I’m a member of PEN, and Nick Burd, their Literary Awards Program Manager, just forwarded to me the following note from Barbara Epler at New Directions:

Dear Jonathan Rosenbaum,

I was reading through PEN’s very interesting “What are we missing?” forum, and saw your SÁTÁNTANGÓ suggestion, and just wanted to say we are waiting on the delivery of its [English] translation by the great George Szirtes, eagerly waiting, and will publish it as soon as we can. (We already have his translations of László [Krasznahorkai]’s THE MELANCHOLY OF RESISTANCE and WAR & WAR.)

I thought you’d be interested — and, by the way, we are always interested in hearing suggestions from readers who seem on our wave-length so if you have more ideas, please let me know.

All the best,

Barbara Epler

New Directions

P.S. (from JR): THE MELANCHOLY OF RESISTANCE is the 1989 novel that served as the basis for Béla Tarr’s 2000 film WERCKMEISTER HARMONIES. And SÁTÁNTANGÓ (the film) has recently been released in a box set by Facets Video. [8/21/08] Afterword, 2012: The English translation of the novel has finally been published.

Read more

I’d read enough about this documentary, made over 11 years by Steven Sebring, to know not to expect a concert film. What I was less prepared for was the paradoxical view of my favorite punk star that emerges, making her seem like the ultimate postmodernist heroine — the edgy outlaw that, to all appearances, has never been in even modest rebellion against any part of her family, and modulates from angry iconoclast to contented Detroit housewife and back again with scarcely a bump. (At one point she avows that her principal claim to being a taboo-breaker as a child-rearing launderer is that she doesn’t use bleach.) It seems fairly evident that she’s very much in control of her own image here, and that image manages to encompass a sense of a rock star’s glamor while suggesting that she’s never shampooed her hair even once in her life.

Maybe the source of my confusion is her unusual capacity to shift back and forth repeatedly between ultra-theatricality and mundanity, which made the only concert of hers I’ve ever attended, in London in the mid-70s, a little off-putting. One moment she’d be leading the audience like a Dionysian Joan of Arc; the next moment, she’d be sitting on the floor cross-legged, apparently oblivious to the same audience, while playing idly with her guitar as if it were a kitten rather than a musical instrument. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 16, 2008). — J.R.

Screenwriter Charlie Kaufman (Being John Malkovich, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind) makes his directorial debut with this feature, but it seems more like an illustration of his script than a full-fledged movie, proving how much he needs a Spike Jonze or a Michel Gondry to realize his surrealistic conceits. Tortured and torturous, it centers on a theater director from Schenectady (Philip Seymour Hoffman) who wins a MacArthur Fellowship but whose wife (Catherine Keener) leaves him; in response he tries to create a play that will represent his entire life experience, building a replica of New York City inside a warehouse. The usually resourceful Hoffman can’t sustain interest even after developing a receding hairline to make him resemble Jack Nicholson, and the other able players — Samantha Morton, Michelle Williams, Emily Watson, Dianne Wiest, Tom Noonan, Hope Davis, and Jennifer Jason Leigh — mainly tread water. R, 124 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

UNE SALE HISTOIRE/A DIRTY STORY (Jean Eustache, 1977, 28 minutes [35mm] + 22 minutes [16mm]); LE JARDIN DES DÉLICES DE JÉRÔME BOSCH/ HIERONYMOUS BOSCH’S “THE GARDEN OF EARTHLY DELIGHTS” (Jean Eustache, 1979, 34 minutes [16mm]). Playing at the Gene Siskel Film Center with Eustache’s ALIX’S PHOTOS (1980, 18 minutes, 35mm) on May 25 at 3 PM.

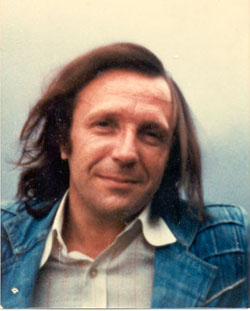

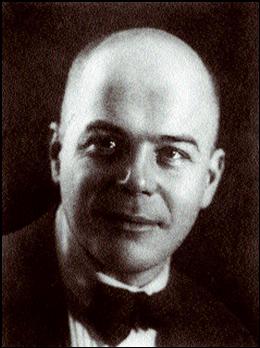

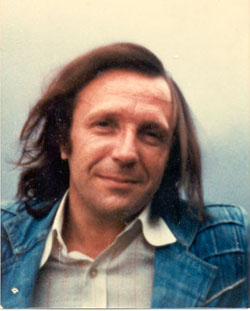

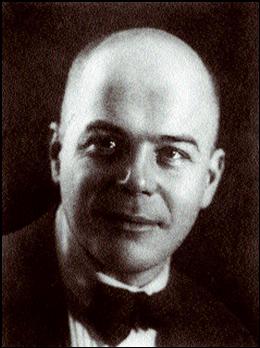

Jean Eustache (1938-81, above photo) was clearly obsessed with remakes. Not only did he remake his 1968 documentary about his home town, LA ROSIÈRE DE PESSAC, in 1979; he also remade his 1977 documentary UNE SALE HISTOIRE twice—first as a fiction film, and then, less literally, as a documentary about Bosch’s “The Garden of Earthy Delights” two years later.

Let me explain. The first version of UNE SALE HISTOIRE, designed to be shown second, and shot in 16mm, features Jean-Noël Picq recounting a supposedly real-life “dirty” story to a group of people, mainly women (although also including Eustache himself, visible in the foreground of a couple of shots)—a tale about peering for hours through a hole in the wall of a café into the ladies room in order to watch the snatches of women seated on the toilet. (He calls the women’s snatches their “holes,” and the word trou is repeated incessantly throughout his monologue.) Read more

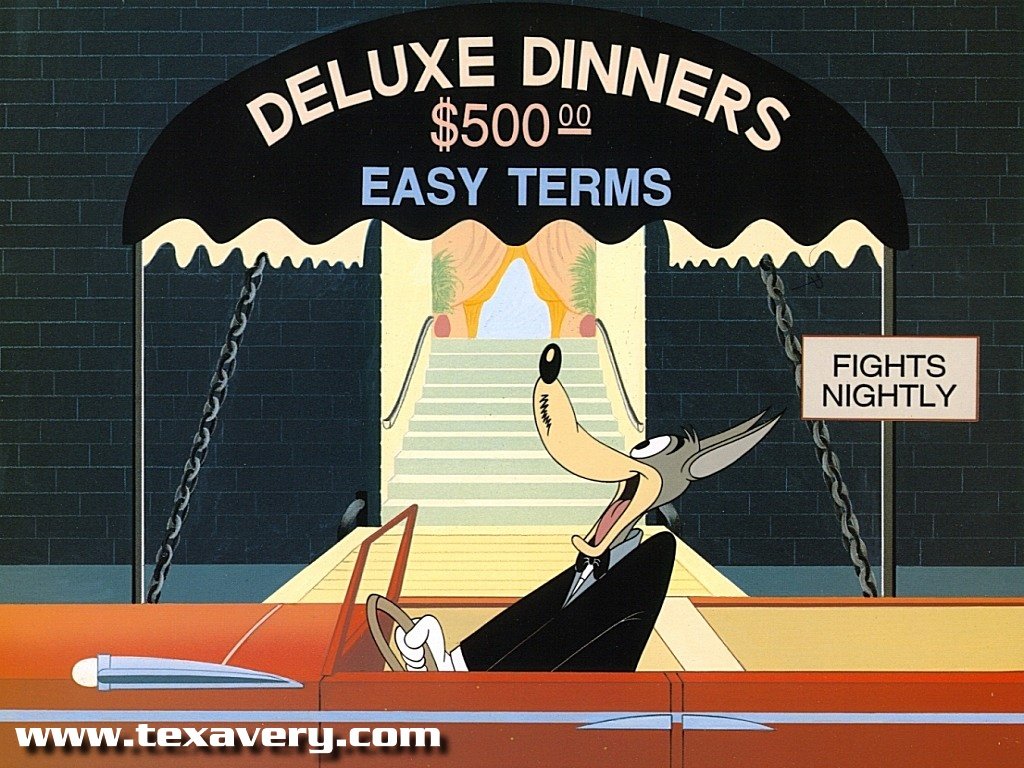

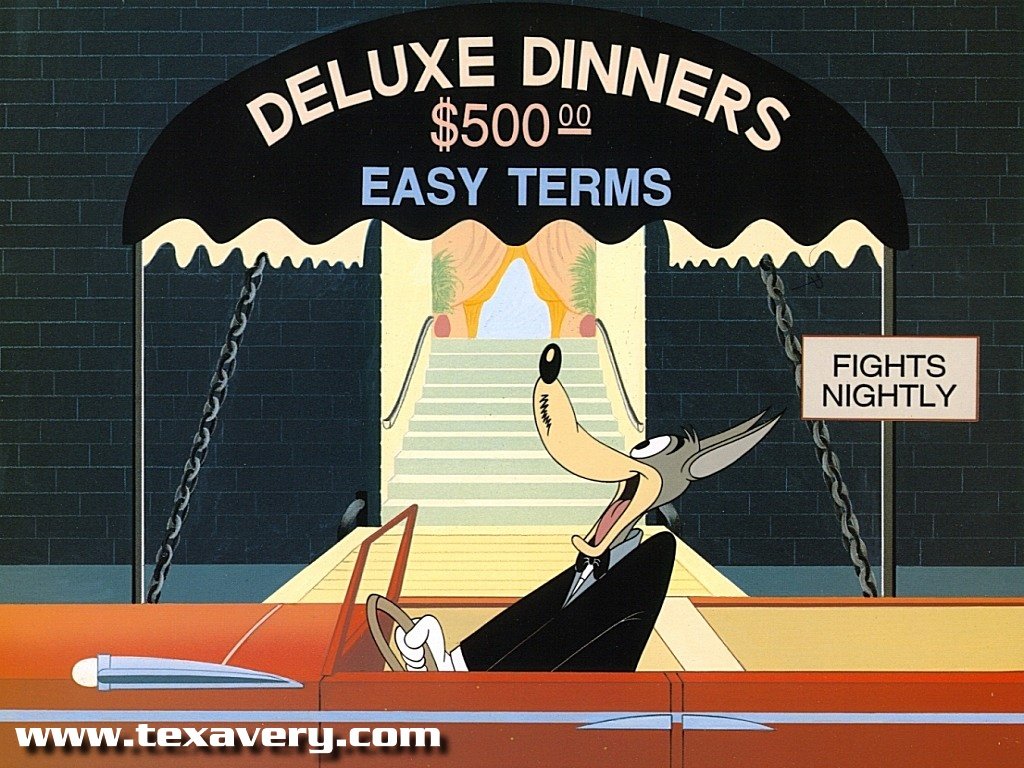

TEX AVERY: A UNIQUE LEGACY (1942-1955) by Floriane Place-Verghnes (Eastleigh, UK: John Libbey Publishing), 2006, 214 pp.

I love the last line in Dr. Place-Verghnes’ Acknowledgments -– a tactful understatement which demonstrates both that she wears her academic armor lightly and that she’s temperamentally suited to dealing with someone like Avery: “I reserve a particular sentiment for Warner Brothers Inc., without whom and their point-blank refusal to grant copyright authorisation, this volume would have contained multiple images from Tex Avery and others’ cartoons in support of the textual content.” (Actually, she does cheat a tad by reproducing or at least imitating a classic Avery image on the book’s cover–two giant bulging eyeballs as they appear in one of the Wolf cartoons.)

It’s too bad she didn’t publish this book online–in which case I presume she would have had as little difficulty in illustrating the graphic brilliance of Avery as I’m having here by scavenging diverse items from the Internet. For starters, here are three more characteristic samples:

One of the more interesting challenges in viewing Avery’s vintage MGM work is learning how to process various aspects of their racism and sexism without overlooking their good-humored humanity or drowning in political correctness. Read more

As evidenced by everything from Trouble the Water to WALL-E to Wendy and Lucy, the disastrous effects of unchecked capitalism may be the most urgent contemporary theme in movies. The brilliantly innovative Chinese filmmaker Jia Zhang-ke (Platform, The World, Still Life) has been able to create works of historical relevance partly because he considers this theme from the vantage point of a socialism that, far from being theoretical, is part of a complex lived experience. This beautiful and challenging documentary looks at a military factory in Chengdu that’s shutting down to make way for a luxury apartment complex, and in interviewing five former workers and three fictional characters (played by Joan Chen, Lu Liping, and his frequent collaborator Zhao Tao), Jia manages to convey how three generations are affected by this change. In Mandarin with subtitles. 112 min. (JR) Read more

DOUGLAS SIRK COLLECTION (ALL I DESIRE, THERE’S ALWAYS TOMORROW & INTERLUDE), German DVD box set.

My favorite Sirk film, SCHLUSSAKKORD (FINAL ACCORD, 1936), has yet to come out on DVD anywhere, but this attractively put together German box set of three digitally restored 50s Hollywood features, purchased via German Amazon, does include the similarly titled DER LETZTE AKKORD (INTERLUDE, 1956), which turns out to be the only stinker in the bunch, despite the fact that it’s in color and CinemaScope. (Even a diehard fan like Fassbinder admitted this kitschy item is “a hard film to get into”.) The other two -– both excellent, complexly nuanced, doom-ridden and hard-as-nails melodramas in black and white -– are the pictures Sirk made with Barbara Stanwyck, in 1953 and 1955 respectively, each of which charts her character’s belated and troubled small-town homecoming. In the first, set around the turn of the century, she’s a not-very-successful stage actress returning to visit her family in Wisconsin; in the second she’s a divorced and successful clothes designer looking up her one-time boyfriend (Fred MacMurray), who now has a family of his own (including a somewhat miscast Joan Bennett). Both are about as bleak as movies can get -– notwithstanding ALL I DESIRE’s studio-imposed happy ending, which is impossible to believe in anyway. Read more

From Cinema Scope issue issue 60, Fall 2014. — J.R.

DVD AWARDS 2014

XI edition (Il Cinema Ritrovato, Bologna)

Jurors: Lorenzo Codelli, Alexander Horwath, Mark McElhatten, Paolo Mereghetti and Jonathan Rosenbaum, chaired by Peter von Bagh

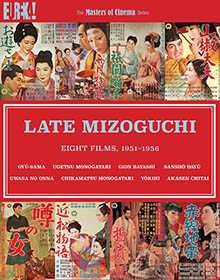

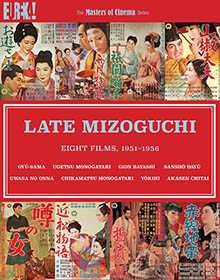

BEST SPECIAL FEATURES ON BLU-RAY:

Late Mizoguchi – Eight Films, 1951-1956 (Eureka Entertainment). The publication of eight indisputable masterpieces in stellar transfers on Blu-ray is a cause for celebration. If Eureka is not exclusive in offering these individual titles, what makes this collection especially praiseworthy and indispensable is the scholarship, imagination and care that went into the accompanying 344-page booklet. Over 60 rare production stills are included, many featuring Mizoguchi at work. Striking essays by Keiko I. McDonald, Mark Le Fanu, and Nakagawa Masako are anthologized along with extensively annotated translations of some of the key sources of Japanese literature that inspired some of Mizoguchi’s late films. The volume closes with tributes to the great director written by Tarkovsky, Rivette, Godard, Straub, Angelopoulos, Shinoda, and others. Tony Rayns provides spoken essays and some full-length commentaries.

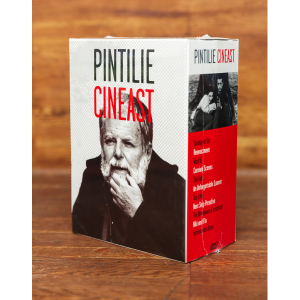

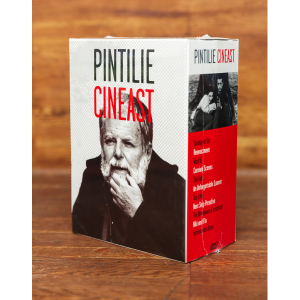

BEST SPECIAL FEATURES ON DVD:

Pintilie, Cineast (Transilvania Films). An impeccable collection devoted to eleven films by an important and neglected maverick Romanian filmmaker, masterful and acerbic, with invaluable contextualizing extras concerning his life, work, and career drawn from ten separate sources. Read more

This is a very short and very early article by Roland Barthes, one of his “Mythologies” that remains uncollected in English, that I translated in 1982, originally so it could be run with an article of mine, “Barthes & Film: 12 Suggestions,” that I published in Sight and Sound — although it wound up not appearing there due to a lack of space. (I did, however, use some extracts from it in an article I did for the same magazine two years later about Gentlemen Prefer Blondes; both of these articles are reprinted in my first collection, Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism.) Many years later, in 1999, James Morrison asked me if he could post it on the Internet, and you can still access it, along with an essay of his about it, here. — J.R.

-

- If, for lack of the proper technical background, I can’t define Henri Chrétien’s [anamorphic] process, at least I can judge its effects. They are, in my opinion, surprising. The broadening of the image to the dimensions of binocular vision should fatally transform the internal sensibility of the filmgoer. In what respect? The stretched-out frontality becomes almost circular; in other words, the ideal space of the great dramaturgies.

Read more

LITERATURE AND CINEMATOGRAPHY by Viktor Shklovsky (Champaign and London: Dalkey Archive Press), 2008, 74 pp. Translated by Irina Masinovsky; Introduction by Richard Sheldon.

What’s unexpected about this early theoretical foray by the father of Russian Formalism (1893-1984), first published in 1923 and now appearing in English for the first time, is that it conveys pretty much the same emotion underlying “Moviegoer,” an essay by William Styron first published (in French, in the newspaper Le Figaro) in 1983 and now recently making its first appearance in English in Styron’s HAVANAS IN CAMELOT (see below): the anxiety of a literary writer feeling threatened by movies. (The same anxiety, incidentally, crops up periodically in other essays by Styron in the same book: in “`I’ll Have To Ask Indianapolis–’”, for instance, Styron records his consternation at receiving a dissertation in the mail entitled “SOPHIE’S CHOICE: a Jungian Perspective” -– a study containing the following explanatory footnote: “Where the movie was vague I referred to the book, SOPHIE’S CHOICE, for clarification.”)

Shklovsky: “If it is impossible to express a novel in words other than those in which it has been written, if it is impossible to change the sounds of a poem without changing its essence, then it is even more impossible to replace words with a grey-and-black shadow flashing on the screen.” Read more

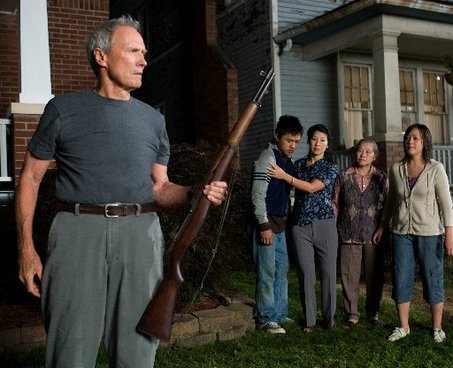

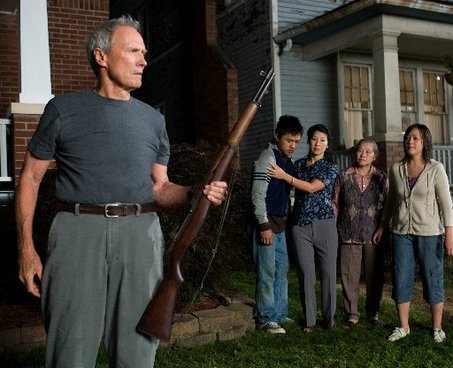

I’m still doping out what I think of The Curious Case of Benjamin Button and Gran Torino, although I did see the latter in time and liked it enough to slip into some of my end-of-the-year ten-best lists. (Since my thoughts and inclinations tend to change over time, I’m reluctant to keep recycling the same list every time I’m asked for one.)

Having just seen Benjamin Button, I still don’t know whether I might have included it in any of my lists, but I have to admit that I suspect I already prefer it to all of Fincher’s other films, with the possible exception of Se7en. It took me a while to warm to the weird premise and some of the grotesqueries it involves, but I think part of what impresses me is how nervy it is in playing out the poetry of the conceit for all that it’s worth and letting all the social-historical elements—from two world wars to Hurricane Katrina (and not overlooking the degree to which it sidesteps all the racial issues)–take a back seat to the love story. It’s also more impressive to me visually than Fincher’s other works. Whatever one concludes about the story and all its ramifications, he certainly knows how to fill a frame. Read more

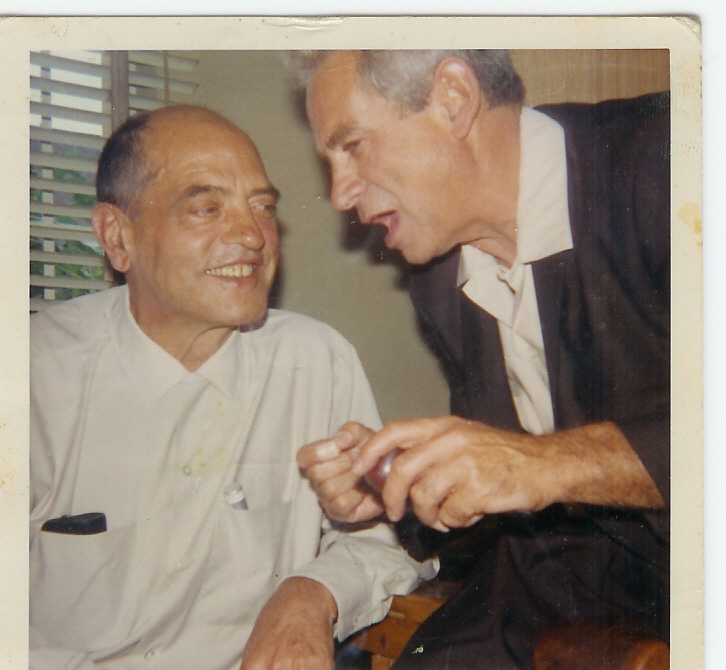

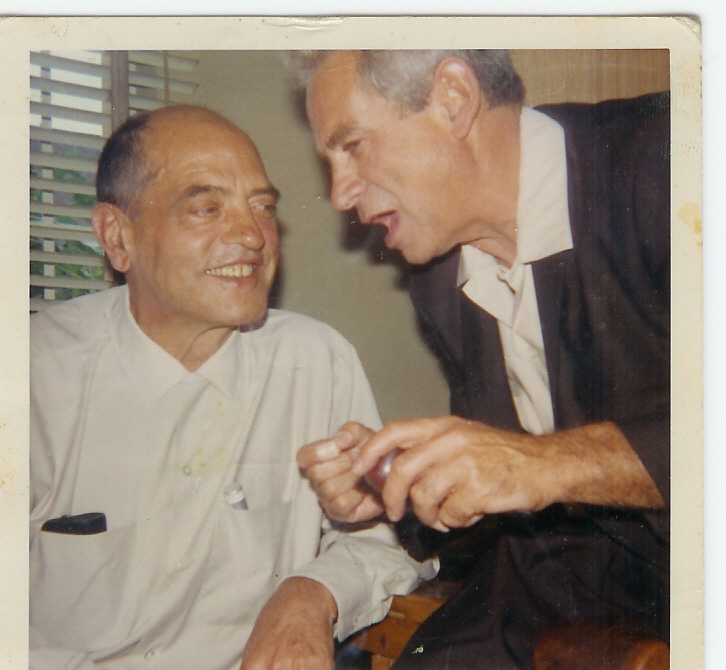

Christa Fuller, who took this picture in 1967 in Buñuel’s house in Mexico City, has invited me to place it here; it shows Buñuel with her late husband, Sam. The first time I ever met Sam, in the summer of 1980, I interviewed him at the Plaza Hotel in New York about The Big Red One for the Soho News. He was being courted at the time by Serge Silberman about possibly directing a French best seller called The Tunnel, and Sam let out a rebel-style holler when I said something like, “Isn’t that Buñuel’s producer?” “Yaaah! That why I had a hard-on for him, boy, he puts all the loot up for Buñuel, and I love that man.” (8/17/08)

Read more

TOMORROW IS NOW by Ernest Borneman (London: Neville Spearman), 1959, 205 pp. There are few careers more fascinating and multifaceted than that of Ernest Borneman (1915-1995), a German-born psychotherapist and non-fiction writer who also wrote several novels (all in English), and whose other professions at various stages in his career included playwright, cameraman, screenwriter, writer for TV and radio, film director, prolific journalist, and jazz musician. I’ve tried to encapsulate a few things about him, including his work with Orson Welles and his discovery of Eartha Kitt, in a long footnote on pp. 3-4 of my book MOVIE WARS, where I quote from a brilliant 1947 essay of his, “The Public Opinion Myth,” in order to counter many of the assumptions underlying the test-marketing of movies. I’ve now read only two of his novels, all of which are out of print: THE FACE ON THE CUTTING-ROOM FLOOR (1937), his first and best known (though published under the pseudonym of Cameron McCabe), a flavorsome murder mystery that I treasure mainly for its dialogue as well as its 24-page Afterword about Borneman–written by the book’s editors, though containing a lot of interview material and a letter from Borneman, dating from 1979 and 1981, respectively. Read more

Recommended Reading:

CHARLES FORT: THE MAN WHO INVENTED THE SUPERNATURAL by Jim Steinmeyer, New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Penguin, 332 pp.

NIGHT WRAPS THE SKY: WRITINGS BY AND ABOUT MAYAKOVSKY, edited by Michael Almereyda, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008, 272 pp.

Technically these are a biography and an anthology, but both are in effect delightful samplers of the work of two very singular and controversial men who were roughly contemporaries, although they were born 19 years apart: Charles Fort (1874-1932) and Vladimir Mayakovsky (1893-1930). I’m far from completing either book at this point, but both make for very pleasurable summer reading.

Fort was a late bloomer, especially regarding his public profile, which essentially consisted of the last four of his five published books–The Book of the Damned (1919), New Lands (1923), Lo! (1931), and Wild Talents (1932), all very witty, imaginative, and provocative forays into debunking science. These were preceded only by several short stories published only in magazines and a 1909 novel that has never been reprinted, as well as some other creative non-fiction, all unpublished, that Steinmeyer quotes from liberally. Steinmeyer is a specialist in stage magic with whom I once had the pleasure of doing a lengthy phone interview. Read more

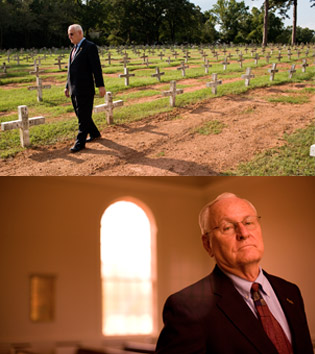

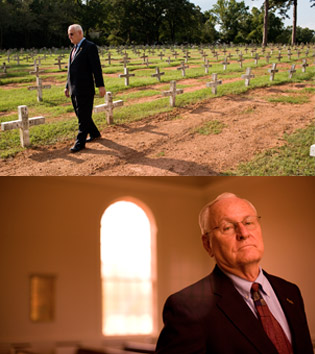

AT THE DEATH HOUSE DOOR (Steve James and Peter Gilbert, 2008, 94 min .)

This remarkable Katemquin documentary is showing at 8 PM tonight on the IFC channel (I saw it last night, at a free public screening), but if you miss it there, you’ll have plenty of other chances to see it–you can even screen it online. It wouldn’t quite do the film justice to say that it’s about capital punishment and miscarriages of justice in Huntsville, Texas, although these topics are certainly part of its fabric. It’s really a character study of Carroll Pickett, a quiet, undemonstrative man who served as the death house chaplain for over 95 executions, including the world’s first lethal injection, and gradually went from believing to disbelieving in capital punishment in the process. You might say that he’s someone who discovered the truth about his activity the hard way, which may also be the best way.

By the same token, as I believe Peter Gilbert pointed out at the screening I attended, this isn’t a “political” film in the usual sense, and it doesn’t preach, even though it’s about a preacher. Steve James and Gilbert put it across with so much power because they know how to tell stories, as their previous films–including James’s HOOP DREAMS, STEVIE, and REEL PARADISE, and Gilbert’s VIETNAM: LONG TIME COMING–amply demonstrate. Read more