A column for the Spanish magazine Caimán Cuadernos de Cine. I believe it was written circa May 2014-. J.R.

En movimiento: Welles in Woodstock

Jonathan Rosenbaum

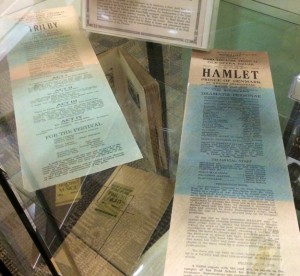

I’ve recently returned from Woodstock Celebrates Orson Welles, a delightful two-day event in Illinois (16-17 May) organized by Kathleen Spaltro and commemorating the 80th anniversary of the Todd Theatre Festival held at the Woodstock Opera House in 1934, orchestrated by Welles at the age of 19 and sponsored by his mentor and one of his lifelong best friends, Roger Hill — headmaster of the Todd School for Boys, which Welles attended from 1926 to 1930.

When Welles graduated from Todd, Hill wanted him to attend Harvard while Welles’ guardian, Dr. Maurice Bernstein (whom Everett Sloane’s character in Citizen Kane was named after), hoped he would go to Cornell. But Welles, still under the spell of an article published by one of Chicago’s leading drama critics, Ashton Stevens (who wrote for the Chicago Herald-American, a Hearst newspaper, and was the model for Jed Leland in Kane), predicting that the young genius was destined to become a major actor, didn’t want to go to college. So a compromise was struck: Welles would travel to Scotland, Ireland, and England on a sketching tour before embarking on any formal education, writing letters home to chart his progress and his adventures. Read more

The great Hungarian filmmaker Jancsó Miklós (or Miklós Jancsó, as he is known in the West) died peacefully in his sleep on January 31, 2014. Mehelli Modi, who has released excellent DVD editions of some of his films on Second Run in the U.K. (and has more recently brought out a Blu-Ray of his remarkable 1974 Electra, My Love), emailed me a couple of weeks later, asking, on behalf of Jancsó’s sons Nyika and David, if I could write something to be read at his memorial service on February 22. Here is what I sent back. — J.R.

It would hardly be an exaggeration to say that I regard Jancsó Miklós as one of the great lost continents of world cinema, especially outside Hungary — and largely, I suspect, because Hungarian history, which forms a major part of his oeuvre, is another lost continent from the vantage point of the West. With the possible exception of Sergei Eisenstein, I suspect that Jancsó remains the supreme example of a film artist who views history as a multilayered and passionate form of pageantry, something to be sung and danced, by the camera as well as by the actors, and, speaking more figuratively, by the audience. Read more

From the Summer 2018 issue of Cinema Scope. — J.R.

1. Second Thoughts First

In the introduction to my forthcoming collection Cinematic Encounters: Interviews and Dialogues, I make the argument that although Truffaut’s book-length interview with Hitchcock doesn’t qualify precisely as film criticism, it nonetheless had a decisive critical effect on film taste. By the same token, on Criterion’s very welcome Blu-ray edition of Frank Borzage’s Moonrise (1958), Peter Cowie’s interview with Borzage critic/biographer Hervé Dumont — whose book on the director should be shelved and considered alongside Chris Fujiwara’s book for the same publisher (McFarland) on Jacques Tourneur — primed me perfectly for my second look at this masterpiece, and made it register far more powerfully this time. It certainly performs this task better than Philip Kemp’s accompanying essay, which, in spite of much useful information, falters in its insistence on framing Moonrise through the lens of film noir, and even more when, while rightly praising the character of Rex Ingram’s Mose, the author remarks that “It would be hard to think of another American film of the period where a black man acts as adviser and mentor to a white Southerner.” It’s not so hard, really, if one thinks of Clarence Brown’s Intruder in the Dust (1949) and/or Tourneur’s Stars in My Crown (1950); and it’s even quite easy if, following Dumont’s lead on Moonrise, one regards the Tourneur masterpiece neither as a noir (a lazy escape hatch) nor as a western (as Jacques Lourcelles does), but as a discreet form of German Expressionism, implicitly favouring thoughtful philosophy and metaphysics over simple gloom and doom. Read more