From the Chicago Reader (May 7, 1999). — J.R.

Dr. Akagi Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed by Shohei Imamura

Written by Imamura and Daisuke Tengan

With Akira Emoto, Kumiko Aso, Jyuro Kara, Jacques Gamblin, and Masanori Sera.

If you saw Abbas Kiarostami’s Taste of Cherry you may recall a joke told by the Turkish taxidermist: When a man complains to a doctor that every part of his body hurts — “When I touch my chest, that hurts; when I touch my arm and my leg, my arm and my leg hurt” — the doctor suggests that what’s actually bothering him is an infected finger. Similarly, when we think about Japan we may be prone to confuse what we’re pointing at with the finger that’s doing the pointing — especially given how much of a role our country played in the rebuilding of Japan after the war. (Perhaps significantly, scant attention is paid to Japanese movies about — and made during — the American occupation, such as Yasujiro Ozu’s devastating and uncharacteristic A Hen in the Wind and Kenji Mizoguchi’s Utamaro and His Five Women, a period film whose theme of artistic imprisonment is clearly addressed to his contemporaries.)

Even when it comes to Japan before the occupation, we may tend to overlook or misinterpret American influences, seeing them instead as Japanese traits. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (December 19, 2003). — J.R.

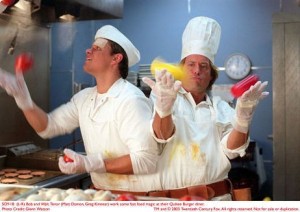

Stuck on You

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Bobby and Peter Farrelly

Written by Bobby and Peter Farrelly, Charles B. Wessler, and Bennett Yellin

With Matt Damon, Greg Kinnear, Eva Mendes, Wen Yann Shih, Cher, Seymour Cassel, Griffin Dunne, and Meryl Streep.

One of my all-time favorite Japanese movies is Yasuzo Masumura’s A Wife Confesses (1961), which I’ve been able to see only once, in Tokyo with a live English translation. It’s a courtroom thriller about a young widow who’s being tried for her part in the death of her abusive older husband while they were mountain climbing, and it hinges on the haunting question of what she was thinking when she made the split-second decision to cut the rope connecting the two of them. She was attached at the other end of the rope to an attractive young man who had business ties to her husband and with whom she was in love, and she had to cut one of the men loose to prevent all three of them from plummeting to their deaths.

The story is a tragic allegory about the interdependence of individuals in Japanese society and how this conflicts with individual choice and desire, and I can’t imagine it being remade in this country, where the rightness of the heroine’s choice would more likely be regarded as self-evident. Read more

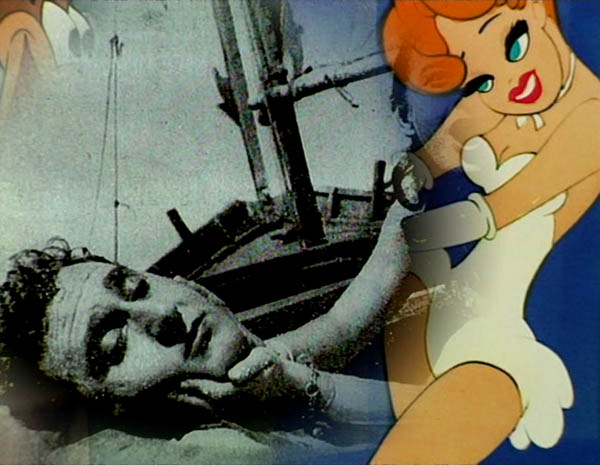

From the Chicago Reader (July 16, 1993). For a more detailed commentary on the Histoire(s), including Godard’s own input, go here. — J.R.

HISTOIRE(S) DU CINÉMA **** (Masterpiece)

Directed and written by Jean-Luc Godard

With Jean-Luc Godard.

MONTPARNASSE 19 ** (Worth seeing)

Directed and written by Jacques Becker

With Gerard Philipe, Lilli Palmer, Anouk Aimee, Gerard Sety, Lila Kedrova, Lea Padovani, Denise Vernac, and Lino Ventura.

If you want to be “up to the minute” about cinema, there’s no reason to be concerned that it’s taken four years for Jean-Luc Godard’s ambitious video series to reach Chicago. After all, James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, the artwork to which Histoire(s) du cinéma seems most comparable, written between 1922 and 1939, was first published in 1939, but if you started to read it for the first time this week, you’d still be way ahead of most people in keeping up with literature. For just as Finnegans Wake figuratively situates itself at some theoretical stage after the end of the English language as we know it — from a vantage point where, inside Joyce’s richly multilingual, pun-filled babble, one can look back at the 20th century and ask oneself, “What was the English language?” Read more