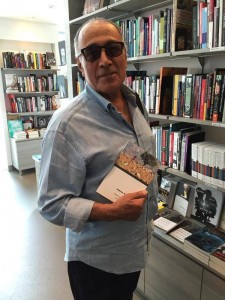

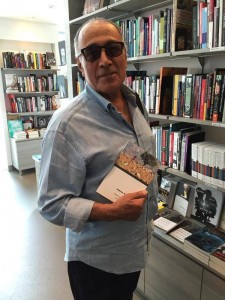

Written in late July, 2014 for this recently published volume. — J.R.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM: Having by now covered practically all of the films of Abbas Kiarostami between us — starting with our book about him published in 2003, which dealt with all the films up through 10 (2002), and then continuing with further articles and dialogues since then, all the way up through Like Someone in Love (2012) -– it’s hard to know what we can add in the form of a Preface to the Persian translation of all of the above. Broadly speaking, I suppose one could say that over the past decade, Kiarostami has shifted from being an arthouse director to being a sort of gallery artist who worked in both film and still photography before finally, in more international and less Iranian terms, becoming an arthouse director again. Does this overall description of his evolution strike you as being accurate? And do you think Kiarostami has gained or lost anything in the process?

MEHRNAZ SAEED-VAFA: Your description sounds accurate to me, and I think Kiarostami has definitely gained something. He’s made several shorts and features going in different directions and styles that continue to challenge the expectations of his fans and followers. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 24, 1995). I must confess that I’m immensely grateful that I no longer remember anything more than a stray detail or two about the dozen movies cited in the first paragraph, including the film under review. — J.R.

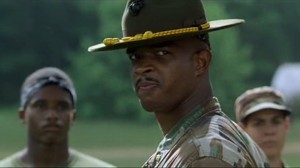

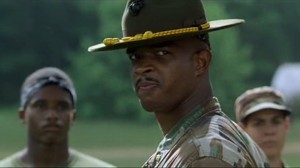

Major Payne *

Directed by Nick Castle

Written by Dean Lorey, Damon Wayans, and Gary Rosen

With Wayans, Karyn Parsons, Steven Martini, Andrew Harrison Leeds, Joda Blaire-Hershman, Stephen Coleman, and Orlando Brown.

It’s hard to remember when the mainstream releases have been as dismal as the offerings of the past few weeks. Admittedly, I haven’t seen everything, so it’s possible I missed the odd trick or two. But the rewards of The Quick and the Dead, Federal Hill, The Walking Dead, Losing Isaiah, Outbreak, Shallow Grave, Tall Tale, Circle of Friends, Bye Bye, Love, Candyman: Farewell to the Flesh, Muriel’s Wedding, and Major Payne have been so paltry that I’ve been reluctant to search out further punishment. If there’s an element that unites this disparate dozen, it’s an absence of characters — an absence stemming from a lack of consistent vision of what characters are supposed to be. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (June 2, 2000).

On October 5, 2014, I had the pleasure of introducing The Sandwich Man at the Museum of the Moving Image’s exhaustive Hou retrospective in Astoria. My late friend Gilberto Perez came to the screening and we had dinner afterwards; it was the last time I ever saw him.

For a Turkish translation of this article, go here. — J.R.

Films by Hou Hsiao-hsien

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

We are what we pretend to be, so we must be careful about what we pretend to be. — Kurt Vonnegut Jr., Mother Night

How significant is it that neither of the two greatest working narrative filmmakers is fluent in English? Not very. But it might be logical. After all, most of the people in the world, including those in Iran and Taiwan, don’t speak English, even though that places them, in American eyes, in the margins, outside even the on-line global culture.

If being in the margins means being in the majority, it stands to reason that Abbas Kiarostami and Hou Hsiao-hsien, as chroniclers of what’s happening on the planet at the moment, should both be poet laureates of the sticks — though they don’t have much in common beyond a taste for filming in long shot, pioneering direct sound recording in their national cinemas (in both cases to honor the speech patterns of nonprofessional actors), and a general sense of philosophical detachment. Read more