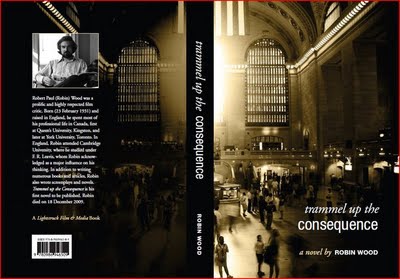

Now that I’ve finally read Robin Wood’s fascinating posthumous novel, an odd thriller involving amnesia, I’m pleased to report that it’s much better than I expected it to be, both as a page-turner and as what I would describe as a critic’s novel — even though the latter quality only became fully clear to me in the book’s closing pages.

The story as a whole can be described as a shotgun marriage or as a conversation — or perhaps as some of both — between a model of prose fiction that is literary, high- modernist, and intellectual and another model that is nonliterary, populist, and nonintellectual. These models and positions are represented by the novel’s two leading characters, a man and a woman respectively, the latter of whom is the story’s principal narrator and thus represents Wood’s own preferred position. It would be difficult to say much more about this without introducing spoilers — an especially heinous crime according to the nonintellectual model, and one that should clearly be avoided when it comes to the gradual revelations in this plot — but the degree to which the story as a whole represents a running debate between these positions reflects many of Wood’s own positions and tastes as a critic, which ran all the way from modernist art films to exploitation horror films — both of which are reflected, in different ways, in Trammel Up the Consequence.