From Projections 8, edited by John Boorman and Walter Donohue, 1998. Subtitled Film-makers on Film-makers, this issue of the periodic Faber and Faber publication was devoted specifically to what it called ‘criticism,’ spurred jointly by a brief declaration by Bruce Willis at Cannes in 1997 (‘Nobody up here pays attention to reviews…most of the written word has gone the way of the dinosaur’) and a lengthy essay by François Truffaut, ‘What Do Critics Dream About?’, introducing his 1974 collection The Films of My Life. As nearly as I can remember, I was one of the nine critics (along with Gilbert Adair, Geoff Andrew, Michel Ciment, Peter Cowie, Kenneth Turan, Alexander Walker, Armond White, and Jonathan Romney) asked to respond to these two declarations of principles. (I haven’t been able to find Truffaut’s essay online, but an excerpt from it can be found here: https://www.lostinthemovies.com/2009/04/what-do-critics-dream-about.html.)

If my comments about the Truffaut essay sound harsh, I hasten to add that I still regard his early criticism as seminal — perhaps even the most seminal that was written by Bazin’s younger disciples, as Godard, among others, has suggested. -– J.R.

I welcome the prospect of an issue of Projections devoted to `the art and practice of film criticism’, though given the present climate that circulates around film discourse in general — a climate at once pre-critical and post-critical in which the static produced by commerce tends to drown out most of the murmurs associated with criticism — I’m more than a little fearful about what results such an inquiry is likely to yield. Read more

Written for Sight and Sound (March 2017). — J.R.

WE’LL ALWAYS HAVE CASABLANCA

The Life, Legend, and Afterlife of Hollywood’s Most Beloved Movie

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

By Noah Isenberg. W.W. Norton & Co., 334 pp. US$27.95. ISBN 9780393243123.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

Reviewed by Jonathan Rosenbaum

I’ve never been asked to select my favourite ‘guilty pleasures’ in movies, but I suspect that if I were, Gone With the Wind and Casablanca — two highly accomplished and engrossing pieces of dubious Hollywood hokum — could easily head the list. Yet it’s one of the signal virtues of Noah Isenberg’s We’ll Always Have Casablanca to suggest that the true sources of Casablanca’s popularity place it well beyond the racial and racist subtexts of Gone With the Wind.

In the case of the latter film, we have the benefit of Molly Haskell’s Frankly, My Dear (2009), a superb critical and ideological unpacking of both the Margaret Mitchell novel and the David O. Selznick blockbuster. Isenberg, an academic and a scholar more than a critic — director of screen studies and professor of culture and media at New York’s New School, and best known among cinephiles as an Edgar G. Ulmer specialist — hasn’t given us the same sort of book as Haskell, although he’s produced a volume that’s equally accessible and nearly as valuable in explaining the appeal of a popular classic. Read more

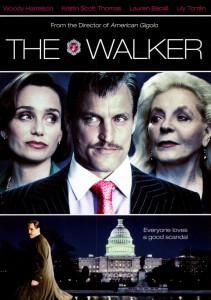

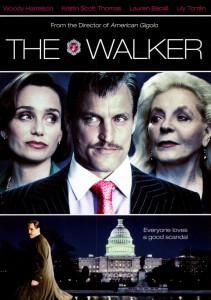

From the Chicago Reader (October 5, 2007). — J.R.

“Has there ever been a good Paul Schrader film?” a colleague asked me on my way into the press screening for this feature, the director’s 16th. I haven’t seen quite all of them, but I couldn’t come up with a single title, even though some have their compensations (Patty Hearst, Light Sleeper). As does this weak thriller, about a gay southern dandy (Woody Harrelson) who escorts aging society ladies around Washington, D.C., and becomes the prime suspect when the lover of one gets murdered. The main compensation is Harrelson’s well-judged and finely shaded performance; the secondary ones are the ladies he hangs out with — Lauren Bacall, Lily Tomlin, and Kristin Scott Thomas. But the rest of this mainly drifts. R, 107 min.

Read more

Read more