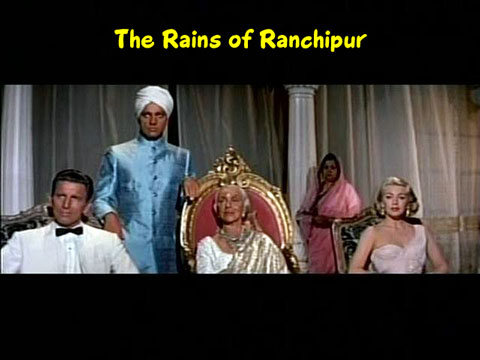

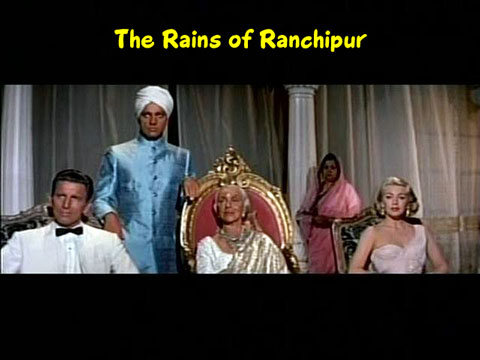

Fresh from one of the my favorite boutique labels, Twilight Time, comes the Blu-Ray of Jean Negulesco’s opulent, ridiculously overripe 1955 CinemaScope remake of his own 1939 The Rains Came, which I hadn’t seen since I was 13 or so — a highly enjoyable bad movie, which on some level must mean that it also qualifies as a good movie. Perhaps the most morally neutral adjective to be employed here is one of those used by Julie Kirgo, Twilight Time’s ever-industrious in-house scribe: “lurid”.

None of the characters here is ever quite believable — Lana Turner as wealthy, aristocratic maneater Lady Esketh, Michael Rennie as her self-hating cuckold husband, Richard Burton as the innocent and idealist doctor and one-time Untouchable who falls heavily for Lady Esketh, quotes Eliot and Shakespeare, and spouts profound aphorisms, Eugenie Leontovich as the urbane Maharani who raised the doctor, Fred MacMurray as a well-to-do and secretly virtuous alcoholic, Joan Caulfield as the latter’s oversheltered protégé — but every one of them is, shall we say, exceptionally vivid, and the performances are all much better than they need to be. Similarly, the special effects trotted out for the title catastrophe are worthy of Cecil B. De Mille, with Lahore, Pakistan and (I presume) various Fox soundstages standing in for Ranchipur as fearlessly as the mesmerizing White Russian refugee Leontovich pretends to be Indian, or the no less self-validating Lana Turner pretends to be candid. Read more

This review appeared originally in Cineaste, Fall 2001. — J.R.

Searching for John Ford

by Joseph McBride. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2001. 838 pp., illus, Hardcover: $40.00

Only sixty pages longer than his other lengthy biography, Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success (1992), Joseph McBride’s Searching For John Ford is, in fact, a very different sort of book, and not only because the size and importance of Ford’s work is considerably greater. The earlier volume — a devastating act of demystification that sought to dismantle not only a populist hero, but also the national mythology that virtually willed him into existence — made the value of Capra’s films appear almost secondary. It was suggested, moreover, by Gilberto Perez that McBride even seemed to gloat over the failure of Capra’s farm — that the author’s apparent animus toward his subject spilled over into his cultural critique. For me, the self-deluding aspects of Capracorn — in contradistinction to the erotic splendors of Capra’s best Thirties work — made such a relentless assault on the mythology both useful and necessary.

One might argue that Ford’s career, by contrast, is much too varied and complex to suit any such monolithic agenda, moral or otherwise. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 20, 1990). — J.R.

JESUS OF MONTREAL

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Denys Arcand

With Lothaire Bluteau, Catherine Wilkening, Johanne-Marie Tremblay, Remy Girard, Robert Lepage, Gilles Pelletier, Yves Jacques, and Arcand.

It must have been about 30 years ago that I saw Jules Dassin’s He Who Must Die, a popular art-house movie at the time and one of my first foreign films. Dassin, an American expatriate chased to Europe by the Hollywood blacklist, was a highly skilled film noir director whose best efforts included The Naked City, Thieves’ Highway, and Night and the City. He Who Must Die, set on Crete in 1921, was a French picture based on Nikos Kazantzakis’s novel The Greek Passion, concerning the performers in a passion play whose theatrical roles take over their real lives as they suffer from Turkish oppression; the theme was that if Christ came back today, he would be crucified all over again.

I was a teenager at the time, and being none too versed in what was considered sophisticated in film in 1959, I was moved to tears. This was at a time when the French New Wave had barely made a ripple in the American consciousness, and shortly before Dassin’s film was ridiculed by critics I admired, like Pauline Kael and Dwight Macdonald, as the acme of arty pretension. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 1, 1994). — J.R.

A beautiful and powerful spiritual epic from South Korea (1991), directed by Im Kwon-taek — Korea’s most famous and popular film director, whose filmography runs to 80-odd titles — from an ambitious script by Kim Yong-ok. Covering roughly four decades from the 1860s through the 1890s, the film charts the growth and eventual stamping out of Kae Byok (from which comes the film’s original Korean title), a radically humanist and egalitarian religious sect founded on the belief that God is everyone and everything; in particular it focuses on the sect’s charismatic leader, Hae-Wol (very effectively played by Lee Duk-hwa), who was born a poor farmer, and his three wives. Though closer in some ways to a historical pageant than a conventional narrative, with numerous printed titles inserted at the beginning of various episodes to explain their historical contexts, the film is anything but slow or ponderous (unlike Wyatt Earp, for instance). Composed mainly of short, economical scenes, flurries of action against breathtaking landscapes that stunningly reflect the seasons, this may make more intoxicating use of color than any Asian film I’ve seen since Mizoguchi’s New Tales of the Taira Clan, and the story itself has an epic grandeur worthy of Mizoguchi. Read more