From Monthly Film Bulletin , vol. 44, no. 516, January 1977.

I’ve always been somewhat skeptical about Herzog’s reputation and constructed myth as a mad genius. Here are my capsule reviews for the Chicago Reader of Lessons of Darkness (1992) and My Best Fiend (1999), respectively (on other occasions, I’ve sometimes been more supportive of his work):

In his characteristically dreamy Young Werther fashion, Werner Herzog generates a lot of bombastic and beautiful documentary footage out of the post-Gulf war oil fires and other forms of devastation in Kuwait, gilds his own high-flown rhetoric by falsely ascribing it to Pascal, and in general treats war as abstractly as CNN, but with classical music on the soundtrack to make sure we know it’s art. This 1992 documentary may be the closest contemporary equivalent to Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will, both aesthetically and morally; I found it disgusting, but if you’re able to forget about humanity as readily as Herzog there are loads of pretty pictures to contemplate. 54 min.

Werner Herzog’s surprisingly slim and relatively impersonal 1999 feature charts his relationship with the mad actor Klaus Kinski on the five features they made together. Though Herzog has plenty to say about Kinski’s tantrums on the Peru locations of Aguirre: The Wrath of God and Fitzcarraldo and even interviews other witnesses on the same subject, he says next to nothing about his own involvement — such as why he hired Kinski in the first place or how the overreaching heroes Kinski played for Herzog were clearly modeled after the director, metaphorically speaking. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 14, 1988). — J.R.

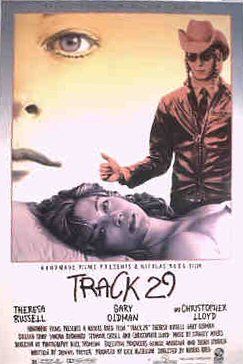

TRACK 29

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Nicolas Roeg

Written by Dennis Potter

With Theresa Russell, Gary Oldman, Christopher Lloyd, Colleen Camp, Sandra Bernhard, and Seymour Cassel.

As a rule, I tend to be favorably disposed toward non-American movie depictions of American life, at least as a source of fresh perspectives. If we accept the premise that the U.S. continues to function as a stimulus for fantasy projections all over the world, here as well as everywhere else, it stands to reason that European projections about America would at least have the virtues of relative distance and detachment. Consequently, movies as diverse as Bunuel’s The Young One, Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point, Passer’s Born to Win, Demy’s The Model Shop, Wenders’s Hammett and Paris, Texas, and even — to cite two recent and contentious examples — Konchalovsky’s Shy People and Adlon’s Bagdad Cafe have things to tell us about this country that we would never learn from the likes of John Ford or Frank Capra. The truths of these movies may be more oblique and specialized (and harder to encapsulate) than those of our semiofficial laureates, but at least they give us some notion of how we look to outsiders. Read more

From the August 1, 1989 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

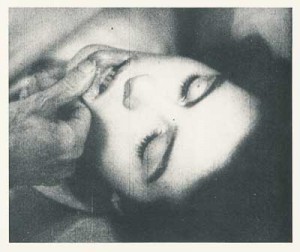

The greatness of Carl Dreyer’s first sound film (1932, 83 min.) derives partly from its handling of the vampire theme in terms of sexuality and eroticism and partly from its highly distinctive, dreamy look, but it also has something to do with Dreyer’s radical recasting of narrative form. Synopsizing the film not only betrays but misrepresents it: while never less than mesmerizing, it confounds conventions for establishing point of view and continuity, inventing a narrative language all its own. Some of the moods and images conveyed by this language are truly uncanny: the long voyage of a coffin, from the apparent viewpoint of the corpse inside; a dance of ghostly shadows inside a barn; a female vampire’s expression of carnal desire for her fragile sister; an evil doctor’s mysterious death by suffocation in a flour mill; a protracted dream sequence that manages to dovetail eerily into the narrative proper. The remarkable sound track, created entirely in a studio (in contrast to the images, which were all filmed on location), is an essential part of the film’s voluptuous and haunting otherworldliness. (Vampyr was originally released by Dreyer in four separate versions — French, English, German, and Danish; most circulating prints now contain portions of two or three of these versions, although the dialogue is pretty sparse.) Read more