I will be reprinting the entirety of my first and most ambitious book (Moving Places: A Life at the Movies, New York: Harper & Row, 1980) in its second edition (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995) on this site in eleven installments. This is the first.

Note: The book can be purchased on Amazon here, and accessed online in its entirety here. — J.R.

Acknowledgments

For specific, invaluable, and diverse forms of assistance to me in preparing this book, I owe particular thanks to Lizzie Borden, Meredith Brody, W. L. and Diane Butler, Ian Christie, David Ehrenstein, Aston and Mae Murray Elkins, Manny Farber, Carolyn Fireside, Sandy Flitterman, Vicki Hiatt, Penelope Houston, Allan Kronzek, Lorenzo Mans, David Meeker, Cynthia Merman, Patricia Patterson, Carrie Rickey, Paul Schmidt, Allan Sekula, Wally Shawn, Charles Silver, David Sobelman, Bobby Stewart, Beulah Sutton, Amos Vogel, and Bibi Wein;

the staffs of the Florence Public Library, Florence, Alabama; the Information Department at the British Film Institute in London; the Film Study Center at the Museum of Modern Art in New York; the Motion Picture Division of the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.;

and National Endowment for the Arts, for an Art Critics Fellowship Grant which permitted me to launch this project in 1977. Read more

From Film Comment (March-April 1974). — J.R.

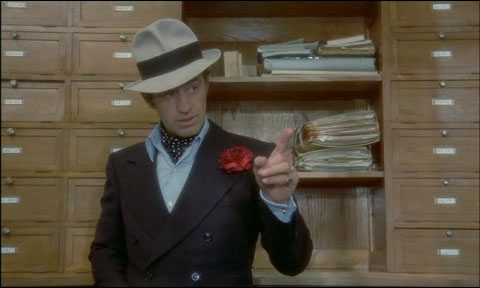

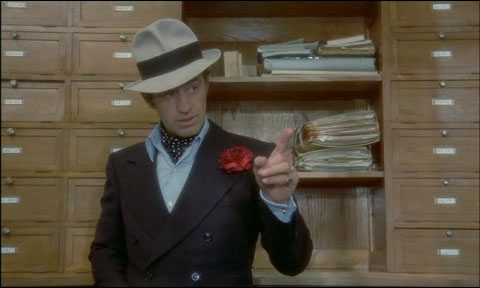

December 7: To enter the sound stage at Epinay-sur-Seine, a Parisian suburb where Alain Resnais is working on his new film about Alexandre Stavisky, you have to go through a heavy door that resembles the entrance to a bank vault, where you’re promptly greeted by Alexandre, a friendly dog who seems to be serving as the crew’s mascot (a younger dog named Sacha figures in the cast). Continuing past Alexandre, you weave your way through a labyrinth of construction that eventually resolves itself into a gargantuan neo-Lubitsch set comprising Stavisky’s office complex — a rather awesome 1933 décor the size of a country house that took forty people a month to build, even though it’ll only be used for a relatively short part of the film.

It’s the kind of set you can get lost in, with multiple exits and three separate stairways leading off of a giant central conference room with golden chandeliers, a large semi-circular table, light-green walls, tall windows with pink drapes, and no ceiling; a set where long hallways on the second landing go past doors that open on nothing, and members of the lighting crew move about in obscure corners carrying equipment and muttering to themselves. Read more

From Sight and Sound (Winter 1974-75). — J.R.

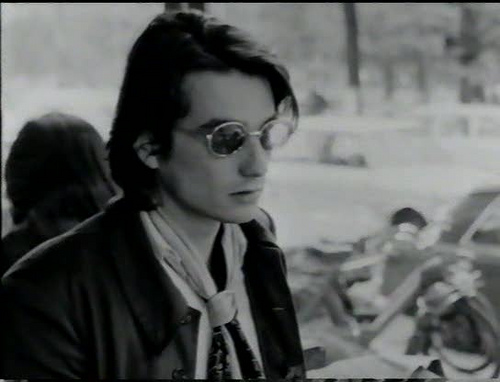

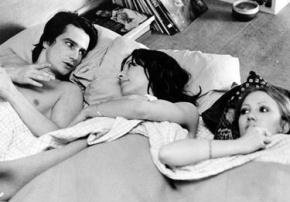

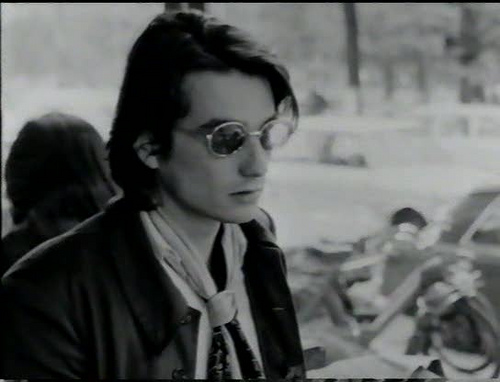

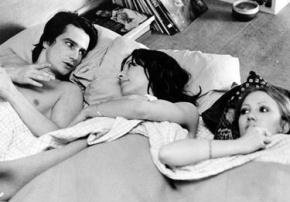

“The day I stop suffering, I’ll have become someone else.” “There’s no such thing as chance.” “To speak with the words of others — that’s what I’d like. That’s what freedom must be.” From the Café aux Deux Magots to the adjacent Flore, from the streets and sidewalks of a grayish Paris to other people’s flats, for the better part of 219 minutes, Alexandre (Jean-Pierre Léaud) continues to hold forth. “In May ’68 a whole café was crying. It was beautiful. A tear-gas bomb had exploded . . . a crack in reality opened up.” Charmingly, narcissistically, elaborately, endlessly: “I don’t do anything; I let time do it.” “Abortionists are the new Robin Hoods . . .the scalpel replaces the sword.” “The world will be saved by children, soldiers” (pregnant pause) “and fools.”

Much less talkative is his beloved Gilberte (Isabelle Weingarten—a Bresson discovery back for another nonperformance), who forsakes him to get married, and Marie (Bernadette Lafont), the older woman he lives with, casually exploits, and is clothed and fed by. But a verbal match of sorts is offered by the doleful and doelike Veronika (Françoise Lebrun, in an extraordinary, glowing debut), a promiscuous nurse he picks up one afternoon. Read more