My response to a survey in Framework (Volume 50, No. 1 & 2, Spring & Fall 2009). I’ve retained only the first part — the question part — of Jonathan Buchsbaum and Elena Gorfinkel’s Introduction to the survey:

This dossier on cinephilia gathers responses to the following question:

“What is being fought for by today’s cinephilia(s)?

At the end of La Cinéphilie (2003), Antoine de Baecque wrote that classical cinephilia died in 1968, following the failure of cinema to film the political events of that year. Since that time, still according to de Baecque, the terrain of cinephilia changed radically as television and publicity/ advertising ‘invaded the domain of images.’ The proliferation of images has only accelerated with technological change ever since, hurtling through the internet and telecommunications.

Whatever the current status of cinephilia, certainly there are new cinephiles, even if they no longer hone their passion primarily in film theaters. But what is being fought for in this new generation of cinephilia? What causes animate cinephilia today and how are these new modes different from the ‘classical cinephilia’?

If, in particular, the Cahiers du Cinéma critics won their battles for auteurism, now part of most critics’ lingua franca, are there new critical paradigms of emergent polemics to complement, replace, or contest the earlier cinephilia? Read more

This is the 13th one-page column I published in Cahiers du Cinéma España; it ran in their July-August 2009 issue. — J.R.

Writing from Chicago in May, during the Cannes film festival, I’ve been reflecting lately how much this festival remains a spectator sport even for those who don’t attend it. I’ve attended it nine times in all, 1970-1973 and 1994-1998, and my most enduring impression about it is how quickly everything that happens there gets turned into some form of business — a process that is both hilarious and somewhat horrifying.

Two immediate examples come to mind which occurred during my first and most recent visits there. In 1970, I attended the world premiere of Woodstock, only five days after four students were shot and killed by National Guardsmen at Kent State University in Ohio. Michael Wadleigh, the hippie director — a tall, commanding figure dressed in suede — dedicated the film to those four students and to “the many deaths to come” in the ongoing political struggles of the period. When the screening was over, he stood by the exit and calmly handed out black arm bands to anyone who wanted to wear one. I wore one myself for a day or two. Read more

Chicago Reader, 2005:

The World (Jia Zhang-ke)

Not on the Lips (Alain Resnais)

A History of Violence (David Cronenberg)

Ten Skies (James Benning)

Tropical Malady (Apichatpong Weerasethakul)

Howl’s Moving Castle (Hayao Miyazaki) & Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (Tim Burton)

Yes (Sally Potter) & Capote (Bennett Miller)

Michelangelo Eye to Eye (Michelangelo Antonioni) & Saraband (Ingmar Bergman)

Broken Flowers (Jim Jarmusch) & Me and You and Everyone We Know (Miranda July)

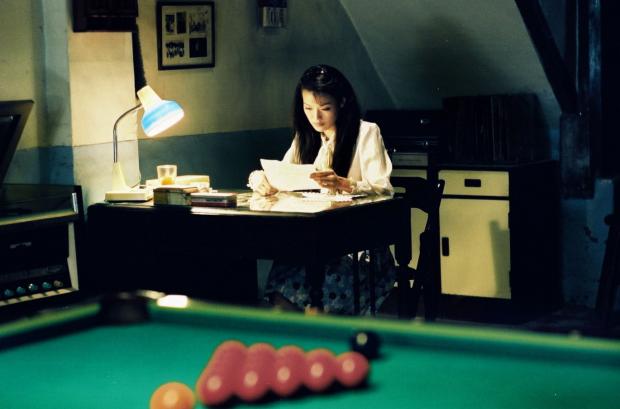

The Girl from Monday (Hal Hartley) & 2046 (Wong Kar-wai)

Chicago Reader, 2006:

Cafe Lumiere (Hou Hsiao-hsien) & Three Times (Hou Hsiao-hsien)

Army of Shadows (1969, Jean-Pierre Melville) & Statues Also Die (1953, Resnais/Marker/Cloquet)

The War Tapes (Deborah Scranton) & Iraq in Fragments (James Longley)

Cuadecuc-Vampir (1970, Pere Portabelle) & Warsaw Bridge (1990, Portabella)

Find Me Guilty (Sidney Lumet) & Half Nelson (Ryan Fleck)

Citadel (Atom Egoyan) & The Power of Nightmares (Adam Curtis)

The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada (Tommy Lee Jones) & The Illusionist (Neil Burger)

Ask the Dust (Robert Towne) & Hollywoodland (Allen Coulter)

Moments Choisis des Histoire(s) du Cinéma (Godard) & My Dad Is 100 Years Old (Maddin)

Fast Food Nation (Richard Linklater) & Bobby (Emilio Estevez)

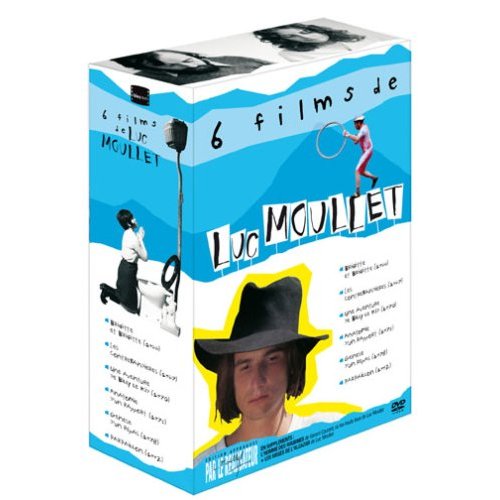

DVD Beaver, 2006:

1. 6 Films de Luc Moullet (Luc Moullet, 2006), Blaq Out; multizone NTSC

2. Read more

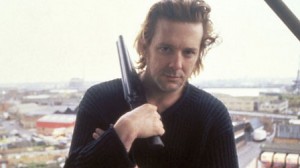

Mickey Rourke is an IRA terrorist tired of killing and looking for a way out of the United Kingdom; Alan Bates is a London mobster doubling as a mortician who offers him an escape route if he bumps off another crook; Bob Hoskins is a priest who witnesses the latter murder. It’s theoretically possible that there was once something more to this than the disjointed thriller now on view: director Mike Hodges and Rourke have both disowned producer Peter Snell’s extensive reediting of Hodges’s cut, which apparently strips down the atmospherics for action, and Bates and Hoskins have gone on record as preferring the original version as well. In the film as it stands, Bates is ghoulishly good, Rourke impossibly angelic, and Hoskins seemingly bemused by his part; neither intimations of The Informer and Odd Man Out nor Bill Conti’s wallpaper score can redeem the awkward cross-purposes. With a screenplay by Edmond Ward and Martin Lynch. (JR) Read more

From Sight and Sound (Spring 1990). — J.R.

Despite worries that the passionate eclecticism of the late Hubert Bals in steering the Rotterdam Festival would be a hard act to follow, Marco Müller, in his first year as director, maintained the festival’s maverick spirit and cozy intensity while adding his own personal stamp. Increasing the usual number of films by 50 per cent may have taxed his staff, but publishing excellent bilingual monographs (on Ritwik Ghatak, David Cronenberg and Gennadi Sjpalikov) gave the audience a good head start.

Best of all, Müller continued the Rotterdam tradition of offering a slew of uncommon pleasures unavailable elsewhere. Where else could one find André Labarthe’s TV interview-portraits of directors, the multiple versions of Straub and Huillet’s The Death of Empedocles and Black Sin (as well as the premiere of their intriguing 51-minute Cézanne), Nanni Moretti’s daffy and lively Palombella Rosa, and perhaps the best films to date of Eduardo de Gregorio, Wayne Wang and Otar Iosseliani?

The work by American independents was especially strong and varied. Leslie Thornton’s freakishly disturbing and still-in-progress Peggy and Fred in Hell, split between film and video, plants two odd children in an apocalyptic black and white universe of found objects, found footage and lost meanings, perpetually reinventing culture as it slips from their (and our) grasp. Read more

From the February 24, 2006 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Late Chrysanthemums

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Mikio Naruse

Written by Sumie Tanaka and Toshiro Ide

With Haruko Sugimura, Sadako Sawamura, Chikako Hosokawa, Yuko Mochizuki, Ken Uehara, Hiroshi Koizumi, and Ineko Arima

Depressing movies with unhappy endings are often seen as offering a bracing contrast to the standard Hollywood fare. This may help explain the appeal of Brokeback Mountain, whose drafts of misery are seen by some people as daringly honest and authentic.

I wonder. Some lives are full of misery, but this doesn’t mean movies that reflect them are automatically more truthful. If the shepherds played by Heath Ledger and Jake Gyllenhaal had sustained a happy, loving relationship over several decades in spite of everything, Brokeback Mountain might have been truly daring — and it wouldn’t have been less believable. The impulse to privilege the dark is hardly new; in prerevolutionary Russian cinema, tragic plots ending in suicide were so common and popular that some Hollywood imports with happier endings were revised to make them more “commercial.” I would argue that a certain complacency surrounds some of these doom-ridden scenarios, especially ones that suggest social change is impossible — a vested interest in the status quo, even conservatism, seems to lurk behind the apparent apoliticism. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 26, 2001). — J.R.

The Pledge

***

Directed by Sean Penn

Written by Jerzy Kromolowski and Mary Olson-Kromolowski

With Jack Nicholson, Patricia Clarkson, Benicio Del Toro, Dale Dickey, Aaron Eckhart, Helen Mirren, Tom Noonan, Robin Wright Penn, Vanessa Redgrave, Mickey Rourke, and Sam Shepard.

Blooper Bunny

***

Directed by Greg Ford and Terry Lennon

Written by Ronnie Scheib, Ford, and Lennon

With Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Elmer Fudd, and Yosemite Sam.

The Wedding Planner

**

Directed by Adam Shankman

Written by Pamela Falk and Michael Ellis

With Jennifer Lopez, Matthew McConaughey, Bridgette Wilson- Sampras, Justin Chambers, and Judy Greer.

Shadow of the Vampire

*

Directed by E. Elias Merhige

Written by Steven Katz

With Willem Dafoe, John Malkovich, Catherine McCormack, Eddie Izzard, Cary Elwes, and Udo Kier.

I can’t say that The Pledge, The Wedding Planner, Blooper Bunny, and Shadow of the Vampire have much in common, apart from the fact that they’re showing in Chicago this week. Yet all four do, to different degrees, feed off other movies. Frankly, that’s what I like most about The Wedding Planner — a romantic comedy starring Jennifer Lopez and Matthew McConaughey that aspires to and achieves the goofiness of a studio musical of the early 50s. Read more

From Video Times (February 1986). — J.R.

AGUIRRE, WRATH OF GOD

(1972), C, Director: Werner Herzog. With Klaus Kinski, Roy Guerra, Del Negro, and Helena Rojo. 90 min. Subtitled. Continentai, $39.95. ****

Among contemporary movies that aspire to create the resonance of myth, there are few more compelling than this 1972 masterpiece. Directed by German filmmaker Werner Herzog, the film stars Klaus Kinski in the title role. At once a 16th century Peruvian adventure story about the legend of El Dorado and a somewhat indirect parable about modern imperialism, Aguirre, Wrath of God can be regarded as one of the key influences on Francis Coppola’s 1979 Apocalypse Now. The fact that Herzog himself launched a treacherous journey through the backwaters of Peru in order to film his tale helped to popularize the notion of the director as mad Faustian conquistador. When Herzog himself attempted to surpass Aguirre a decade later with Fitzcarraldo, another insane, “historic” journey up the Amazon, the result was only a pale dilution of the original.

The film opens with a printed title that perfectly establishes the aura of legend: “After the conquest and sack of the Incan empire by Spain, the Indians invented the legend of El Dorado, a land of gold, located in the swamps of the Amazon tributaries. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (November 27, 1992). I couldn’t (and wouldn’t) argue that this treat is necessarily Coppola’s best movie, for reasons given below, but I wonder if it might actually be his most pleasurable, at least on a moment-by-moment (and shot-by-shot) basis. The Blu-Ray only adds to and enhances the richness. — J.R.

BRAM STOKER’S DRACULA

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Francis Ford Coppola

Written by James V. Hart

With Gary Oldman, Winona Ryder, Sadie Frost, Tom Waits, Anthony Hopkins, Keanu Reeves, Richard E. Grant, Cary Elwes, and Bill Campbell.

Geographical spread accounts for some of the major differences between the film culture in this country and the various film cultures in Europe. While overseas the principal film-production centers and intellectual centers are usually located in the same cities — Paris, Rome, London, Madrid, Lisbon, Stockholm, Budapest, Prague — most of the United States stretches between our main film-production center, Hollywood and environs, and our main intellectual center, New York. The practical consequence is that our left hand hasn’t the faintest idea what our right hand is doing.

So much for the geographical split. What might be called the institutional gap is even worse. I’m referring to the profound lack of communication between the film industry (including most movie reviewers) and academic film studies (including intellectuals in adjacent or related fields). Read more

Written for the Dutch magazine de Filmkrant, I believe in early 2004. –J.R.

With Elephant, it’s a pleasure to welcome Gus Van Sant back to the land of the living. His film certainly has its flaws, yet its virtues so outshine them that his past few years in the wilderness can now be forgiven and mainly forgotten.

Gerry at least showed that, after the borderline sellout of Good Will Hunting and the all but unconditional sellout of Finding Forrester, Van Sant was still willing to take sizable risks. It was also interesting to hear him say he was inspired in those risks by such worthy role models as Chantal Akerman, James Benning, Andrei Tarkovsky, Bela Tarr, and Jacques Tati — even if the evidence of their influence wasn’t visible, apart from an overall interest in landscapes and duration.

By contrast, at least two of the major influences on Elephant are plainly visible: Bela Tarr’s Satantango (primary) and Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (secondary). From Satantango comes a complicated overlapping time structure that repeats the same events from a variety of viewpoints, each viewpoint being articulated in mainly extended takes that follow various characters as they walk through many adjacent settings. Read more

From the Winter 1984/1985 Sight and Sound. Only years after writing and publishing this essay, I recalled seeing a test reel of Cinemascope with my father at an Atlanta movie exhibitors convention in 1953, part of which included a refilming of the “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend” number in CinemaScope. I have no idea whether this still exists, but it may help to account for why some people misremember or wrongly identify the entire film as being in CinemaScope.

For those who might be puzzled by the third illustration from the end, this is Dominique Labourier’s character performing in a nightclub in Céline et Julie vont en bateau, in a sequence that precisely parallels the courtroom sequence in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. — J.R.

First Number: “We’re Just Two Little Girls from Little Rock”

I don’t believe in the kino-eye; I believe in the kino-fist. — Sergei Eisenstein

Before even the credit titles can appear, Marilyn Monroe and Jane Russell arrive to a blast of music at screen center from behind a black curtain, in matching orange-red outfits that sizzle the screen — covered with spangles, topped with feathers — to look at one another, toss white ermines toward the camera and out of frame and sing robustly in unison. Read more

My essay for the Criterion DVD (2003). If memory serves, this was probably the first such essay that I wrote for producer Issa Clubb. — J.R.

ORSON WELLES: Fellini is essentially a small-town boy who’s never really come to Rome. He’s still dreaming about it. And we should all be very grateful for those dreams. In a way, he’s still standing outside looking in through the gates. The force of La Dolce Vita comes from its provincial innocence. It’s so totally invented.

PETER BOGDANOVICH: Maybe the “small-town” aspect is why I like I Vitelloni most of all his films.

WELLES: After The White Sheik, it’s the best of all.

Welles’ preference for The White Sheik (1952), Federico Fellini’s first solo feature, over all the others is likely to raise a few eyebrows. Critically speaking, it’s one of the Italian maestro’s most neglected works. In his The Italian Cinema, Pierre Leprohon wrote that it “seems to have been a kind of liquidation of the past in preparation for the emergence of the Fellinian universe, a chance for the author to work off his hatred and rancors.”

Most critics haven’t been so harsh; a more common verdict is to see this as an apprentice work, a sketch of the Fellinian splendors to come. Read more

Commissioned by the French film magazine Positif and published, as two separate but adjacent pieces (critical article and interview), in their 158th issue (avril 1974). I don’t recall it ever appearing before now in English, at least in its entirety. I’ve given it a light edit. The interview was conducted by correspondence, with me in France and McBride in the U.S.

Happily, all three of the McBride films discussed here are available on DVD — David Holzman’s Diary and My Girlfriend’s Wedding paired together in the U.K. (with liner notes by me, available here) and Glen and Randa in the U.S. — J.R.

Due to their limited visibility, the three films of Jim McBride have tended to lead semi-legendary existences. Like seeds scattered to the wind, they’ve cropped up in unexpected places: DAVID HOLZMAN’S DIARY (1967) has been shown at film festivals (it won prizes in Mannheim and Pesaro) and cine-clubs, but not in theaters; MY GIRLFRIEND’S WEDDING (1969), an hour-long film that is not easy to program, turned up on the Second Channel [in France] in a Sunday night “Cine-Club” (autumn 1972), but has rarely been seen elsewhere. GLEN AND RANDA (1971), seen much more widely in the United States — and even making Time magazine’s “Ten Best” list of that year — has been slow in reaching Europe, and surfaced in Pesaro only last September. Read more

From the July 1985 Video Times. — J.R.

An Almost Perfect Affair

(1979), C, Director: Michael Ritchie. With Keith Carradine, Monica Vitti, Raf Vallone, and Dick Anthony Williams. 93 min. PG. Paramount, $59.95. 1 1/2 stars

The seventh and possibly the slightest of Michael Ritchie’s features, An Almost Perfect Affair is a mild romantic comedy that qualifies as pseudosatire — that is, satire that couldn’t conceivably threaten or annoy anyone. Set at the Cannes Film Festival, and largely filmed on location there, the movie chronicles a brief affair between Maria (Monica Vitti) and Hal (Keith Carrdine). Maria is the glamorous wife of a wealthy Italian producer (Raf Vallone), who has a film in the competition. Hal is a callow American independent whose first feature is being shown at the festival. None of this is very believable to anyone who has ever attended the Cannes Festival professionally, but there’s little indication that it’s supposed to be. Much as Manhattan can be viewed in part as valentine to anti-intellectuals who want to feel intellectual, this movie, also made in 1979, is for people who will never go to Cannes but want to feel hip about what happens there.

Inverting the terms that such a comedy would have adopted in the countercultural 1960s, the movie presents the vulgar big-time producer as a man with patriarchal dignity. Read more

From Cineaste, Winter 1996 — J.R.

Even for longtime fans like myself of his independent features — Casual Relations (1973), Mozart in Love (1975), Local Color (1977), The Scenic Route (1978), Imposters (1979), Chain Letters (1984) — Mark Rappaport’s discovery of “fictional autobiography” has led to a quantum leap in his work whose consequences are still being mapped out. After already broaching some of the possibilities of video in his half-hour Postcards (1990) — succeeded most recently by his high-definition super-production Exterior Night (1994) made for German TV — Rappaport virtually invented a new form of film criticism in Rock Hudson’s Home Movies (1992), a melange of clips and commentary built around the premise of a finally out-of-the-closet Hudson (played by actor Eric Farr) reevaluating the subtexts of his films from beyond the grave. A video that won Rappaport more viewers than any of his previous features — especially after he transferred it to film and presented it at festivals — this revisionist take on film history has now been succeeded by From the Journals of Jean Seberg (1995), an even more ambitious and accomplished rereading of our movie past, with Mary Beth Hurt in the title role. After many festival screenings, the new film had its U.S. Read more