Written for the Chicago Film Festival and the Gene Siskel Film Center’s week-long streaming of this masterpiece (April 24-30). — J.R.

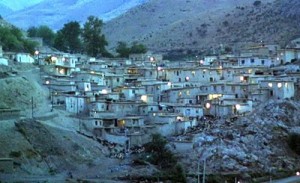

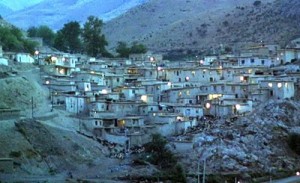

Vitalina Varela

It isn’t necessary to have seen anything by Portuguese master Pedro Costa before encountering the title heroine here, but if you saw his previous feature, Horse Money, you’ve already met her—a striking, angry middle-aged woman from Cape Verde who finally found the money to fly to Lisbon to join her long-absent husband, only to discover that she just missed his funeral. Settling into his rickety, crumbling house and trying to come to terms with her grief, keeping company mainly with a semi-mad priest (Costa regular Ventura), she’s precisely the kind of person that the world and movies tend to ignore but Costa’s epic portraiture, so beautifully lit and framed that it becomes jaw-dropping, builds an exalted altar to her, inviting us to luxuriate in her hushed presence. Audiences tend to have an easier time with this dark reverie than critics because it takes us somewhere very special and respects us far too much to tell us why. (Jonathan Rosenbaum)

Read more

Read more

The following was commissioned by and written for Asia’s 100 Films, a volume edited for the 20th Busan International Film Festival (1-10 October 2015). — J.R.

This ambiguous comic masterpiece of 1999 might be Abbas Kiarostami’s greatest film to date; it’s undoubtedly his richest and most challenging. A media engineer from Tehran (Behzad Dourani) arrives in a remote mountain village in Iranian Kurdistan, where he and his three-person camera crew secretly wait for a century-old woman to die so they can film or tape an exotic mourning ritual at her funeral. To do this he has to miss a family funeral of his own, and every time his mobile phone rings the poor reception forces him to drive to a cemetery atop a mountain, where he sometimes converses with Youssef, a man digging a deep hole for an unspecified telecommunications project. Back in the village the digger’s fiancée milks a cow for the engineer while he flirts with her by quoting an erotic poem by Forough Farrokhzad that gives the movie its title, in a seven-minute sequence that figures as the film’s centerpiece, summarizing all its themes, conflicts, and power relations. (“I’m one of Youssef’s friends — in fact, I’m his boss,” the media engineer remarks smugly at one point.) Read more

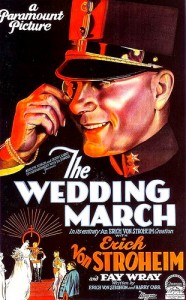

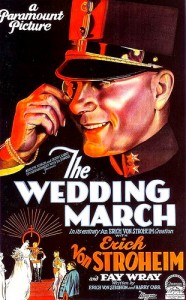

My thanks to Joseph McBride, who originally posted this text on December 8, 1999, at the tail end of an interview with Rick Schmidlin about his expanded version of Greed on a now-defunct website, CreativePlanet.com. I’ve omitted the Schmidlin interview here, but hope that Rick’s version (as well as the original MGM release version) will become available in this country on DVD and/or Blu-Ray — releases that are scandalously overdue. — J.R.

In the June 12, 1927, Directors’ Number of the Hollywood trade publication The Film Daily, each of the 10 directors chosen as the leading directors of the day selected his favorite film. The following is Erich von Stroheim’s contribution:

Erich von Stroheim selects Greed.

Of course, the picture on which I have my heart set the most at present is The Wedding March on which I have been working the past year and a half, but inasmuch as this picture has not been released, I will only dwell on past performances.

Looking back over the few productions I have done and endeavoring to calmly and dispassionately analyze each, there is just one that presents itself to my mind as being worthy of classification in your “What I Consider My Best Picture — And Why.” Read more