This was written in May 2014 for an Italian volume about fantastique cinema between 1980 and 2010 coedited by Antonio Gragnaniello. — J.R.

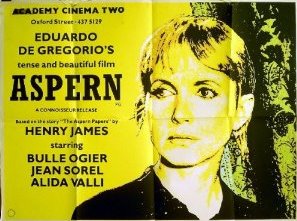

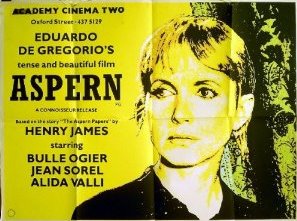

Speaking to Tom Milne and Richard Combs in Monthly Film Bulletin, the director of Aspern, Eduardo de Gregorio (1942-2012), avowed that “it was never meant to be a fantastique film”— which isn’t surprising given that its source, Henry James’ novella The Aspern Papers, has no relation to that genre either. But it was regarded by several French critics as having some relation to fantastique, apparently for two reasons: because fantastique as opposed to fantasy is often regarded as a matter of style and/or atmosphere rather than content, and because the better known works of de Gregorio — such as his scripts for Jacques Rivette’s Céline et Julie vont en bateau, Duelle, and Noroît and his own Sérail and Tangos volés—clearly belong to fantastique, while his work as a whole has clear links to both the 19th century Gothic tradition and the so-called “magical realism” of 20th century Latin American literature.

Even though much of Henry James’ dialogue is carried over into Aspern (translated into French), its basic plot — an obsessive literary scholar (the narrator in James’ tale) insinuates himself into the Venice household of an aged woman cared for by her lonely spinster niece with the aim of procuring her love letters from Aspern, a long-deceased romantic poet she was once involved with — undergoes several decisive changes in de Gregorio’s version, scripted by his partner at the time, Michael Graham. Read more

From The Soho News (November 24, 1981). — J.R.

Nick’s Movies (Nicholas Ray retrospective)

The Public Theater through December 13

Fantasy and counter-fantasy are perpetually at war in the films of Nicholas Ray — accounting in no small measure for the highly charged heat, light, fury, beauty, and pain that most of them project. In its most brilliant representations — the separate divisions of Vienna’s saloon in Johnny Guitar (1954), an almost surrealist Western; the house and mind of Ed Avery in Bigger Than Life (1956), an almost expressionist domestic melodrama — this graphic warfare actually becomes expressed in terms of discrete zones of action and confinement. “Down there I sell whisky and cards,” announces the imperious Vienna (Joan Crawford) on a stairway, gun in hand, to an itchy search party below that’s somewhere between a lynch mob and a sheriff’s posse. “All you can get up these stairs is a bullet in the head.”

Or consider another scene, one of the most memorable jaded love duets in movies, again spelled out through architecture and spatial balances as well as words and faces. Johnny Guitar (Sterling Hayden) sits at a kitchen table, drink in hand, while Vienna stands behind him, on the other side of a serving window, also facing us. Read more

Children of Men ***

Directed by Alfonso Cuaron

Written by Cuaron, Timothy J. Sexton, David Arata, Mark Fergus, and Hawk Ostby with Clive Owen, Julianne Moore, Claire-Hope Ashitey, Michael Caine, Pam Ferris, and Chiwetel Ejiofor

Pan’s Labyrinth ****

Directed and written by Guillermo del Toro

With Sergi Lopez, Maribel Verdu, Ivana Baquero, Ariadna Gil, and Doug Jones

Over the past few years three highly talented and ambitious young Mexican film directors — Alfonso Cuaron, Guillermo del Toro, and Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu — have made their way into the American mainstream. All three seem to have managed this trick by defining themselves mainly in terms of genre, which isn’t surprising given the industry’s insistence that everything be defined according to pitches and formulas, all in 25 words or less — the consequence of a desire to exhaust existing markets rather than attempt to nurture or create new ones.

Cuaron’s done some children’s fantasy (A Little Princess, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban) and literary adaptation (Great Expectations), a sex comedy/road movie/coming-of-age story (Y Tu Mama Tambien), and now an action-adventure/SF/war movie (Children of Men). His most ambitious movies seem to cram together several genres — or at least the suits’ notions of genres. Read more