothing about his own involvement — such as why he hired Kinski in the first place or how the overreaching heroes Kinski played for Herzog were clearly modeled after the director, metaphorically speaking. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 14, 1988). — J.R.

TRACK 29

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Nicolas Roeg

Written by Dennis Potter

With Theresa Russell, Gary Oldman, Christopher Lloyd, Colleen Camp, Sandra Bernhard, and Seymour Cassel.

As a rule, I tend to be favorably disposed toward non-American movie depictions of American life, at least as a source of fresh perspectives. If we accept the premise that the U.S. continues to function as a stimulus for fantasy projections all over the world, here as well as everywhere else, it stands to reason that European projections about America would at least have the virtues of relative distance and detachment. Consequently, movies as diverse as Bunuel’s The Young One, Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point, Passer’s Born to Win, Demy’s The Model Shop, Wenders’s Hammett and Paris, Texas, and even — to cite two recent and contentious examples — Konchalovsky’s Shy People and Adlon’s Bagdad Cafe have things to tell us about this country that we would never learn from the likes of John Ford or Frank Capra. The truths of these movies may be more oblique and specialized (and harder to encapsulate) than those of our semiofficial laureates, but at least they give us some notion of how we look to outsiders. Read more

From the August 1, 1989 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

The greatness of Carl Dreyer’s first sound film (1932, 83 min.) derives partly from its handling of the vampire theme in terms of sexuality and eroticism and partly from its highly distinctive, dreamy look, but it also has something to do with Dreyer’s radical recasting of narrative form. Synopsizing the film not only betrays but misrepresents it: while never less than mesmerizing, it confounds conventions for establishing point of view and continuity, inventing a narrative language all its own. Some of the moods and images conveyed by this language are truly uncanny: the long voyage of a coffin, from the apparent viewpoint of the corpse inside; a dance of ghostly shadows inside a barn; a female vampire’s expression of carnal desire for her fragile sister; an evil doctor’s mysterious death by suffocation in a flour mill; a protracted dream sequence that manages to dovetail eerily into the narrative proper. The remarkable sound track, created entirely in a studio (in contrast to the images, which were all filmed on location), is an essential part of the film’s voluptuous and haunting otherworldliness. (Vampyr was originally released by Dreyer in four separate versions — French, English, German, and Danish; most circulating prints now contain portions of two or three of these versions, although the dialogue is pretty sparse.) Read more

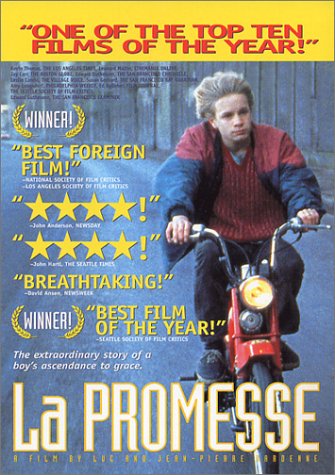

From the Chicago Reader (August 22, 1997). — J.R.

La promesse

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by Luc and Jean-Pierre Dardenne

With Jérémie Renier, Olivier Gourmet, Assita Ouedraogo, Frederic Bodson, Rasmane Ouedraogo, and Hachemi Haddad.

I’d never heard of Luc and Jean-Pierre Dardenne before I saw La promesse (1996), an important and highly involving movie playing at the Music Box this week. But given that they’re regional filmmakers working in an unfashionable country, this isn’t surprising. Based in Liege — a city in French-speaking western Belgium — the two brothers, both in their mid-40s, started out in the 70s as assistants to Belgian director and playwright Armand Gatti. They then made leftist videos about local urban and labor issues, followed by documentary films for TV about local anti-Nazi resistance, local workers’ struggles in the 60s, and a history of Polish immigration between the 30s and early 80s. In 1986 they turned to fiction, filming a play called Falsch, and their film made the rounds of a few international festivals. In 1991 they did a more experimental feature, Je pense à vous (“I’m Thinking of You”), cowritten by the distinguished New Wave screenwriter Jean Gruault, that apparently sank without a trace after playing at a few French festivals and being slaughtered by the Belgian press. Read more

Posted in (or on) Moving Image Source on August 18, 2010. — J.R.

“Having provided over 30 audio commentaries for DVD releases,” Australian film critic Adrian Martin wrote recently in his column for the Dutch film magazine Filmkrant, “I feel I have earned the right to criticize the format. These voice-over commentaries provided by filmmakers, critics and historians are decidedly a mixed blessing. I sometimes wonder whether anybody, except the most dedicated and/or masochistic researcher, ever listens to them all the way through. No one can doubt that these voice-tracks sometimes give us splendid insight or information that we cannot obtain elsewhere in print. But are they really the best we can do in the quest to marry film criticism with the film-object itself?”

Martin is hardly alone in articulating this position. Many of my friends who collect DVDs, maybe even most of them, avow that they tend to skip audio commentaries entirely, and it’s difficult not to share their bias In most of these run-on spiels, the remarks rarely coincide with what one is seeing (or hearing), and one often feels that the commentator, whether it’s a critic or a participant in the filmmaking, is simply taking the easy way out — doing a free-form improv rather than bothering to write a carefully considered text. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 7, 1994). — J.R.

One of the funnier remarks in Variety late last year came from a Universal Pictures executive who noted that because of the special nature of Schindler’s List his company wasn’t really promoting the picture, but simply informing people it was out. I’d wager that if the other movies on my ten-best list had been given the same amount of “nonpromotion” — one of those modest multimillion-dollar campaigns — you would have heard nearly as much about them. As it happens, only about half the items on my list have had — or are having — a normal commercial run in Chicago. Still, Bitter Moon, which has so far had only one fleeting engagement here (in the fall, at the Polish film festival), is expected to have a belated U.S. release early this year, and Silverlake Life: The View From Here was aired nationally on PBS.

The limited number of Hollywood films on my list and the prominence of Chinese language ones demands some comment. It used to be a truism that American cinema excelled in unpretentious entertainment but faltered when it came to art movies, while the standard line about foreign films — meaning the foreign films Americans saw — tended toward the reverse. Read more

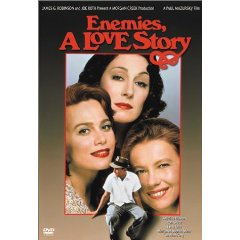

From the January 19, 1990 Chicago Reader. –J.R.

ENEMIES, A LOVE STORY

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Paul Mazursky

Written by Roger L. Simon and Mazursky

With Ron Silver, Anjelica Huston, Lena Olin, Margaret Sophie Stein, Alan King, Judith Malina, and Mazursky.

It’s a truism of film criticism that the best movie adaptations of novels usually aren’t taken from the best novels. A good novel, like a good movie, has its own raison d’être, and attempting to translate one person’s novel into another person’s movie usually entails removing the novel’s raison d’etre or at least transmogrifying it beyond recognition. A classic example of misplaced piety, in the sense of a movie trying to follow a novel too closely, is Joseph Strick’s Ulysses (1967): despite the fact that characters, settings, and entire textual passages from Joyce are all dutifully delivered and rendered, Joyce himself is absent from the movie. The personal, historical, and formal determinations of the book have nothing to do with those of the director of the film, working almost half a century later. The gap between Joyce’s reasons for writing Ulysses and Strick’s reasons for adapting it is so cosmically wide that the two sets of motivations aren’t even on speaking terms. Read more

This piece comes from the November 19, 1993 issue of the Chicago Reader. —J.R.

A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Elia Kazan

Written by Tennessee Williams and Oscar Saul

With Vivien Leigh, Marlon Brando, Kim Hunter, and Karl Malden.

FLESH AND BONE

** (Worth seeing)

Directed and written by Steve Kloves

With Dennis Quaid, Meg Ryan, James Caan, and Gwyneth Paltrow.

Depending on whose figures you believe, the recently released “director’s cut” of A Streetcar Named Desire is either 4 percent or 8 percent longer than the version released in 1951. All the originally censored elements — lines of “racy” dialogue and shots of lustful expressions — have been restored, and the fact that this once-scandalous 126-minute movie is now accorded a PG rating indicates the progress we’ve made in some areas.

But if you think people are getting more of the movie now than they could 42 years ago, you’re mistaken. The running time is longer, but thanks to current movie-projection habits, close to 25 percent of every frame is missing at most screenings. The aspect ratio of the original movie — the relationship between the height and width of the frame — is 1:1.38, the standard ratio of all Hollywood movies in 1951. Read more

From the September 3, 1999 Chicago Reader. It seems worth reposting because, I’m happy to report, both these films are now available on DVD. — J.R.

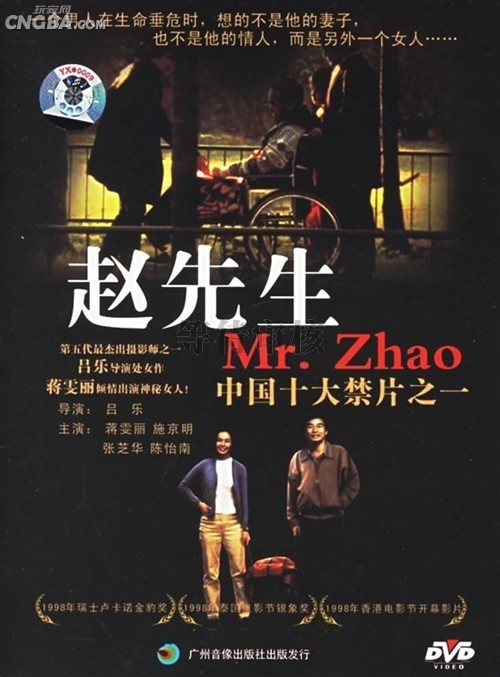

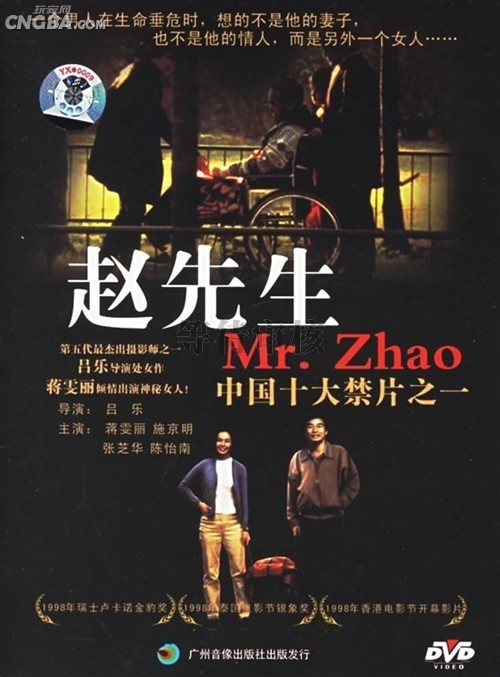

Mr. Zhao

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Lu Yue

Written by Shu Ping

With Shi Jingming, Zhang Zhihua, Chen Yinan, and Jiang Wenli.

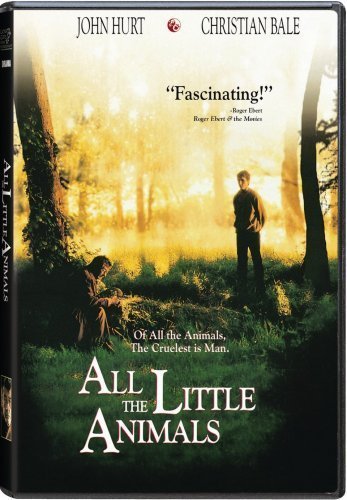

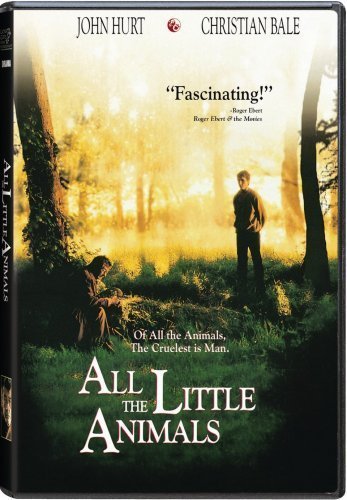

All The Little Animals

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Jeremy Thomas

Written by Eski Thomas

With John Hurt, Christian Bale, Daniel Benzali, James Faulkner, and John O’Toole.

Two of the best movies of 1998 are opening in Chicago this week — which makes them two of the best movies of 1999 — but the odds of either making much of a splash are just about nil. For one thing, they don’t appear to have opened previously anywhere else in the U.S., ruling out any advance buzz. For another, the budget for publicity in both cases appears to be about 15 cents; by contrast, the advertising budget for Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me was between $35 million and $40 million, not counting the Time Warner tie-ins (the entire production budget was $33 million). As a consequence, information about both films is hard to come by — I can’t even determine whether the screenwriter of Mr. Read more

From the April 17, 1998 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Eighteen Springs

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed by Ann Hui

Written by John Chan

With Leon Lai, Wu Chien-lien, Anita Mui, Ge You, Annie Wu, and Huang Lei.

I don’t know exactly what I think about Ann Hui’s 12th feature, playing twice this weekend at the Film Center. At this point I don’t think it’s a masterpiece — though that doesn’t necessarily mean you shouldn’t see it. Arriving at these two conclusions is something of a professional necessity for me, because whenever I write a long review for this paper I have to assign the film a certain number of stars; if you look at the box headed “film ratings” the meaning of those ratings is spelled out, from “masterpiece” (four stars) to “worthless” (none). But sometimes this necessity presents me with a dilemma, because my better instincts tell me that it’s often impossible to know immediately after seeing a film whether it’s a masterpiece or not. And while I’m at it, let me confess to another doubt, one that relates to the general inflation of rankings that infects my profession, whether critics are reviewing a Hollywood blockbuster or a Hong Kong art movie: I fear that if I tell people that Ann Hui’s Eighteen Springs (or the Coen brothers’ The Big Lebowski) is only “worth seeing,” a lot of them won’t bother to go — even if maybe some of them should, for their benefit, not mine. Read more