A post on the Chicago Reader‘s blog, Bleader. — J.R.

Film Rotterdam #2: Another venue, another timetable

It’s hard at many festivals apart from the biggest ones to determine whether a film is really “new” or not: “new” in relation to where? I was fortunate enough to attend the world premiere of Jia Zhangke’s Still Life in Venice last year and then resee it in Toronto a week or so later. It’s playing in Rotterdam now, and perhaps it will reach Chicago a year from now, or maybe a little sooner. In the busy cafe-bar of the Lantaren/Venster, the oldest of the festival’s three multiscreen multiplexes (where virtually the entire festival was taking place the first year I attended, 1984), between two programs, I buy a Chinese DVD of this film, priced around $10 in Euros from a clerk who assures me that this version has English subtitles, even though they aren’t mentioned on the box — something I may not be able to confirm until I’m back in Chicago next month. But then, just before a Chinese indy film called Weed starts a few minutes later, I find I’m sitting a row away from Chinese film expert and sometime Reader reviewer Shelly Kraicer, who assures me that (1) this version is subtitled, and (2) it can be bought on the streets of Beijing for about $1.10 — or 80 cents if it’s from a pirated source. Read more

From Film Comment (September-October 1998). This is a restructured and substantially revised, updated, and otherwise altered version of my “Trailer for Histoire(s) du cinéma,” which appeared originally in French in the Spring 1997 issue of Trafic. Among the more important changes are a suppression of virtually all of my multiple comparisons of Histoire(s) du cinéma with Finnegans Wake in the original (which, paradoxically, seemed more appropriate in a French publication than in an American one), an expansion of much of the interview material, and an extended quotation from Godard’s review of Rob Tregenza’s Talking to Strangers.

My apologies for some format irregularities that I wasn’t able to fix. -– J.R.

GODARD AS CRITIC

JLG (at press conference): I still look at movies the same way today than I did [at the time of the New Wave], but I know it’s not the same world, exactly. Even if we enter the theater the same way, we don’t go out the same way.

Q: How is it different? Read more

From Film Comment (September-October 1998). This is a restructured and substantially revised, updated, and otherwise altered version of my “Trailer for Histoire(s) du cinéma,” which appeared originally in French in the Spring 1997 issue of Trafic. Among the more important changes are a suppression of virtually all of my multiple comparisons of Histoire(s) du cinéma with Finnegans Wake in the original (which, paradoxically, seemed more appropriate in a French publication than in an American one), an expansion of much of the interview material, and an extended quotation from Godard’s review of Rob Tregenza’s Talking to Strangers.

My apologies for some format irregularities that I wasn’t able to fix. -– J.R.

Part of the following derives from two film festival encounters — a panel discussion on Godard’s Histoire(s) du cinéma held in Locarno in August 1995, and some time spent with Godard in Toronto in September 1996. I participated in the first event after having seen the first four chapters of Godard’s eight-part video series; unlike my co-panelists, I’d been unable to accept Godard’s invitation to view chapters 3a and 3b, devoted to Italian neorealism and the New Wave, in Rolle a few days earlier. Read more

From “Film Criticism in America Today: A Critical Symposium,” Cineaste 26, no. 1, 2000. This is the first of several symposia gathered in a new collection edited by Cynthia Lucia and Rahul Hamid, Cineaste on Film Criticism, Programming, and Preservation in the New Millennium, Austin: University of Texas Press, 2017. –- J.R.

Here are my replies to the following questions from Cineaste:

1. What does being a film critic mean to you? (More specifically, why do you write film criticism? Whom do you hope to reach, and what do you hope to communicate to them?)

2. What qualities make for a memorable film critique? (Do you think such critiques tend to be positive or negative in tone? Is discussing a film’s social or political aspects as important to you as its cinematic qualities and value as art or entertainment?)

3. How would you characterize the relationship between film critics and the film industry? Do you think film critics could be more influential in this relationship? How?

4. What are the greatest obstacles you face in writing the kind of film criticism you wish to write? (For example, does your publication require delivery of your copy on a short deadline after only one screening, limit the space available for your reviews, or dictate which films you should review? Read more

Written for Whose Cinema?, a Critics’ Choice Slow Criticism Project booklet published at the Rotterdam International Film Festival, January 27 — February 7, 2016, and in the February 2016 issue of the online Filmkrant. — J.R.

“Back then [in Hungary in the late 1970s], it was the censorship of the politics, and now we have the censorship of the market. What has changed? The climate is the same. If you are a filmmaker, it is always fucked up.”

–Béla Tarr at the Walker Art Center (Minneapolis), 2012

“Piracy isn’t a victimless crime,” is what we read at the beginnings of an inordinate number of DVDs and Blu-Rays — to which I’m often tempted to reply that capitalism isn’t always or invariably a victimless crime either, especially when the victim turns out to be the consumer. And the fact that piracy is usually regarded as a crime and capitalism usually isn’t should mark the beginning of any clear-headed discussion of who (or what) cinema should belong to.

If “Whose cinema?” is a question that needs to be answered, we first have to add another question, and an even thornier one — “What cinema (or whose cinema) are we talking about?” Read more

The following was commissioned by and written for Asia’s 100 Films, a volume edited for the 20th Busan International Film Festival (1-10 October 2015). — J.R.

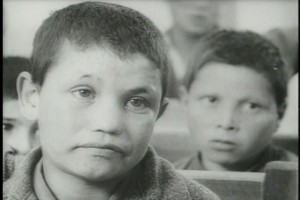

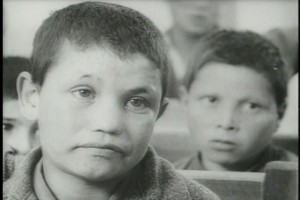

The House is Black is the most acclaimed of all Iranian documentaries. It was directed by Forough Farrokhzad (1935-1967), widely regarded as the greatest of all Iranian women poets and the greatest Iranian poet of the 20th century, who died in a car accident when she was only 32. It was Farokhzad’s only film, produced in 1962 by her lover Ebrahim Golestan (an important filmmaker in his own right, for whom she also worked as an editor, and who serves as one of the film’s narrators). The film observes the tragic life of lepers in an isolated leprosy hospital (a hell on earth and a nest of suffering and death) near Tabriz in northwestern Iran. The Society for Assisting Lepers commissioned the film, and the director’s intention was “to wipe out this ugliness and to relieve the victims.”

Farrokhzad avoids infringement by creating a close relationship with the lepers, and by searching for the seeds of joy and vitality within the hopelessness. She depicts the inhabitants in their daily occupations, having meals, praying, the children playing ball and attending school. Read more

Whoever said that cinema and film criticism aren’t international languages?

http://apaladewalsh.com/2014/06/15/joao-benard-da-costas-johnny-guitar-play-it-again-in-nine-tongues/

[6/16/14] Read more

In most respects, I’m delighted and honored that a version of the following essay was published in Issue Two of the journal Music & Literature, which is devoted to László Krasznahorkai, Béla Tarr, and Max Neumann, In fact, this essay was commissioned by the editors of this handsome special issue, and my only reason for posting my original version is that a few stylistic edits were made, in what I’m sure were sincere efforts to clarify some of the entanglements in my lengthy sentences, that unfortunately yielded some embarrassing factual errors in the piece, as well as a few significant cuts. (It now appears that I read portions of the French translation of Krasznahorkai’s novel before I ever saw Tarr’s film and that Erich Auerbach’s great book Mimesis now includes an analysis of Light in August that no one has previously read; and the remarkable observation from Dan Gunn that I quoted has been deleted.) So, just to keep the record straight, here, for better and for worse, is exactly what I wrote. More recently, in mid-January 2015, I belatedly received a copy of this article with the above Introduction reprinted in Scalarama, a publication put together by Stanley Schtinter to accompany a tour of Sátántangó in the U.K. Read more

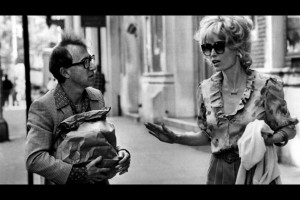

Preparing a book about Woody Allen, biographer Patrick McGilligan sent out a poll to me and many others, and here are my responses to his questions:

THE WOODY ALLEN POLL

1. What five Woody Allen films do you hold in the highest regard?

(List the five in any order. One equal point will be assigned to each of your choices for the cumulative total to be listed from 100 participating critics and scholars.)

What’s Up, Tiger Lily?

Annie Hall

Broadway Danny Rose

Oedipus Wrecks

Manhattan Murder Mystery

2. What do you believe about the allegation by Dylan Farrow, Allen’s adopted daughter, that he sexually molested her?

c. Undecided.

3. Have the Dylan Farrow allegations, or his marriage to Mia Farrow’s adopted daughter Soon-Yi Previn – either or both – affected your view of his film?

No.

4. How has his over-all legacy been affected? Comments are welcome.

I’ve always thought he was overrated (cf. my “Notes Toward the Devaluation of Woody Allen”). If his reputation and legacy as an artist have been tarnished by these unconfirmed charges or his marriage, this only illustrates the public’s lack of seriousness about art. I find Allen’s far more confirmable shame and embarrassment about his working-class origins and his middle-class values far more relevant to the importance and (lack of) depth of his work. Read more

Published as “Classic Touch” in the January 2002 issue of AMC: American Movie Classics Magazine….The last photo reproduced here is of the whole crew of the re-edit team at the Cannes Film Festival in May 1998. — J.R.

Considering all the rereleases in recent years of studio classics that are

labeled “director’s cut,” it must seem like every studio picture has one.

But the phrase is often a marketing term, and therefore potentially

misleading. There are some movies, including a few great ones, that can’t

be released in “director’s cuts” because the director was never accorded

final cut in the first place. At least five of Orson Welles’s European films

and three of his Hollywood features have director’s cuts, but Touch of

Evil (1958), his last Hollywood movie, isn’t one of them. (For the record,

his three director’s cuts are all in the 1940s: Citizen Kane and two

separate edits of his Macbeth.)

Admittedly, there was less studio interference on this noir thriller than

there had been on Welles’s The Magnificent Ambersons, The Stranger,

and The Lady from Shanghai. Welles was allowed to direct and rewrite

the script only after he’d been cast as the heavy, a crooked cop — mainly

through the intervention of lead actor Charlton Heston, who played an

honest Mexican cop. Read more

It’s sad to hear about the death of my friend Edgardo Cozarinsky, a writer and director, in Buenos Aires, at age 85, but the sadness belongs to his friends rather than to Edgardo himself, because I believe he had a rich and full life.

The following text, commissioned by Edgardo himself for a retrospective held in Paris, was reprinted in my original English in the September-October 1995 issue of Film Comment. I should stress that this essay is very much out of date once one starts to consider Cozarinsky’s prolific subsequent career as both a writer and a filmmaker — although I’ve anachronistically included some more recent book covers and film posters as illustrations, as well as a poster and two stills from the 2005 Ronda Nocturna, known in English as Night Watch, in part to help make up for the impossibility of finding stills for some of the rarer films of his discussed here.

Let me also quote my Reader capsule review of Night Watch: “With a few exceptions, I prefer the literature of Edgardo Cozarinsky, an Argentinean based mainly in Paris, to his films, and his nonfiction in both realms to his fiction. But this poetic, atmospheric drama, shot in Buenos Aires, challenged my bias, mixing the natural and the supernatural, the cinematic and the literary, with such assurance that Cozarinsky no longer seems like a divided artist. Read more

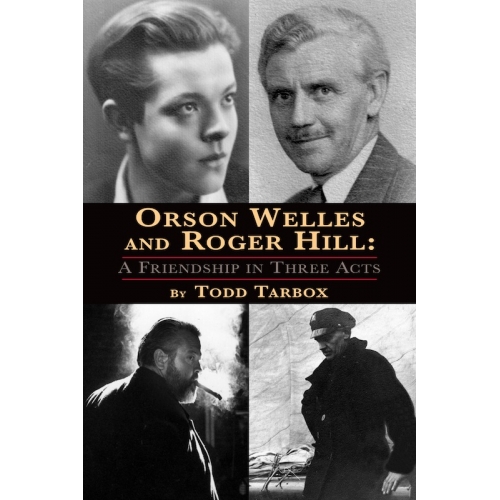

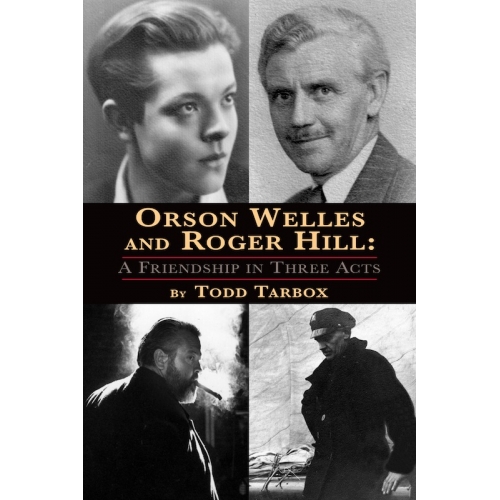

Almost seven years have passed since I quoted from the manuscript of this wonderful book in the Introduction to my own Discovering Orson Welles. At that point the subtitle of Todd Tarbox’s book was A Friendship in Four Acts, but if anything, the book has only grown since then, both physically and in terms of readability. In short, it’s been well worth the wait. (June 2014 footnote: For more details, including an excerpt from one of the Welles/Hill conversations, go to Todd Tarbox’s radio interview with Rick Kogan, here.) — J.R.

The major and longest-lasting close friendship of Orson Welles’s life was with one of his earliest role models — his teacher, advisor, and theatrical mentor at the Todd School who later became the school’s headmaster, Roger Hill. By editing and arranging many of their recorded conversations at the end of Welles’s life and career, Hill’s grandson, Todd Tarbox, has given us invaluable and candidly intimate glimpses into many of its stages, especially ones towards the beginning and end of that diverse and complicated saga. In the process, he also confounds and complicates the array of “weak” and flawed father figures that populate most of Welles’ films, all the way from Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersonsthrough The Trial, Chimes at Midnight, Don Quixote, and The Other Side of the Wind, with a bracing and ennobling alternative to that pattern, an unwavering relationship of mutual admiration and respect that was a clear source of strength to both of them. Read more

All three of the following short reviews appeared in the June 1975 issue of Monthly Film Bulletin (vol. 42, no. 497). The reason why I had to cover so many films of this kind for the magazine was that I was the assistant editor, and it was very hard to convince most of our freelance reviewers (apart from Tom Milne) to take them on. -– J.R.

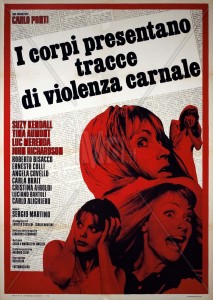

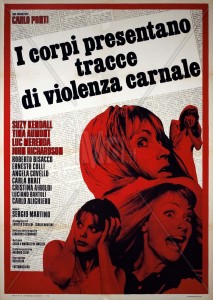

Corpi Presentano Tracce di Violenza Carnale. I (Torso)

Corpi Presentano Tracce di Violenza Carnale. I (Torso)

Italy, 1973

Director: Sergio Martino

After two college girls, Florence and Carol, are savagely murdered and butchered by a masked assailant, one of their classmates, Daniela, recalls having recently seen the scarf left behind by the murderer but can’t remember who was wearing it. Before long, she receives an anonymous threatening phone call, and her uncle Nino requests that she so for a rest to his country villa with her school friends Ursula, Katia and Jane. Jane stays behind briefly to look up Stefano — a student whom she suspects is the killer, but who proves not to be at home — and passes up an invitation to attend a concert with her art professor Franz. A scarf-dealer who meanwhile tries to blackmail the killer by phone manages to collect 3 million lire, but is then run down by a car; that evening, after a local shoe-peddler spies Ursula seducing Katia in the country house, he is pursued, killed and thrown into a well by the masked assailant. Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, February 1975 (vol. 42, no. 493). -– J.R.

Swedish Wildcats

U.S.A./Sweden, 1974

Director: Joseph W. Sarno

Copenhagen. Margareta, a brothel madam who displays her prostitutes in elaborate cabaret revues at private parties, summons her two orphan nieces Susanna and Karen — both part of her entourage — to participate in a ‘slave auction’ staged for some local clients. Gerhard Jensen, chief of a ground crew handling air cargo, bids for Karen and then offers to pay extra to share a room with Susanna and his friend; Margareta agrees and watches the results through a two-way mirror: Gerhard complains to Karen, “I could get more excitement from a piece of raw liver”, and tries to make love to Susanna, then beats her when she refuses to kiss him on the mouth. In a park, Susanna meets Peter Borg, another member of Gerhard’s crew; it is love at first sight, and she presents herself as Natasha, a ballet dancer, while he claims to be a test pilot working on a secret project. Meanwhile, her sister Karen has also fallen in love with someone who doesn’t know her profession — Gabriel, an architect from a very respectable family. Read more

This was written in the summer of 2000 for a coffee-table book edited by Geoff Andrew that was published the following year, Film: The Critics’ Choice (New York: Billboard Books). — J.R.

A recent documentary about communist musicals called East Side Story (Dana Ranga, 1997) assumes that communist-bloc directors were just itching to make Hollywood extravaganzas and invariably wound up looking strained, square, and ill-equipped. But Red Psalm (1971), Miklós Jancsó’s dazzling, open-air revolutionary pageant, is a highly sensual communist musical that employs occasional nudity as lyrically as the singing, dancing, and nature. That is to say, within its own specially and exuberantly defined idioms, it swings as well as wails.

Set near the end of the 19th century, when a group of peasants have demanded basic rights from a landowner and soldiers arrive on horseback to quell the uprising, Red Psalm is composed of only 26 shots. (With a running time of 84 minutes, this adds up to an average of three minutes per shot. Jancsó’s earlier feature from 1969, Winter Sirocco, is said to consist of only 13 shots.) Each long take is an intricate choreography of panning camera, landscape, and clustered bodies that constantly traverse, join, and/or divide the separate groups. Read more