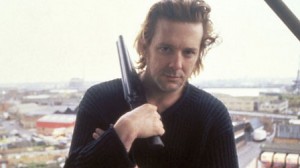

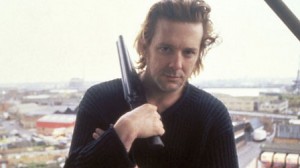

Mickey Rourke is an IRA terrorist tired of killing and looking for a way out of the United Kingdom; Alan Bates is a London mobster doubling as a mortician who offers him an escape route if he bumps off another crook; Bob Hoskins is a priest who witnesses the latter murder. It’s theoretically possible that there was once something more to this than the disjointed thriller now on view: director Mike Hodges and Rourke have both disowned producer Peter Snell’s extensive reediting of Hodges’s cut, which apparently strips down the atmospherics for action, and Bates and Hoskins have gone on record as preferring the original version as well. In the film as it stands, Bates is ghoulishly good, Rourke impossibly angelic, and Hoskins seemingly bemused by his part; neither intimations of The Informer and Odd Man Out nor Bill Conti’s wallpaper score can redeem the awkward cross-purposes. With a screenplay by Edmond Ward and Martin Lynch. (JR) Read more

From Sight and Sound (Spring 1990). — J.R.

Despite worries that the passionate eclecticism of the late Hubert Bals in steering the Rotterdam Festival would be a hard act to follow, Marco Müller, in his first year as director, maintained the festival’s maverick spirit and cozy intensity while adding his own personal stamp. Increasing the usual number of films by 50 per cent may have taxed his staff, but publishing excellent bilingual monographs (on Ritwik Ghatak, David Cronenberg and Gennadi Sjpalikov) gave the audience a good head start.

Best of all, Müller continued the Rotterdam tradition of offering a slew of uncommon pleasures unavailable elsewhere. Where else could one find André Labarthe’s TV interview-portraits of directors, the multiple versions of Straub and Huillet’s The Death of Empedocles and Black Sin (as well as the premiere of their intriguing 51-minute Cézanne), Nanni Moretti’s daffy and lively Palombella Rosa, and perhaps the best films to date of Eduardo de Gregorio, Wayne Wang and Otar Iosseliani?

The work by American independents was especially strong and varied. Leslie Thornton’s freakishly disturbing and still-in-progress Peggy and Fred in Hell, split between film and video, plants two odd children in an apocalyptic black and white universe of found objects, found footage and lost meanings, perpetually reinventing culture as it slips from their (and our) grasp. Read more

From the February 24, 2006 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Late Chrysanthemums

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Mikio Naruse

Written by Sumie Tanaka and Toshiro Ide

With Haruko Sugimura, Sadako Sawamura, Chikako Hosokawa, Yuko Mochizuki, Ken Uehara, Hiroshi Koizumi, and Ineko Arima

Depressing movies with unhappy endings are often seen as offering a bracing contrast to the standard Hollywood fare. This may help explain the appeal of Brokeback Mountain, whose drafts of misery are seen by some people as daringly honest and authentic.

I wonder. Some lives are full of misery, but this doesn’t mean movies that reflect them are automatically more truthful. If the shepherds played by Heath Ledger and Jake Gyllenhaal had sustained a happy, loving relationship over several decades in spite of everything, Brokeback Mountain might have been truly daring — and it wouldn’t have been less believable. The impulse to privilege the dark is hardly new; in prerevolutionary Russian cinema, tragic plots ending in suicide were so common and popular that some Hollywood imports with happier endings were revised to make them more “commercial.” I would argue that a certain complacency surrounds some of these doom-ridden scenarios, especially ones that suggest social change is impossible — a vested interest in the status quo, even conservatism, seems to lurk behind the apparent apoliticism. Read more