Published by DVD Beaver in August 2006. — J.R.

Even though I don’t have much of a head for science, and even though I agree with the field’s chief literary critic, Damon Knight, that “we have no negative knowledge” (meaning that we aren’t yet in a position to identify time travel as either science or non-science), I’d still maintain that the differences between science fiction and fantasy are important. (For Damon Knight’s criticism, see his superb though sadly long out-of-print collection In Search of Wonder.) Important enough, in any case, to make a list of favorite neglected SF movies distinct and separate from a list of neglected fantasy movies. So consider the following selection the first half of a two-part series.

French people tend to conflate SF and fantasy a little more readily than others do into a looser category known as fantastique which also manages to encompass Surrealism, some forms of satire and horror, comic strips, comic books, and graphic novels, among other things. But for the purposes of this particular exercise, credible extrapolations or fictions that at least pretend to have some relation to science —- by which I mean Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (admittedly a borderline case), The Nutty Professor, and The Incredible Shrinking Man, but not Pandora and the Flying Dutchman, The Tiger of Eschnapur, or Eyes Wide Shut —- qualify as science fiction. Read more

From the March 2016 issue of Artforum, where it appears under the title “Given Voice”. — J.R.

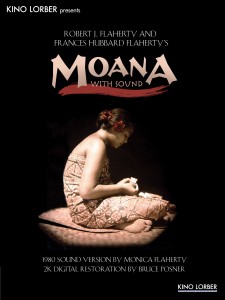

“Until recently,” wrote anthropologist Jay Ruby thirty-odd years ago, “the scholarship and popular press surrounding [Robert J.] Flaherty have tended toward two extremes—portraying him in mythical terms and ‘worshipping’ his films or debunking them as fakes and frauds and castigating him for a lack of social and political consciousness.” But the more balanced view of “Flaherty as a man of his time and culture” that Ruby saw succeeding these extremes still hasn’t fully taken hold, perhaps because the very meaning of the term “documentary” is still being debated. Even when we smile (or flinch) at some of Flaherty’s romantic conceptions, the comprehensive theoretical questions raised by his methods are ones we still can’t confidently say we’ve resolved.

“Documentary” was reportedly first used in English by the Scottish filmmaker John Grierson in a pseudonymous rave review of Flaherty’s second feature, Moana (1926). (Seeking to duplicate the success of Nanook of the North [1922], but in warmer climes, Flaherty set sail for the South Seas the following year, his entire family in tow, to shoot a film in Samoa.) Significantly, Grierson employed the novel term to register one of the film’s subordinate virtues: “Of course Moana, being a visual account of events in the daily life of a Polynesian youth, has documentary value,” he noted. Read more

I’m not sure why, but it seems like Woodstock has rarely gotten its due as a film. This review for the Chicago Reader ran on August 12, 1994, while I was working in New York on the New York Film Festival’s selection committee, and I recall that as a consequence I had to write and get most of this piece edited in Chicago well in advance. A little bit of it is recycled from the first paragraph of an article that I wrote for Grass: The Paged Experience, the 2001 book spinoff of Ron Mann ‘s documentary Grass — an update and revision of an article I wrote for High Times 15 years earlier. –J.R.

WOODSTOCK **** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Michael Wadleigh

With Richie Havens, Country Joe and the Fish, Joe Cocker, Sha Na Na, Arlo Guthrie, Joan Baez, Ten Years After, Santana, Sly and the Family Stone, Janis Joplin, the Who, John Sebastian, Jefferson Airplane, and Jimi Hendrix.

Michael Wadleigh’s epic documentary Woodstock (1970) has been reviewed often as an event, a symbol, and a cause, but it’s seldom been considered strictly as a movie; yet on this score it’s light-years beyond anything on the 60s counterculture ever released by a Hollywood studio. Read more