From the Chicago Reader (May 19, 2000). — J.R.

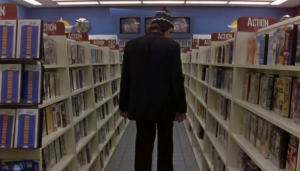

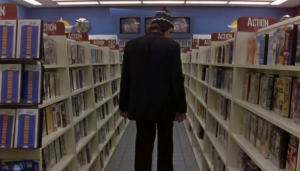

It’s fitting that the most existential of plays should function as a kind of test, and fortunate that the first Michael Almereyda picture to get full mainstream exposure should also turn out to be his best to date. But what’s being tested isn’t either Shakespeare or Almereyda but the present moment: that is, the film asks how and how much we’re capable of living in the world Shakespeare wrote about. Wittily and tragically updating the play’s action to corporate America in general and New York in particular, Almereyda is no Orson Welles, but he begins to seem like one when he’s castigated for not doing his Shakespeare like Kenneth Branagh; the censure recalls all the times square and professional Laurence Olivier was used as a reproach to Welles’s hip “amateurism.” This is gloriously amateurish, the way all of Almereyda’s best movies are, so it’s rewarding to see how Julia Stiles’s Ophelia harks back to Suzy Amis in Almereyda’s Twister, how some of the intimate interiors recall Another Girl Another Planet (his second-best movie), and how the use of video as a kind of Greek chorus to the action, an Almereyda specialty, bears special fruit in a postmodernist climate where “To be or not to be” is recited in the action section of a Blockbuster and Hamlet (Ethan Hawke, better than you’d expect) lards his video production of The Mousetrap with all sorts of found footage. Read more

Two new British Film Institute digital releases related to Orson Welles, both due out later this month, arrived in my mailbox yesterday, the day after I submitted my Fall DVD column to Cinema Scope —Around the World with Orson Welles (1955) on Blu-Ray and Chuck Workman’s 2014 Magician: The Astonishing Life and Work of Orson Welles on DVD. In their very different ways, both are worthy items that are well worth having, which is largely why I’m posting something about them here.

Around the World with Orson Welles is a shamefully neglected TV series directed by Welles of six half-hour episodes, made around the same time as Mr. Arkadin (for the same French producer, Louis Dolivet), with a remarkable range of topics including Basque culture (two episodes), Vienna coffee houses and pastry, the bohemian avant-garde in Paris (including a reading of Lettrist poetry: see still below), London pensioners, and the Spanish bullfight (with Mr. and Mrs. Kenneth Tynan as cohosts); a seventh episode — the first to be shot, but never completed — was an investigative crime report set in the French provinces, The Dominici Affair, and an English version of Christophe Cognet’s 52-minute, 2000 French documentary about this project is one of the two extras included. Read more

Film history that is open to the present

Last month Alexander Horwath, director of the Austrian Film Museum, sent me a press release about an ambitious and audacious retrospective he’s presenting throughout November entitled “Notre Musique,” devoted to “forty major works of fictional and documentary cinema made between 2000 and 2006.” “Film museums are often — and justifiably — viewed as places where an awareness of the historic foundations of contemporary cinema can evolve,” he begins. “Yet a reverse perspective is equally important — an approach to film history that is open to the present.” His selection, he adds, “is not so much influenced by the best-known or `most-discussed’ films of recent years but rather by the unbroken capacity of cinema to bear witness to life on this planet [his emphasis] — not just in the sense of documentation but also as an illumination of circumstances that habor a potential for change.” What he’s put together, in short, is a group of films that are supposed to bear witness, politically and responsibly, to the present moment — a daring gesture if one considers Jacques Rivette’s plausible statement in a Cahiers du Cinéma roundtable over 40 years ago, that it’s virtually impossible for a critic to know the long-term value of a film when it first appears.

Read more