It seems that class anxiety has become Woody Allen’s key and obsessive theme ever since his movies started to become “serious”, and it’s usually around in some form even in the purer comedies. Indeed, almost all of the cultural concerns of his work wind up having something to do with class issues — almost as if Allen really believed the crazy American myth that espresso and wealth are inextricably interconnected. The main fantasy about expatriate American bohemians in Midnight in Paris isn’t really about art; it’s about Hemingway or somebody like that stepping into a cab and not worrying about having to pay the driver (which F. Scott Fitzgerald or T.S. Eliot can always take care of), and if Gertrude Stein likes your novel, the bottom line is social acceptance and approval, not artistic license or accomplishment.

From this point of view, Blue Jasmine represents Allen’s coming-out film, by virtue of placing his class anxieties front and center, not through embarking on any themes that are significantly new for him. The vague use of A Streetcar Named Desire (movie and play) as a loose model, with Cate Blanchett serving as a sort of Yankee Blanche DuBois, parallels the vague uses of A Place in the Sun and An American Tragedy in Match Point. Read more

From the June 4, 1999 Chicago Reader. A lot of the material here subsequently turned up in my book Movie Wars. — J.R.

The Thirteenth Floor

Rating * Has redeeming facet

Directed by Josef Rusnak

Written by Rusnak and Ravel Centeno-Rodriguez

With Armin Mueller-Stahl, Craig Bierko, Gretchen Mol, Vincent D’Onofrio, Dennis Haysbert, and Steven Schub.

“I think, therefore I am,” reads the opening epigraph of The Thirteenth Floor, followed by the quotation’s source, “Descartes (1596-1650).” It’s an especially pompous beginning for a movie whose characters barely think, much less exist, but not too surprising given the metaphysical claims and pronouncements that usually inform virtual-reality thrillers.

This is the fourth such thriller I’ve seen in as many weeks, and if any thought at all can be deemed the source of these pictures cropping up one after the other — with the exception of David Cronenberg’s eXistenZ, a film with more than generic commercial kicks on its mind — it might be an especially low estimation of what an audience is looking for at the movies. The assumed desire might be expressed in infantile and emotional terms: “I don’t like the world, take it away.” In other words, for filmmakers stumped by the puzzle of how to address an audience assumed to be interested only in escaping without reminding them of what they’re supposed to be escaping from, virtual-reality thrillers seem made to order. Read more

One wouldn’t expect Albert Brooks’s first novel (Twenty Thirty: The Real Story of What Happens to America) and Woody Allen’s latest movie (Midnight in Paris) to have much in common, especially after one considers that the former is set 19 years in the future whereas the latter is set at least partially between eight and nine decades in the past. But the main thing they do have in common is in fact very contemporary — a preoccupation with money, which Brook’s novel is especially up front about. Both are also ultimately more interested in wisdom than in laughs (or, for that matter, in literature, at least for its own sake); Brooks’s own form of humor, which he seems to find impossible to suppress, is mainly a creative form of sarcasm, which he plants in many of his characters (all of them male, as it happens); more generally, much of his novel’s tone is fairly dour and cautionary. And the principal thing it’s dour and cautionary about is a very contemporary preoccupation with not having enough money. Read more

From the March 1, 1993 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

What the world wanted from Fellini’s epic account of the famous 18th-century lover (Donald Sutherland) was hardly the dark, disturbingly jaundiced, alienated view of eroticism offered here (1976). But as one of the late flowerings of the director’s claustrophobic studio style at its most deliberately artificial, this is a memorable work, helped along by Nino Rota’s music and Danilo Donati’s Oscar-winning costumes. With Tina Aumont, Cicely Browne, John Karlsen, Carmen Scarpitta, and Clara Algranti. (JR)

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 1, 1993). — J.R.

Although I have no facts to support my impression, this erotic courtroom thriller looks as if it grew out of Madonna seeing Basic Instinct and saying, I wanna do one of those. Unfortunately, whatever the limitations of the earlier film, you can’t really do one of those without narrative punch and sweep, which director Uli Edel (Last Exit to Brooklyn) doesn’t manage to muster. While he may be marginally better at directing kinky sex scenes than Instinct‘s Paul Verhoeven, he’s stuck with a fairly ho-hum script by Brad Mirman — millionaire dies of heart failure after sex with his dominatrix girlfriend, who’s charged with murder after inheriting most of his fortune — as well as a performance by Madonna herself that tends to be awkward and unactorly whenever she has to deliver more than a couple of lines at a time. One’s attention is held but not exactly galvanized, even with the combined efforts of Willem Dafoe (the dominatrix’s defense lawyer), Joe Mantegna (the DA), Lillian Lehman (a black woman judge), Anne Archer, and Julianne Moore, not to mention Jurgen Prochnow and Frank Langella in smaller and slimier parts. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 16, 2003). — J.R.

From the Other Side **** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Chantal Akerman.

Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me.

I lift my lamp beside the golden door.

— from “The New Colossus” by Emma Lazarus, quoted on a plaque at the Statue of Liberty

More than 25 years ago, when I was living in a beachside bungalow in a suburb of San Diego, I eventually realized that the bungalow across the alley was a halfway house for Mexicans who’d just made it across the border. I had to figure this out on my own because none of my neighbors ever even alluded to the place or what it was. The constant arrival and departure of new faces was perfectly obvious yet completely unacknowledged—in fact, everything in the surrounding Elysian landscape seemed to encourage one not to observe it. The halfway house was there but not there, like the Mexican ghettos in other parts of suburban San Diego — too decorous to prompt a second look. If people needed to go there in search of cheap labor, they concentrated on what they were looking for. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 1, 2004). — J.R.

Los Angeles Plays Itself **** (Masterpiece)

Directed and Written by Thom Andersen

Narrated by Encke King

I think there’s this weird thing at work now with the way people relate to, specifically, mainstream cinema. When they watch those movies they like to be on the receiving end. . . . The sound is so loud, and the images are so powerful, they want to be totally passive. But then, a few months later, the same film is on DVD, and they can watch it and they own it. And the relationship is inverted. They own that moment, that scene. They also control that diverse, complex relationship they have with film actors. They can watch this or that in slow motion or image by image. — Olivier Assayas in a 2003 interview

The paradigmatic shift in moviegoing described above is fundamental, profoundly altering what we mean by film history as well as film criticism. But if you keep your focus trained on theatrical releases, and regard the subsequent surfacing of the same items on video and DVD only as faint echoes, you’re less likely to be aware of what’s been happening lately, which is in fact affecting the entire corpus of cinema and our access to it. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (November 26, 1993). — J.R.

DEMOLITION MAN

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed by Marco Brambilla

Written by Daniel Waters, Robert Reneau, and Peter M. Lenkov

With Sylvester Stallone, Wesley Snipes, Sandra Bullock, and Nigel Hawthorne.

FEARLESS

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed by Peter Weir

Written by Rafael Yglesias

With Jeff Bridges, Isabella Rossellini, Rosie Perez, Tom Hulce, and John Turturro.

MY LIFE

** (Worth seeing)

Directed and written by Bruce Joel Rubin

With Michael Keaton, Nicole Kidman, Bradley Whitford, Queen Latifah, Michael Constantine, and Haing S. Ngor.

With the steady rise of committee moviemaking and the steady shrinking of attention spans thanks to TV, suspension of disbelief and densely imagined fictional worlds are becoming scarce commodities in pop movies. A relative triumph of style and blackout wit like Addams Family Values reflects this loss just as much as an airhead, cyberdolt, kick-ass romp like Demolition Man. In both films a character’s behavior or personality — and sometimes even the physical terrain — can change radically from one scene to the next, and no one in the audience is expected to notice or even care.

The only thing that seems to be important is that the scene (or moment) score. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 8, 1993). — J.R.

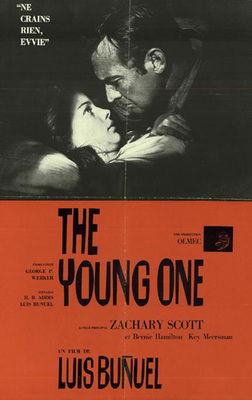

THE YOUNG ONE

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Luis Buñuel

Written by “H.B. Addis” (Hugo Butler) and Buñuel

With Zachary Scott, Bernie Hamilton, Key Meersman, Crahan Denton, and Claudio Brook.

Let’s start with a dream scenario, a movie that might have been. What if Luis Buñuel had made a picture with an American producer, American screenwriter, and American actors during the height of the civil rights movement and set it in the rural south? What if the main character were a black jazz musician from the north fleeing from a lynching, falsely accused of raping a white woman? And, to make a still headier brew, what if Buñuel decided to work in the theme of Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, a recent best-seller — the deflowering of a young girl by a middle-aged man?

As a piece of exploitation, this hypothetical project fairly sizzles; yet in the hands of a poetic, corrosive, highly moral filmmaker like Buñuel, it could well transcend this category. Allowing for the strangeness that would naturally arise from a foreign director taking on such volatile American materials — indeed, a strangeness that might even enhance the freshness of his treatment — one could well anticipate the beauty and excitement such an encounter might produce. Read more

From Cinema Scope, Winter 2005, issue 21. Much of this column is out of date — starting with the URL in the first sentence, which none the less does take you somewhere that’s related. — J.R.

My most fruitful recent discovery for ordering rare films on DVD is www.superhappyfun.com — a mysterious U.S.company whose name sounds oddly Japanese and who makes its own Region 0 DVD-Rs (“a movie that’s been ported over from VHS, tweaked with a time-based corrector, and recorded onto a consumer-grade DVD”), packed in envelopes rather than boxes to save costs and usually priced at $13 apiece. The prints used vary in quality and are ranked in their catalogue entries between 10 (best) and 4 (worst); I’ve found so far that anything below 7 borders on the dubious (such as my blotchy albeit subtitled copy of Jacques Rivette’s Paris Belongs to Us, assigned a 6).

Among the treasures I’ve recently acquired are Edward Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day (the full version, with English subtitles, on two discs, for $15), The Exterminating Angel subtitled, The Girl Can’t Help It letterboxed, a couple of restored Ernst Lubitsch musicals (Monte Carlo and One Hour with You), Joseph Losey’s M, Jacques Tourneur’s Nightfall, Kinugasa’s A Page of Madness (which has no intertitles, so subtitles aren’t needed), Fuller’s Park Row, and Antonioni’s The Passenger. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 1, 1998). — J.R.

The Japanese title literally means “not yet,” a child’s response to the query “Are you ready?” in a game of hide-and-seek, and Akira Kurosawa’s 1993 film is his own way of saying the same thing. Written and directed by Kurosawa at age 83, this very personal film, set between 1943 and about 20 years later, concerns a retired professor (Tatsuo Matsumura), his circle of adoring former students (all male), his cat, and his wife. It?s full of moving moments, but unlike the exquisite Rhapsody in August (1991) it can’t be regarded as major Kurosawa. Basically a series of sketches drawn from the writings of Hyakken Uchida, the film periodically calls to mind John Ford’s The Long Gray Line as an extended valediction (one long birthday gathering seems to go on forever). Madadayo has the expressionistic simplicity of Kurosawa?s other late films, their distillation and intensity of emotion; one of the lengthiest episodes, about the loss of the hero’s cat, is especially powerful. There’s something undeniably hermetic and at times sluggish about the film’s style, but the sheer freedom of the discourse—the way Kurosawa inserts brief flashbacks into the narrative whenever he feels like it or ends the movie with a dream—is comparable in some ways to late Buñuel, and the film shares his poignant sense of wonder. Read more

From Cineaste, Fall 2003. — J.R.

Paris Hollywood: Writings on Film

by Peter Wollen. London and New York: Verso, 2002. 314pp. Hardcover: $60.00 and Paperback: $20.00.

One of the more interesting paradoxes of Peter Wollen’s writing career is that he was perceived as an academic well before he had a long-term teaching post whereas today, with a seemingly permanent berth in the critical studies program at UCLA’s film department, he’s more apt to come across as a journalist. Part of this has to do with the magazines he writes for, though it might be added that for better and for worse — and more for the better — there’s always been a breezy, nonpedantic side to his writing that makes it far more accessible and user-friendly than the work of many of his more theoretically-minded colleagues. Paris Hollywood, his latest collection, is an agreeable showcase for this quality — more so, in many ways, than Readings and Writings (1982) and Raiding the Icebox (1993).

There are, to be sure, some scholarly limitations to Wollen’s lightness of tone, at least when he falls too readily into certain easy generalizations. It may sound reasonable to write of Godard’s early work (in “JLG,” one of the better essays here), “He never once worked with a script-writer,” but only if one glides past the roles of Truffaut on Breathless and Rossellini and Jean Gruault on Les Carabiniers. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (September 23, 1994). — J.R.

QUIZ SHOW ***

(A must-see)

Directed by Robert Redford

Written by Paul Attanasio

With Rob Morrow, Ralph Fiennes, John Turturro, David Paymer, Christopher McDonald, Elizabeth Wilson, and Paul Scofield.

Behind the opening and closing credits of Quiz Show we hear two different pop versions of “Mack the Knife” — Bobby Darin’s bright, Lyle Lovett’s funereal — perhaps an indication that director Robert Redford has something faintly Brechtian in mind. If so, probably the most relevant Brecht passage is the exchange that concludes the 12th scene of Galileo, when Andrea, the son of Galileo’s housekeeper, quotes the maxim “Unhappy is the land that breeds no hero.” Galileo replies, “No, Andrea: ‘Unhappy is the land that needs a hero.'”

On the other hand, this is Robert Redford we’re talking about, who’s been a hero in this unhappy land for the past three decades, not someone who’s ever been known to seriously rock any boats. A better indication of what makes Quiz Show so interesting, suggestive, and fruitful (if not Brechtian) is the showroom spiel for a glittering Chrysler 300 given to the movie’s hero, congressional investigator Richard N. Goodwin, shown out shopping just before the opening credits. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 1, 1996). — J.R.

A little over two hours of recent videos by the great essayistic filmmaker Chris Marker (Sans soleil), ranging from playful personal works — such as Bestiary, put together between 1985 and 1993 and consisting of a record of the filmmaker’s cat’s responses to Ravel, the repeated staring of an owl, and two separate videos shot at a zoo — to documentaries for European television, including one that features Andrei Tarkovsky shooting the last sequence of his last film and then watching the film on video from his sickbed, a playful 1988 tour of Tokyo streets, a 1990 survey of reunified Berlin, a monologue by the painter Roberto Matta about his own work, and a fascinating account of a community of Bosnian refugees in Slovenia pirating TV signals to watch the news together. The videos about Tokyo, Berlin, and Tarkovsky aren’t subtitled, but they’re still highly watchable (and they contain bits of English, including actress Arielle Dombasle’s charming imitation of an American accent in the Tokyo work). The overall experience is roughly akin to channel surfing in a European hotel with a satellite dish. (JR)

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 1, 1993). — J.R.

A revisionist look at the last 67 days of Vincent van Gogh’s life by the highly talented writer-director Maurice Pialat (The Mouth Agape, A nos amours, Under Satan’s Sun), with singer-songwriter-actor Jacques Dutronc — the Bob Dylan of Paris and the lead in Godard’s Every Man for Himself — in the title part. Ironically, this 155-minute French art movie shows the painter’s existence, including his sex life, to be a lot happier than is generally depicted — much sunnier, in fact, than Vincente Minnelli’s or Robert Altman’s films on the same subject; in any case, it certainly qualifies as a personal work. (The period re-creations of Jean Renoir and John Ford remain the key reference points.) While the results shed little light on van Gogh’s painting, some painters I know are smitten with this film, and the mise en scene and the period flavor are both quite remarkable. With Alexandra London, Gerard Sety, Bernard le Coq, Corinne Bourdon, and Elsa Zylberstein (1992). In French with subtitles. (JR)

Read more

Read more