Daily Archives: July 30, 2024

Entries in 1001 MOVIES YOU MUST SEE BEFORE YOU DIE (the fourth dozen)

These are expanded Chicago Reader capsules written for a 2003 collection edited by Steven Jay Schneider. I contributed 72 of these in all; here are the fourth dozen, in alphabetical order. — J.R.

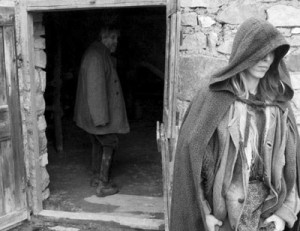

Taste of Cherry

A middle-aged man who’s contemplating suicide drives around the hilly, dusty outskirts of Tehran trying to find someone who will bury him if he succeeds and retrieve him if he fails. This minimalist yet powerful and life-enhancing feature by Abbas Kiarostami (Where Is the Friend’s House?, Life and Nothing More, Through the Olive Trees) never explains why the man wants to end his life, and is even inconclusive about whether or not he succeeds, yet every moment in his daylong odyssey carries a great deal of poignancy and philosophical weight. The film has remained in many ways Kiarostami’s most controversial film ever since it shared the 1997 paume d’or at Cannes with Shohei Imamura’s The Eel, in part because it entrusts so much of its meaning and power to the audience and the nature of its own investment in what it’s watching. Like many of Kiarostami’s other films, it’s centered around the simultaneously private and public experience of a character in a car giving rides to others, and just as the experience of watching a film in a theater combines private responses with public reactions, this is a film that speaks to both of these situations. Read more

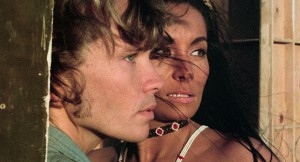

Watch with Mother [on Carl Dreyer]

From The Guardian (May 30, 2003). –J.R.

For roughly two decades, my three favourite dramatic features have all been the work of the same man — and my favourite among these depends almost entirely on which one I’ve seen most recently. I came to know and love them in reverse order: first the incandescent and subtly erotic Gertrud (1964), discovered in my early 20s shortly after it premiered; then the gut-wrenching Ordet (1955), which I initially hated when I first saw it in my teens, misconstruing its climactic miracle as a tool of religious propaganda; and finally the voluptuous and mysterious Day of Wrath (1943), which I didn’t appreciate or understand until my 40s, when I finally saw it in a decent 35mm print.

Like all the greatest artists, Carl Theodor Dreyer demands to be taken as a figure whose work continues to grow and change, quite irrespective of the fact that he died in 1968 at the age of 79, with many of his most cherished projects (most notably, a film about Jesus) unrealised. Fresh insights about his life and career keep coming to light: not only through biographical research; the emergence of new prints (such as the remarkable 1981 rediscovery of the original 1927 version of The Passion of Joan of Arc in an Oslo mental hospital); but also through the uncanny fact that his films seem to grow more multilayered, ambiguous, and complex over time. Read more