From the March 6 1996 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

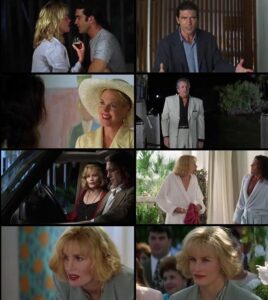

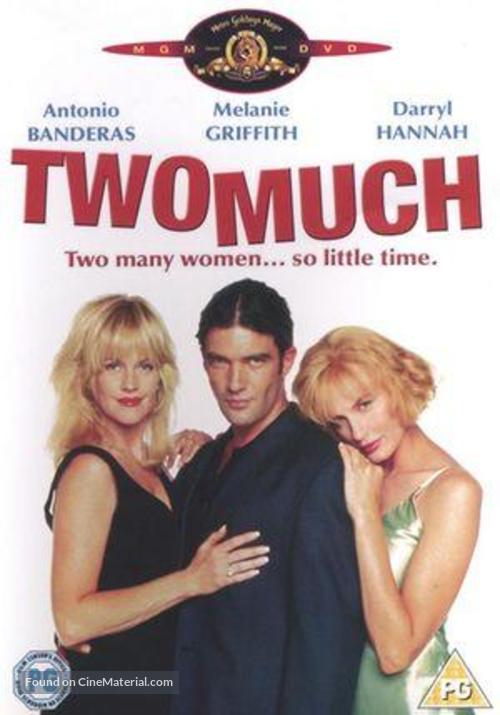

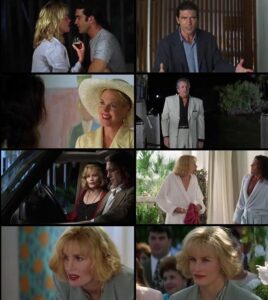

Or should we say knot enough? Antonio Banderas plays a frustrated painter and crooked art dealer who pretends to be twin brothers while romancing wealthy sisters played by Melanie Griffith and Daryl Hannah. Spanish director Fernando Trueba, who with his brother David Trueba has adapted a Donald E. Westlake novel, easily surpasses his comic work on the overrated and Oscar-winning Belle Epoque; but he fails to take the knots — which might also be called the flabby stretches — out of an overextended farce. I could live with this movie because the cast (which also includes Danny Aiello, Joan Cusack, and Eli Wallach) is so agreeable, but Banderas, for one, has to strain too hard and too long for his laughs, and the relatively lackadaisical pacing forces him to do so. (JR)

Read more

From the November-December 1981 issue of Film Comment. I was gratified to learn from David Bordwell, via his own web site (as well as an email to me), that he’s eventually come around to agreeing with my major complaint about his book. (For an update to his link to my subsequent essay about Gertrud, go here. However, his link to this essay no longer works, so here’s one that does.)

The photograph of Dreyer immediately below is by Jonas Mekas. — J.R.

The Films of Carl-Theodor Dreyer by David Bordwell. 251 pp., illustrations, index, University of California Press, $29.50

In relation to Roland Barthes’ distinction between readerly and writerly texts, David Bordwell — an academic marvel who organizes huge masses of material with an uncanny sense of what can or can’t be assimilated –- should be considered a master of the teacherly text. His ambitious textbook written with Kristin Thompson, Film Art: An Introduction (Addison-Wesley, 1979), has rightly been regarded as a landmark to many film teachers — a sort of Whole Systems Catalog of formal registers in film that, like Dudley Andrew’s The Major Film Theories, makes a good bit of relatively difficult material accessible to students. Read more

Symphonies in Black: Duke Ellington Shorts

A programme by Jonathan Rosenbaum and Ehsan Khoshbakht (Il Cinema Ritrovato, Bologna, June 2024)

Introductory note by Jonathan Rosenbaum

In 16 shorts made over a stretch of almost a quarter of a century (1929-1953), Duke Ellington and his Orchestra perform in a variety of settings, often with dancers and singers – including Billie Holiday in Symphony in Black: A Rhapsody of Negro Life. The latter cuts freely between Ellington alone in thoughtful composing mode, Ellington in a tux performing the same extended composition with his band at a concert, arty images of men engaged in heavy labour, a wordless church sermon, a nightclub floorshow, and even a short stretch of story showing Holiday being pushed to the ground by an ungrateful lover before singing there about her misery – a near replica of the musical setup accorded to Bessie Smith in her only film appearance six years earlier.

Indeed, although the pleasures to be found here are chiefly musical, the narrative pretexts for these performances offer a fascinating look at how both jazz and Black musicians were perceived and expected to behave during the first three decades of talkies. At least half of the films are Soundies made for sound-and-image jukeboxes in the 40s, but even these often trade on narrative details such as the adoring women digging the solos by Ray Nance, Rex Stewart, Ben Webster, and others at an “eatery” after hours in Jam Session (1942), or the spectacular dancing by athletic jitterbugging couples in Hot Chocolate (Cottontail) from the same year. Read more

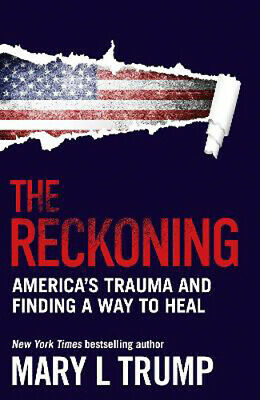

The merit of Mary L. Trump’s energizing and persuasive new book, The Reckoning: Our Nation’s Trauma and Finding a Way to Heal, which usefully combines psychology with our national history, is its demonstration of the diverse ways that denial shapes not only much of our politics but most of our media. It might also be argued that, as Mary Trump periodically implies, the principal agent of that denial is capitalism, which trumps democracy (pun intended) whenever it can.

The main form of denial Mary Trump’s book is concerned with is related to the trauma caused by American genocide and enslavement and the myth of white supremacy that has sought to justify and sustain these practices, but it applies equally well to the history of this country’s obscurely motivated and ill-defined wars, most recently the military occupation of Afghanistan. The media’s emphasis on the messinessn of our military withdrawal is predicated entirely on capitalist assumptions that (1) messiness is always what people want to watch the most, (2) ignoring and in effect denying the messiness of previous unnecessary wars to make the end of the present one seem unique and unprecedented. Our other military occupations, and our eventual messy withdrawals (e.g., Read more