TOMORROW IS NOW by Ernest Borneman (London: Neville Spearman), 1959, 205 pp. There are few careers more fascinating and multifaceted than that of Ernest Borneman (1915-1995), a German-born psychotherapist and non-fiction writer who also wrote several novels (all in English), and whose other professions at various stages in his career included playwright, cameraman, screenwriter, writer for TV and radio, film director, prolific journalist, and jazz musician. I’ve tried to encapsulate a few things about him, including his work with Orson Welles and his discovery of Eartha Kitt, in a long footnote on pp. 3-4 of my book MOVIE WARS, where I quote from a brilliant 1947 essay of his, “The Public Opinion Myth,” in order to counter many of the assumptions underlying the test-marketing of movies. I’ve now read only two of his novels, all of which are out of print: THE FACE ON THE CUTTING-ROOM FLOOR (1937), his first and best known (though published under the pseudonym of Cameron McCabe), a flavorsome murder mystery that I treasure mainly for its dialogue as well as its 24-page Afterword about Borneman–written by the book’s editors, though containing a lot of interview material and a letter from Borneman, dating from 1979 and 1981, respectively. Read more

Recommended Reading:

CHARLES FORT: THE MAN WHO INVENTED THE SUPERNATURAL by Jim Steinmeyer, New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Penguin, 332 pp.

NIGHT WRAPS THE SKY: WRITINGS BY AND ABOUT MAYAKOVSKY, edited by Michael Almereyda, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008, 272 pp.

Technically these are a biography and an anthology, but both are in effect delightful samplers of the work of two very singular and controversial men who were roughly contemporaries, although they were born 19 years apart: Charles Fort (1874-1932) and Vladimir Mayakovsky (1893-1930). I’m far from completing either book at this point, but both make for very pleasurable summer reading.

Fort was a late bloomer, especially regarding his public profile, which essentially consisted of the last four of his five published books–The Book of the Damned (1919), New Lands (1923), Lo! (1931), and Wild Talents (1932), all very witty, imaginative, and provocative forays into debunking science. These were preceded only by several short stories published only in magazines and a 1909 novel that has never been reprinted, as well as some other creative non-fiction, all unpublished, that Steinmeyer quotes from liberally. Steinmeyer is a specialist in stage magic with whom I once had the pleasure of doing a lengthy phone interview. Read more

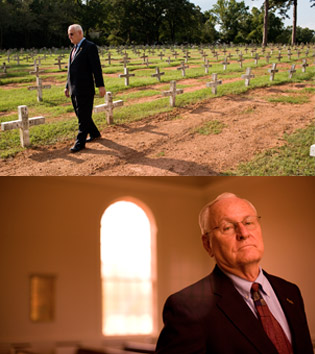

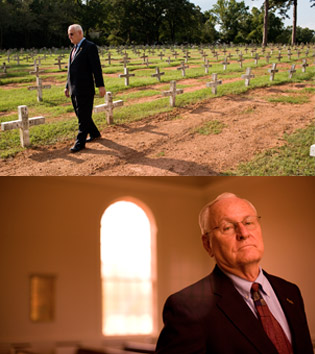

AT THE DEATH HOUSE DOOR (Steve James and Peter Gilbert, 2008, 94 min .)

This remarkable Katemquin documentary is showing at 8 PM tonight on the IFC channel (I saw it last night, at a free public screening), but if you miss it there, you’ll have plenty of other chances to see it–you can even screen it online. It wouldn’t quite do the film justice to say that it’s about capital punishment and miscarriages of justice in Huntsville, Texas, although these topics are certainly part of its fabric. It’s really a character study of Carroll Pickett, a quiet, undemonstrative man who served as the death house chaplain for over 95 executions, including the world’s first lethal injection, and gradually went from believing to disbelieving in capital punishment in the process. You might say that he’s someone who discovered the truth about his activity the hard way, which may also be the best way.

By the same token, as I believe Peter Gilbert pointed out at the screening I attended, this isn’t a “political” film in the usual sense, and it doesn’t preach, even though it’s about a preacher. Steve James and Gilbert put it across with so much power because they know how to tell stories, as their previous films–including James’s HOOP DREAMS, STEVIE, and REEL PARADISE, and Gilbert’s VIETNAM: LONG TIME COMING–amply demonstrate. Read more