Written for The Unquiet American: Transgressive Comedies from the U.S., a catalogue/collection put together to accompany a film series at the Austrian Filmmuseum and the Viennale in Autumn 2009. — J.R.

Jerry Lewis’s opulent second feature as a director

(1961), in some ways his most ambitious (and his first

in color), is also the one that has the most to say

about his character’s sexual hysteria, intensified once

the hero discovers that he’s been hired to work as

houseboy in a boarding house full of sexy young aspiring

actresses -– all of whom are initially seen simultaneously

in their separate rooms as part of a single gigantic

dollhouse set occupying two soundstages at

Paramount. (To keep track of both this set and his

own performance, Lewis invented the video assist, a

filmmaking technique used in Hollywood filmmaking

ever since.) Furthermore, Lewis’s talent for freeform

psychic fantasy, which clearly distinguishes his

work from the social satire and narrative motivations

of Frank Tashlin, reaches a kind of apogee here when

he encounters a Bat Lady (shades of Artists and

Models) lurking inside a “forbidden” room, along

with the Harry James Orchestra. And his character is

no less free to dance with George Raft (playing himself)

in another sequence. Read more

This originally appeared in the May 23, 1997 issue of the Chicago Reader. –J.R.

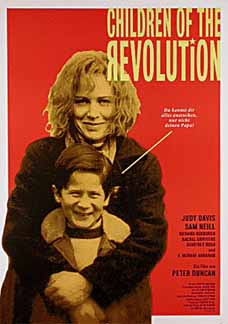

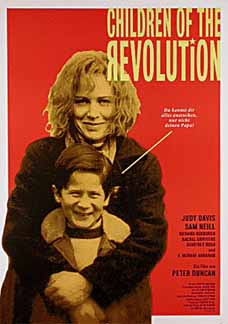

Children of the Revolution

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by Peter Duncan

With Judy Davis, Sam Neill, F. Murray Abraham, Richard Roxburgh, Rachel Griffiths, Geoffrey Rush, Russell Kiefel, John Gaden, Ben McIvor, Marshall Napier, Ken Radley, Fiona Press, and Alex Menglet.

This cockeyed story is recounted by several narrators in pseudodocumentary style (a style distantly patterned on Warren Beatty’s in Reds): various old codgers in present-day Australia speak to the camera about the past, their accounts leading into several extended flashbacks. Judy Davis plays Joan Fraser, a red-diaper baby who learned about Karl Marx from her father when he took her fishing. In 1949 — during the darkest days of the cold war — she’s a young woman who still dreams of a workers’ revolution and still idolizes Joseph Stalin. When Prime Minister Robert Gordon Menzies decides that Australia should follow the U.S. into Korea and outlaw communism and sign various anticommunist treaties, Fraser goes ballistic: she gets herself and her boyfriend, Welch (Shine’s Geoffrey Rush), ejected from a movie theater by causing a commotion during a newsreel, decides it would be OK to go to prison (“What do you people want — a discreet revolution?”), Read more

From the November 20, 1992 Chicago Reader. –J.R.

ROCK HUDSON’S HOME MOVIES

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed and written by Mark Rappaport

With Rock Hudson and Eric Farr.

In the creation of art, the verb is there to authenticate the subject with the same name.

To paint is the act of painting. . . . To write becomes the act of writing and of the writer. To film, that is, to record a sight and project it, is the act of cinema and of the makers of films . . .

Only television has no creative act or verb to authenticate it. That’s because the act of television both falls short of communication and goes beyond it. It doesn’t create any goods, in fact, what is worse, it distributes them without their ever having been created. To program is the only verb of television. That implies suffering rather than release. — Jean-Luc Godard

You were a great star, Mr. Hudson — one of the biggest. Sorry it all had to end like this. — director Mark Rappaport’s voice in Rock Hudson’s Home Movies

The precipitous decline in the quality of American movies since the 1970s can be attributed to several factors, but three interconnected changes in U.S. Read more