The following interview by Sara Donoso, printed in Spanish and English in Fotocinema no. 14 (2017), was conducted in Santiago de Compostela while I was serving on the jury of Curtocircuíto, the international festival of short films held there. I’ve taken the liberty of lightly revising Donoso’s English, and I’ve also retained her Spanish introduction.– J.R.

THE EXPANSION OF CRITICISM: AN INTERVIEW WITH JONATHAN ROSENBAUM

Sara Donoso

Universidad de Santiago de Compostela, España

saradonosocalvo@gmail.com

Crítico, ensayista y teórico de cine, la pluma de Jonathan Rosenbaum es de aquellas que practican el ejercicio de la resistencia; que se oponen a la clasificación, las etiquetas, al mundo del mainstream y a la cultura del espectáculo. Podríamos decir que es uno de esos críticos tal vez incómodos para algunos pero necesarios y reveladores para quienes aprecian el séptimo arte. Tras trabajar como principal crítico del Chicago Reader entre 1987 y 2008, actualmente sigue ejerciendo el ejercicio de la escritura cinematográfica a través de su página web, en la que no solo postea periódicamente reseñas de libros o películas sino que cuenta además con un archivo de publicaciones anteriores.

Como autor y editor, ha contribuido a través de diferentes proyectos a la difusión y dignificación del cine más allá de los circuitos comerciales, siendo responsable de títulos como Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia (2003),Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons (2004) o Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia: Film Culture in Transition (2010). Read more

This appeared in the August 21, 1998 issue of the Chicago Reader. –J.R.

Nights of Cabiria

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed by Federico Fellini

Written by Fellini, Ennio Flaiano, Tullio Pinelli, and Pier Paolo Pasolini

With Giulietta Masina, Franca Marzi, Francois Perier, Amedeo Nazzari, Dorian Gray, and Aldo Silvana.

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

Reporting on the response to Federico Fellini’s Nights of Cabiria at Cannes in 1957, François Truffaut wrote, “Let us deplore the fad that seems to be shared equally by the audience, producers, distributors, technicians, actors, and critics who fancy that they can contribute to the ‘creation’ of the films being shown by deciding how they should have been edited and cut. After each showing, I’d hear things like ‘Not bad, but they could have cut a half-hour,’ or ‘I could have saved that film with a pair of scissors.'” As festival responses to more recent masterpieces like Taste of Cherry and The Apostle have shown, this fad is still very much with us. Another, more recent fad is to release longer versions of films that were butchered on their release. Too often these so-called director’s cuts — such as Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid and the forthcoming Touch of Evil — can’t qualify as restorations, however, because the directors were never accorded final cut in the first place. Read more

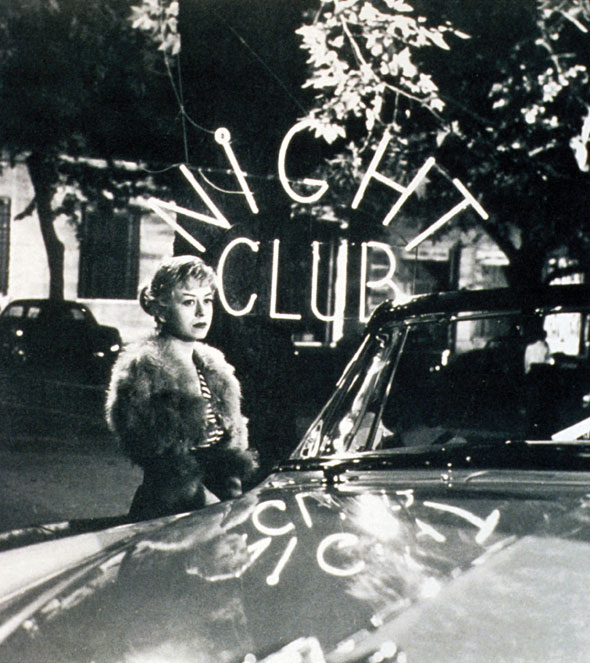

This may be Antonioni’s most unjustly neglected fiction feature, at least in the U.S. (though even in France, where it’s on DVD, it’s only available in a box set). I reviewed it for the May 1975 issue of Monthly Film Bulletin. –J.R.

Signora Senza Camelie, La

(The Lady Without Camelias)

Italy, 1953 Director: Michelangelo Antonioni

If it lacks the final fusion of purposes characterizing a masterwork, La Signora Senza Camelie is nevertheless so unmistakably and remarkably the work of a master that one is shocked to discover the rather cursory critical treatment is has generally been accorded. A frequent bone of contention is Lucia Bosè’s performance as the starlet in search of an identity –- recalling that the part was first offered, in turn, to Gina Lollobrigida and Sophia Loren, and usually implying some difficulty in accepting Bosè as a persuasive Milanese-shopgirl-turned-sex-symbol. Yet what strikes one at once today is how totally her cold, somewhat remote beauty establishes and “places” the tone of the film, clarifying her cosmic distance from the brassy world of popular filmmaking as well as the natural way in which she might become the goddess of such a realm. In anticipation of Godard’s Vivre sa vie, Antonioni brilliantly opens the film with an image of Clara seen from behind, as an anonymous pedestrian -– tracing her fingers across a move poster and then strolling down the street, the camera gliding slowly after her until she turns into the cinema entrance. Read more