From the Chicago Reader (December 11, 1987). — J.R.

BELL DIAMOND

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Jon Jost

With Marshall Gaddis, Sarah Wyss, Terri Lyn Williams, Kristi Jean Hager, Dan Cornell, Hal Waldrup, Ron Hanekan, Alan Goddard, and Anne Kolesar.

The films I most eagerly look forward to will not be documentaries but works of pure fiction, played against, and into, and in collaboration with unrehearsed and uninvented reality. — James Agee

1. Jeff Doland (Marshall Gaddis), a Vietnam veteran in Butte, Montana, sits watching a baseball game on TV. Passing through the kitchen, he tells his wife Cathy (Sarah Wyss) that he’s going out to pick up some more beer. Cathy continues to unpack groceries and switches on a tiny toy train that runs in an elaborate loop on the kitchen table. Jeff returns with a six-pack and resumes watching TV. Cathy comes into the room and announces that she’s leaving him.

Bell Diamond‘s point of departure is about as ordinary and as banal as a plot can get — and not much happens after it, either. Neither Jeff nor Cathy is especially interesting or attractive or articulate, and the same can be said of the rest of the characters in this mainly eventless movie. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (August 1, 1987). — J.R.

Stanley Kubrick shares with Orson Welles and Carl Dreyer the role of the Great Confounder — remaining supremely himself while frustrating every attempt to anticipate his next move or to categorize it once it registers. This odd 1987 adaptation of Gustav Hasford’s The Short-Timers, with script-writing assistance from Michael Herr as well as Hasford, has more to do with the general theme of colonization (of individuals and countries alike) and the suppression by male soldiers of their female traits than with the specifics of Vietnam or the Tet offensive. Elliptical, full of subtle inner rhymes (for instance, the sound cues equating a psychopathic marine in the first part with a dying female sniper in the second), and profoundly moving, this is the most tightly crafted Kubrick film since Dr. Strangelove, as well as the most horrific; the first section alone accomplishes most of what The Shining failed to do. With Matthew Modine, Adam Baldwin, Vincent D’Onofrio, and R. Lee Ermey. R, 116 min. (JR)

Read more

From The Soho News (June 4, 1980). -– J.R.

Porcile (Pigpen)

A Film by Pier Paolo Pasolini

Bleecker Street Cinema, June 6

Salò

A Film by Pier Paolo Pasolini

Based on the 120 Days of Sodom

By the Marquis de Sade

Bleecker Street Cinema, June 11 and 12

“The problem with Pasolini,” a friend observed to me succinctly many years ago, “is that he wants to be fucked by Jesus and Marx at the same time.” A “pre-industrial,” populist poet and novelist from northern Italy whose relation to the Catholic Church and the Italian Communist Party were as passionately idiosyncratic as the homoeroticism of his films, Pasolini remains, nearly five years after his brutal murder, an indigestible provocateur in relation to our culture – someone who can be neither entirely absorbed nor totally rejected, but lingers like a troubling, irritating sore.

The recent and very belated release of his version of The Canterbury Tales (1972), the second part of his “trilogy of life” after The Decameron (1971), offers spectators a chance to catch more farting jokes than can probably be found in Blazing Saddles. His vastly superior version of The Arabian Nights (1974), which rounds off the trilogy –- probably the most sustained flirtation with paganism to be found in his work –- has yet to reach these provincial shores. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 13, 1990). I wish I could remember now which Reader staffer thought up the brilliant headline; it wasn’t me. — J.R.

PRETTY WOMAN

(Worthless)

Directed by Garry Marshall

Written by J.F. Lawton

With Richard Gere, Julia Roberts, Ralph Bellamy, Jason Alexander, Laura San Giacomo, Alex Hyde-White, and Hector Elizondo.

Having missed Pretty Woman when it opened more than three months ago, I figured I would just let it pass, but ultimately curiosity got the better of me. I’m not a big fan of either Richard Gere or Julia Roberts, but finally I had to see for myself how a movie that seemed to celebrate prostitution (at the same time it trashes prostitutes) — brought to us by the Disney studio, the same people responsible for such squeaky-clean family entertainments as Dick Tracy and the rerelease of The Jungle Book — could become one of the biggest hits of the year.

Now that I’ve seen it, I still think Pretty Woman celebrates prostitution while trashing real-life prostitutes, but not in the way that I originally imagined, and not in a way that is readily apparent. In fact the film manages to espouse prostitution while cleverly concealing the fact that it is doing so. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (February 1, 1989). — J.R.

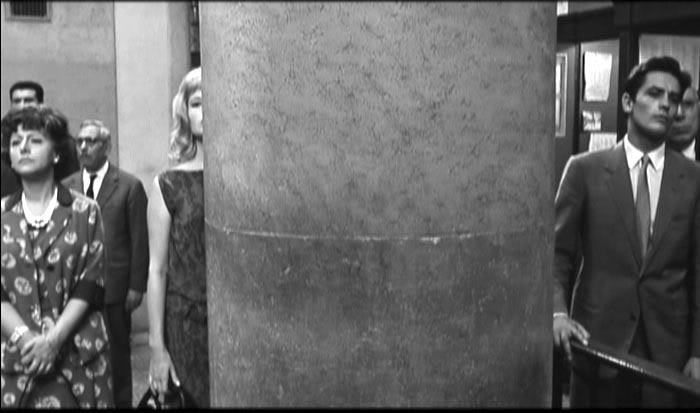

The conclusion of Michelangelo Antonioni’s loose trilogy (preceded by L’Avventura and La Notte), this 1961 film is conceivably the best in Antonioni’s career, but significantly it has the least consequential plot. A sometime translator (Monica Vitti) recovering from an unhappy love affair briefly links up with a stockbroker (Alain Delon) in Rome, though the stunning final montage sequence — perhaps the most powerful thing Antonioni has ever done — does without these characters entirely. Alternately an essay and a prose poem about the contemporary world in which the love story figures as one of many motifs, this is remarkable both for its visual/atmospheric richness and its polyphonic and polyrhythmic mise en scene (Antonioni’s handling of crowds at the Roman stock exchange is never less than amazing). In Italian with subtitles. 123 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From The Soho News (July 8, 1981). From today’s vantage point (fall 2016), I think I was much too needlessly unkind here to Blake Edwards, not to mention Paul Schrader. But I would add that part of my charge against S.O.B. would apply equally well to The Player: the alleged hatchet-job is really a celebration, and one that depends on the hypocritical complicity of the viewer. -– J.R.

Disney Animation and Animators

Whitney Museum of American Art.

through September 6

S.O.B.

Written and directed by Blake Edwards

Postmodernism is a jive-ass, commercially-minded, art-related movement which seems to be guided by three central tenets or market strategies” (1) if it works, it’s art; (2) if it fails, it’s politics; (3) if it sells, it works. It also betrays an overall yearning aspiration to reconcile radically opposed positions, like Karl Marx and Ayn Rand. (If you had to boil it down to a single tenet, perhaps this would be Total Gross Precedes Essence, with Existence left out of the formula.)

The spiritual home and stomping ground of postmodernism is Southern California, although a lot of its promotional rhetoric seems to get pumped through New York channels. Its principal aim often appears to be to destroy the individual and combined existential integrity of both art and politics by turning them into the two faces of commerce, this making them “available” (at a price) to everyone. Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, May 1976 (Vol. 43, No. 508). Many years later, I revised and expanded this review for an essay commissioned by the Masters of Cinema DVD of Spione, called “Inside the Vault”. –- J.R.

Spione (The Spy)

Germany, 1928Director: Fritz Lang

An unidentified European country. After two treaties are stolen by a spy ring, and all the best agents of Burton Jason, head of the Sectet Service, have been killed while attempting to recover them, Jason summons detective Donald Tremaine, who arrives disguised as a tramp. The master-mind of the thefts, Haghi — an apparent cripple who runs a bank and has built a spy ring mainly out of criminals he has secretly sprung from prison — assigns Sonia to find out from Tremaine when a new treaty is to be signed. Rushing into Tremaine’s hotel suite after shooting a man whom she claims attacked her (and who survives thanks to a wallet in his breast pocket which stops the bullet), she gets Tremaine to hide her and quickly charms him. Charmed herself, she begs Haghi to take her off the case, but he forces her to write Tremaine a letter, which he dictates. Tremaine comes to her house and they make a date for dinner, but she is called away from the restaurant by Haghi. Read more

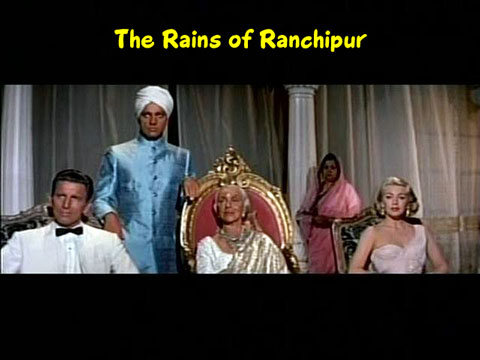

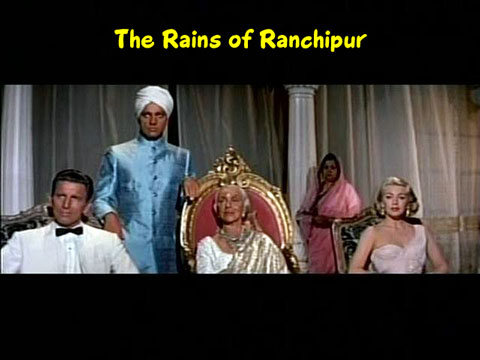

Fresh from one of the my favorite boutique labels, Twilight Time, comes the Blu-Ray of Jean Negulesco’s opulent, ridiculously overripe 1955 CinemaScope remake of his own 1939 The Rains Came, which I hadn’t seen since I was 13 or so — a highly enjoyable bad movie, which on some level must mean that it also qualifies as a good movie. Perhaps the most morally neutral adjective to be employed here is one of those used by Julie Kirgo, Twilight Time’s ever-industrious in-house scribe: “lurid”.

None of the characters here is ever quite believable — Lana Turner as wealthy, aristocratic maneater Lady Esketh, Michael Rennie as her self-hating cuckold husband, Richard Burton as the innocent and idealist doctor and one-time Untouchable who falls heavily for Lady Esketh, quotes Eliot and Shakespeare, and spouts profound aphorisms, Eugenie Leontovich as the urbane Maharani who raised the doctor, Fred MacMurray as a well-to-do and secretly virtuous alcoholic, Joan Caulfield as the latter’s oversheltered protégé — but every one of them is, shall we say, exceptionally vivid, and the performances are all much better than they need to be. Similarly, the special effects trotted out for the title catastrophe are worthy of Cecil B. De Mille, with Lahore, Pakistan and (I presume) various Fox soundstages standing in for Ranchipur as fearlessly as the mesmerizing White Russian refugee Leontovich pretends to be Indian, or the no less self-validating Lana Turner pretends to be candid. Read more

This review appeared originally in Cineaste, Fall 2001. — J.R.

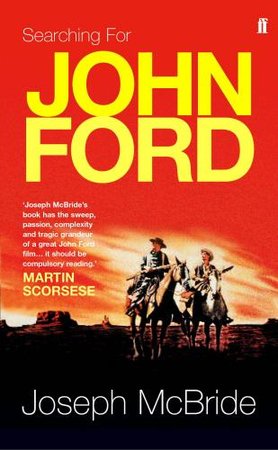

Searching for John Ford

by Joseph McBride. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2001. 838 pp., illus, Hardcover: $40.00

Only sixty pages longer than his other lengthy biography, Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success (1992), Joseph McBride’s Searching For John Ford is, in fact, a very different sort of book, and not only because the size and importance of Ford’s work is considerably greater. The earlier volume — a devastating act of demystification that sought to dismantle not only a populist hero, but also the national mythology that virtually willed him into existence — made the value of Capra’s films appear almost secondary. It was suggested, moreover, by Gilberto Perez that McBride even seemed to gloat over the failure of Capra’s farm — that the author’s apparent animus toward his subject spilled over into his cultural critique. For me, the self-deluding aspects of Capracorn — in contradistinction to the erotic splendors of Capra’s best Thirties work — made such a relentless assault on the mythology both useful and necessary.

One might argue that Ford’s career, by contrast, is much too varied and complex to suit any such monolithic agenda, moral or otherwise. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 20, 1990). — J.R.

JESUS OF MONTREAL

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Denys Arcand

With Lothaire Bluteau, Catherine Wilkening, Johanne-Marie Tremblay, Remy Girard, Robert Lepage, Gilles Pelletier, Yves Jacques, and Arcand.

It must have been about 30 years ago that I saw Jules Dassin’s He Who Must Die, a popular art-house movie at the time and one of my first foreign films. Dassin, an American expatriate chased to Europe by the Hollywood blacklist, was a highly skilled film noir director whose best efforts included The Naked City, Thieves’ Highway, and Night and the City. He Who Must Die, set on Crete in 1921, was a French picture based on Nikos Kazantzakis’s novel The Greek Passion, concerning the performers in a passion play whose theatrical roles take over their real lives as they suffer from Turkish oppression; the theme was that if Christ came back today, he would be crucified all over again.

I was a teenager at the time, and being none too versed in what was considered sophisticated in film in 1959, I was moved to tears. This was at a time when the French New Wave had barely made a ripple in the American consciousness, and shortly before Dassin’s film was ridiculed by critics I admired, like Pauline Kael and Dwight Macdonald, as the acme of arty pretension. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 1, 1994). — J.R.

A beautiful and powerful spiritual epic from South Korea (1991), directed by Im Kwon-taek — Korea’s most famous and popular film director, whose filmography runs to 80-odd titles — from an ambitious script by Kim Yong-ok. Covering roughly four decades from the 1860s through the 1890s, the film charts the growth and eventual stamping out of Kae Byok (from which comes the film’s original Korean title), a radically humanist and egalitarian religious sect founded on the belief that God is everyone and everything; in particular it focuses on the sect’s charismatic leader, Hae-Wol (very effectively played by Lee Duk-hwa), who was born a poor farmer, and his three wives. Though closer in some ways to a historical pageant than a conventional narrative, with numerous printed titles inserted at the beginning of various episodes to explain their historical contexts, the film is anything but slow or ponderous (unlike Wyatt Earp, for instance). Composed mainly of short, economical scenes, flurries of action against breathtaking landscapes that stunningly reflect the seasons, this may make more intoxicating use of color than any Asian film I’ve seen since Mizoguchi’s New Tales of the Taira Clan, and the story itself has an epic grandeur worthy of Mizoguchi. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 15, 1994). — J.R.

The second installment (1992) in Eric Rohmer’s “Tales of the Four Seasons” centers on a young Parisian woman, aptly called Felicie, who fluctuates between two suitors — a pensive local librarian and the owner of a chain of beauty salons who’s moving to Nevers and wants her and her young daughter to come live with him. But in the back of her mind she’s holding out for the return of a former lover, the father of her daughter, whom she lost track of after they spent a summer holiday together; she accidentally gave him the wrong address when he moved away and she never heard from him again. The conception may be a little too rigorously Catholic for some tastes (including mine), but Rohmer has become such a master of his chosen classic genre — the crystalline philosophical tale of character and romantic choice — that this is a nearly perfect work, in performance as well as execution, with an apposite if ambiguous extended reference to Shakespeare’s A Winter’s Tale in the penultimate act. With Charlotte Very, Frederic Van Dren Driessche, Michel Voletti, and Herve Furic. Music Box, Friday through Thursday, July 15 through 21. Read more

A chapter from Film: The Front Line 1983.

All the major recent films of Robert Breer, an American who spent a crucial decade in Paris (1959-1969), are available in this country. But considering the fact that they’re independent animation, and that Breer is a one-man industry and not a Hollywood studio, they might as well be on the moon. They clearly inhabit a ghetto even more confining than that of the “foreign film,” because most critics lack an apparatus for dealing with them; hence, they find it easier to pretend that these works don’t exist. As uncontroversial as it might appear to be in most contexts, it is probably not irrelevant to note that when one of Breer’s most recent films, the characteristically brilliant Swiss Army Knife with Rats and Pigeons (1980) was screened at a New York Film Festival press show in 1982, it was rudely and audibly (if inexplicably) hissed. And candor compels me to admit that although — perhaps even because — Robert Breer impresses me as the key figure in avant-garde animation, my task in this book would be a good deal simpler if I too could pretend that he doesn’t exist, for the challenge of his work is precisely its capacity to reveal the inadequacy of any criticism that attempts to describe it — the challenge that can often keep the very best new avant-garde work either ignored (the standard journalistic ploy) or dealt with only circumspectly (the standard academic ploy). Read more

From the Chicago Reader (November 15, 2007). — J.R.

Still Lives: The Films of Pedro Costa Gene Siskel Film Center, 11/17—12/4

The cinema of Portuguese filmmaker Pedro Costa is populated not so much by characters in the literary sense as by raw essences — souls, if you will. This is a trait he shares with other masters of portraiture, including Robert Bresson, Charlie Chaplin, Jacques Demy, Alexander Dovzhenko, Carl Dreyer, Kenji Mizoguchi, Yasujiro Ozu, and Jacques Tourneur. It’s not a religious predilection but rather a humanist, spiritual, and aesthetic tendency. What carries these mysterious souls, and us along with them, isn’t stories — though untold or partially told stories pervade all six of Costa’s features. It’s fully realized moments, secular epiphanies.

Born in Lisbon in 1959, by his own account Costa grew up without much of a family, and famly life — actual or simulated — is central to his work. All his films are about the dispossessed in one way or another. As the Argentine film critic Quintín puts it, he’s “a cool guy — very rock ’n’ roll” (in fact he was a rock guitarist before he turned to filmmaking). “At the same time,” Quintín continues, he is “quietly telling whoever will listen that cinema is exactly the opposite of what 99% of the film world thinks, and he is getting more radical every day.” Read more