LITERATURE AND CINEMATOGRAPHY by Viktor Shklovsky (Champaign and London: Dalkey Archive Press), 2008, 74 pp. Translated by Irina Masinovsky; Introduction by Richard Sheldon.

What’s unexpected about this early theoretical foray by the father of Russian Formalism (1893-1984), first published in 1923 and now appearing in English for the first time, is that it conveys pretty much the same emotion underlying “Moviegoer,” an essay by William Styron first published (in French, in the newspaper Le Figaro) in 1983 and now recently making its first appearance in English in Styron’s HAVANAS IN CAMELOT (see below): the anxiety of a literary writer feeling threatened by movies. (The same anxiety, incidentally, crops up periodically in other essays by Styron in the same book: in “`I’ll Have To Ask Indianapolis–’”, for instance, Styron records his consternation at receiving a dissertation in the mail entitled “SOPHIE’S CHOICE: a Jungian Perspective” -– a study containing the following explanatory footnote: “Where the movie was vague I referred to the book, SOPHIE’S CHOICE, for clarification.”)

Shklovsky: “If it is impossible to express a novel in words other than those in which it has been written, if it is impossible to change the sounds of a poem without changing its essence, then it is even more impossible to replace words with a grey-and-black shadow flashing on the screen.” Read more

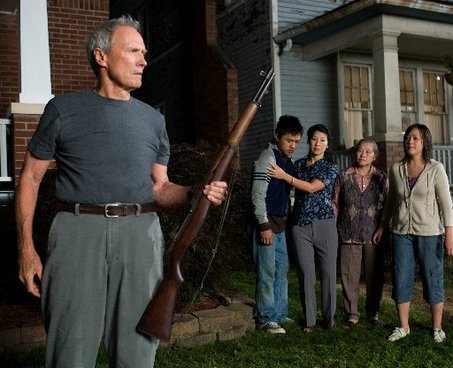

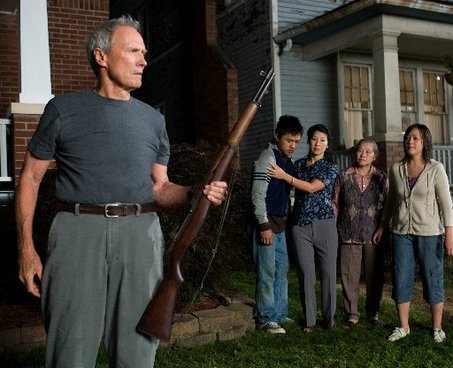

I’m still doping out what I think of The Curious Case of Benjamin Button and Gran Torino, although I did see the latter in time and liked it enough to slip into some of my end-of-the-year ten-best lists. (Since my thoughts and inclinations tend to change over time, I’m reluctant to keep recycling the same list every time I’m asked for one.)

Having just seen Benjamin Button, I still don’t know whether I might have included it in any of my lists, but I have to admit that I suspect I already prefer it to all of Fincher’s other films, with the possible exception of Se7en. It took me a while to warm to the weird premise and some of the grotesqueries it involves, but I think part of what impresses me is how nervy it is in playing out the poetry of the conceit for all that it’s worth and letting all the social-historical elements—from two world wars to Hurricane Katrina (and not overlooking the degree to which it sidesteps all the racial issues)–take a back seat to the love story. It’s also more impressive to me visually than Fincher’s other works. Whatever one concludes about the story and all its ramifications, he certainly knows how to fill a frame. Read more

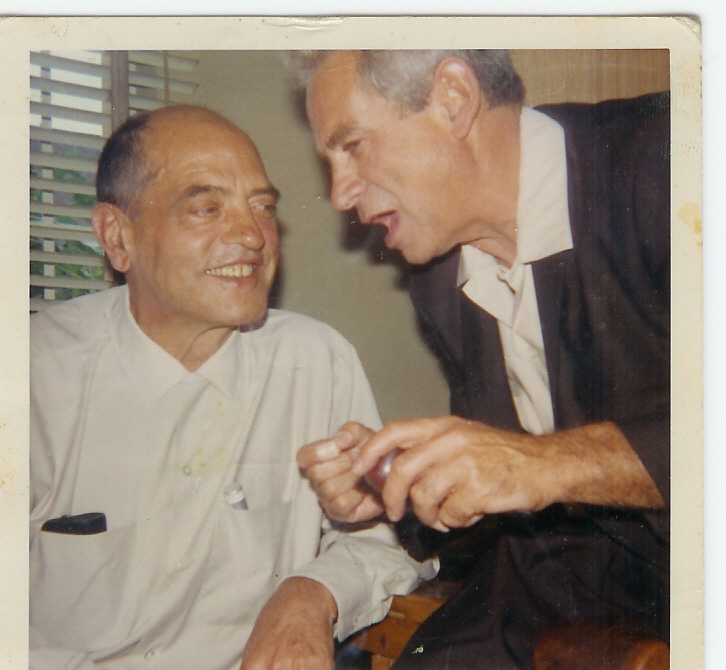

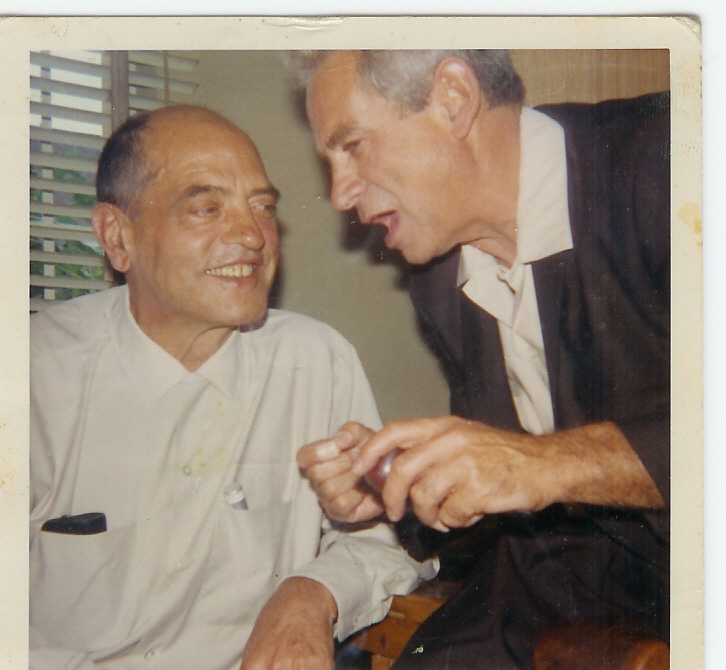

Christa Fuller, who took this picture in 1967 in Buñuel’s house in Mexico City, has invited me to place it here; it shows Buñuel with her late husband, Sam. The first time I ever met Sam, in the summer of 1980, I interviewed him at the Plaza Hotel in New York about The Big Red One for the Soho News. He was being courted at the time by Serge Silberman about possibly directing a French best seller called The Tunnel, and Sam let out a rebel-style holler when I said something like, “Isn’t that Buñuel’s producer?” “Yaaah! That why I had a hard-on for him, boy, he puts all the loot up for Buñuel, and I love that man.” (8/17/08)

Read more