From the December 22, 1989 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

List in the Pocket

With both a year and a decade now drawing to a close, the number of lists indicating the best and the most seems greater than ever. So pronounced, in fact, is this listomania concerning the 80s that in many cases it had already moved into full gear by late October, while the decade still had a good nine or ten weeks to go. The Tribune‘s Sunday arts section, for example, got its critics to come up with their ten-best lists for the 80s in time for an October 22 publication date, while the movie magazines Premiere and American Film, which plan their issues much further in advance, hit the stands with their own hit parades in early November.

Should we attribute these premature evaluations to a general eagerness to have the 80s over and done with? Whatever the reason, a recent movie list issued by Baseline, “the entertainment industry’s information service,” based in New York and Beverly Hills, offers some additional causes for gloomy reflection. The list in question gives us “the top ten turkeys of the 80s.”

Talking Turkey

Once upon a time, a “turkey” was a bad film, and a movie that lost money was a “bomb.” Read more

From the June 10, 1988 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

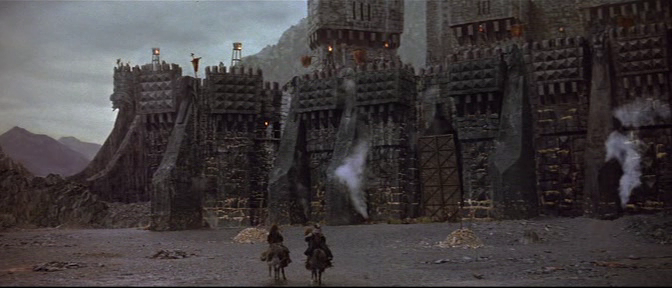

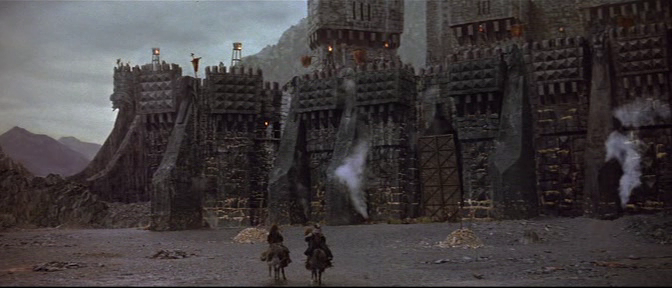

WILLOW

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed by Ron Howard

Written by Bob Dolman and George Lucas

With Val Kilmer, Joanne Whalley, Warwick Davis, Billy Barty, Gavan O’Herlihy, Jean Marsh, Pat Roach, and Patricia Hayes.

As one of those spoilsports who actively disliked Star Wars when it burst on the scene 11 years ago, enjoyed The Empire Strikes Back (1980) even less, and happily managed to miss both Return of the Jedi (1983) and Labyrinth (1986), I can’t say that I approached George Lucas’s latest ecumenical blockbuster with expectations of much pleasure. Nevertheless, now that his latest fantasy epic has confirmed my nonexpectations, I can’t help but wonder why Willow has been getting such a drubbing from the same reviewers who responded to the early Lucas mega-hits with such enthusiasm. Is it really all that different from its predecessors?

Lucas’s reputation seems to be passing through the same sort of vicissitudes as Ronald Reagan’s: a few years of euphoric tub thumping while the future was getting steadily sold away under our feet, followed by recriminations and icon bashing, which seem motivated less by second thoughts than by certain automatic principles built into an economy of planned obsolescence. Read more

The first and last parts of what follows are taken (and in a few cases adapted) from my book Discovering Orson Welles. — J.R.

In spite of my five years of living in Paris, my grasp of French has always been mediocre — a weakness that over the years I’ve come to regard as a sort of disability, because I’ve made many efforts to overcome it. That François Truffaut had a similar (and similarly embarrassing) problem with his English set the stage for a rather awkward and uncomfortable afternoon in London between the two of us — with his assistant Suzanne Schiffmann often serving as mutual interpreter — after I’d signed with Harper & Row to carry out a translation of Bazin’s book on Welles, as well as a new Foreword to that book that Truffaut was writing. Truffaut undoubtedly came away from that afternoon with some understandable skepticism about why I’d been hired to do this job, while I emerged, somewhat defensively, with the impression that he was closer to being a nervous and irritable businessman than the sort of critic and director that I had formerly revered.

I hasten to add that I wasn’t bluffing when I’d praised in print Bazin’s 1950 monograph on Welles in 1971 as the best criticism published about him —- or at least not entirely. Read more

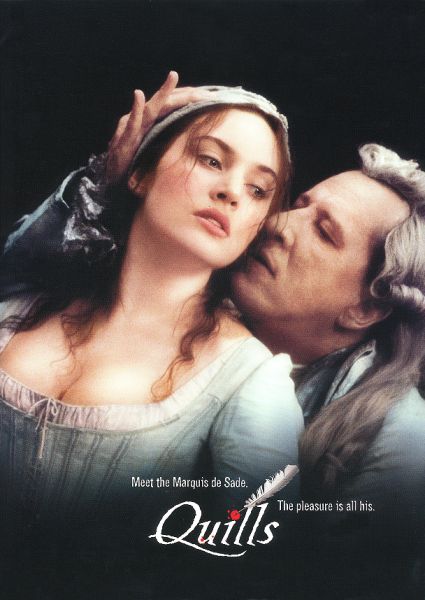

From the December 15, 2000 issue of the Chicago Reader. — J.R.

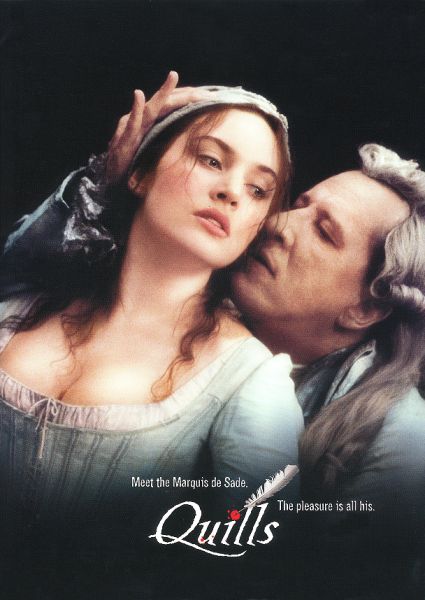

Quills

***

Directed by Philip Kaufman

Written by Doug Wright

With Geoffrey Rush, Kate Winslet, Joaquin Phoenix, Michael Caine, Billie Whitelaw, Patrick Malahide, and Amelia Warner.

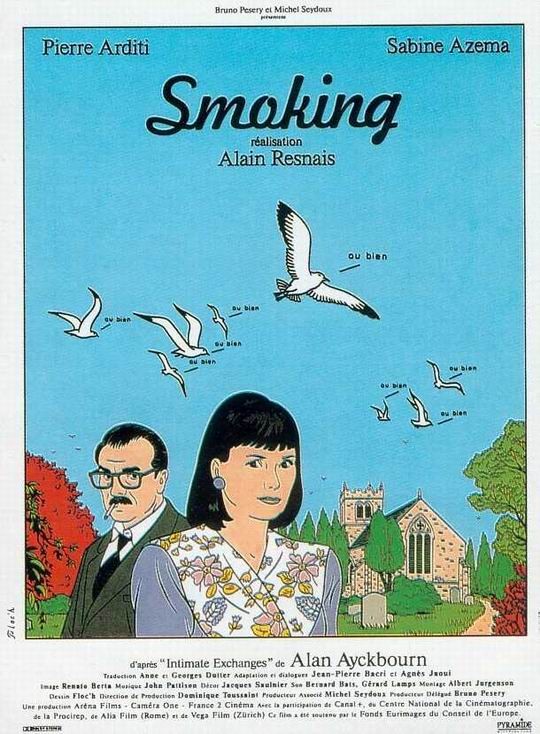

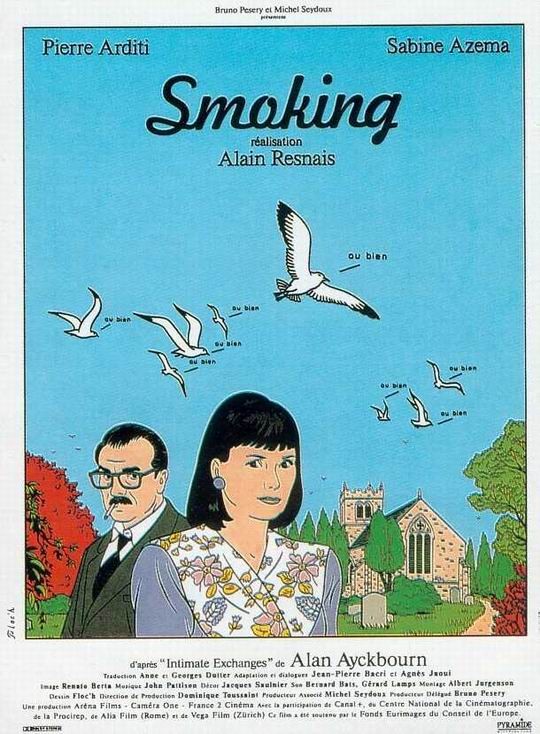

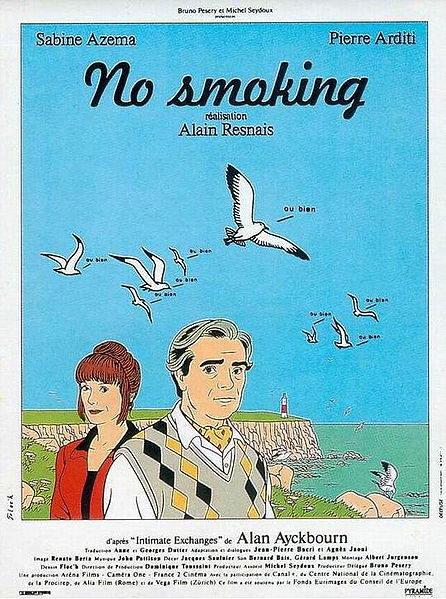

Smoking

***

Directed by Alain Resnais

Written by Alan Ayckbourn, Jean-Pierre Bacri, Agnès Jaoui, and Anne and Georges Dutter

With Pierre Arditi and Sabine Azéma.

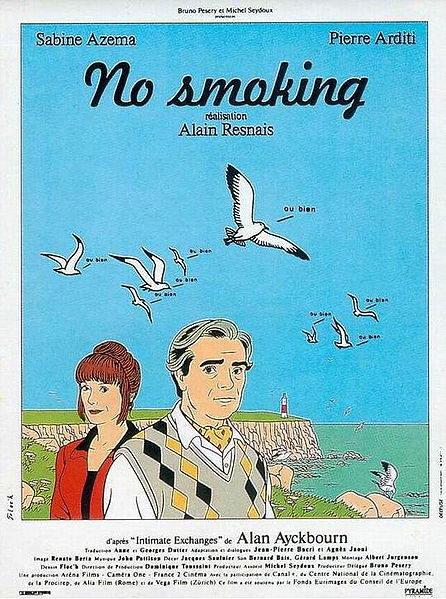

No Smoking

***

Directed by Alain Resnais

Written by Alan Ayckbourn, Jean-Pierre Bacri, Agnes Jaoui, and Anne and Georges Dutter

With Pierre Arditi and Sabine Azema.

Quills is an American adaptation of an American play about the famous 18th-century French libertine the Marquis de Sade, starring Australian, English, and American actors. It is also, in part, an unacknowledged mainstreaming of a more intellectual German play that became famous in the mid-1960s because of an exciting and inventive staging by avant-garde English director Peter Brook — Peter Weiss’s The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton Under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade, popularly known as Marat/Sade. (Brook’s 1966 film adaptation of this intensely theatrical play is a pale shadow of the original.)

Smoking and No Smoking — not a double bill but a pair of interactive features that can be seen in either order, both playing at Facets Multimedia Center this week — are French adaptations of a cycle of eight mainly comic English plays by Alan Ayckbourn. Read more

This originally appeared in the August 15, 2003 issue of the Chicago Reader. — J.R.

The Gatekeeper — produced, directed, and written by someone you’ve never heard of, with a cast that’s equally unknown — is a realistic, no-nonsense independent feature about Mexican immigrants enslaved just after crossing illegally into the U.S. Masked and Anonymous — a Bob Dylan vehicle packed with stars, directed by a sitcom veteran, and produced by the BBC — is a fantasy about a legendary singer giving a benefit concert for wounded counterrevolutionaries in a slum-infested city where the country’s dictator is dying.

These movies have little in common, apart from being grim commentaries on the corruptions of the American dream that use impoverished southern California locations. Yet I had the same sensation after seeing each of them: I felt I’d just received a jolt of contemporary reality, something I rarely can say about commercial movies nowadays.

Even if only indirectly, both movies have something to say about global warming and the depletion of the ozone layer, government and crime, the torrents of spam flooding e-mail accounts, the relentless aggression of telemarketing, the political chaos in Iraq and other places (including California), the misery of the poor and homeless, and the almost random casualties arising from heat-crazed and trigger-happy cops and soldiers surrounded by people who despise them. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (September 1, 1995). — J.R.

Beyond Rangoon

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by John Boorman

Written by Alex Lasker and Bill Rubenstein

With Patricia Arquette, U Aung Ko, Frances McDormand, Spalding Gray, Tiara Jacquelina, and Victor Slezak.

Reviewing Salvador Dali’s autobiography half a century ago, George Orwell wrote that Dali “grew up in the corrupt world of the 1920s, when sophistication was immensely widespread and every European capital swarmed with aristocrats and rentiers who had given up sport and politics and taken to patronizing the arts. If you threw dead donkeys at people, they threw money back.” Offended by the sort of sophistication that he associated with mindless tolerance, Orwell recorded his own puritanical outrage at the brutal shenanigans of Dali and his apologists: “It will be seen that what the defenders of Dali are claiming is a kind of benefit of clergy. The artist is to be exempt from the moral laws that are binding on ordinary people. Just pronounce the magic word ‘art’ and everything is OK. Rotting corpses with snails crawling over them are OK; kicking little girls on the head is OK; even a film like L’age d’or is OK.”

Unfortunately, Orwell hadn’t seen Buñuel’s 1930 masterpiece and had been misinformed about it; it’s subsequently been demonstrated that, contrary to popular belief, Dali had little to do with it. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 6, 1988). — J.R.

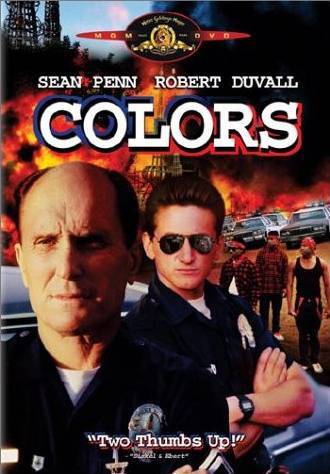

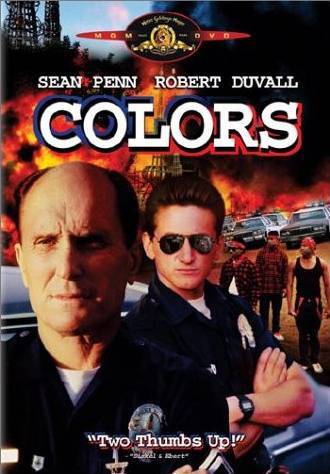

COLORS

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Dennis Hopper

Written by Michael Schiffer and Richard Dilello

With Sean Penn, Robert Duvall, Maria Conchita Alonso, Randy Brooks, Grand Bush, Don Cheadle, Glenn Plummer, and Rudy Ramos.

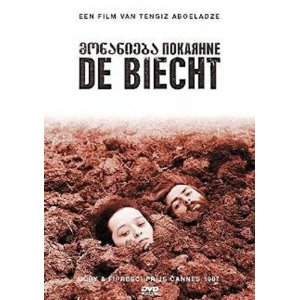

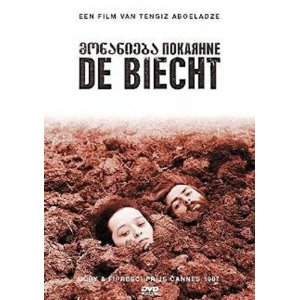

REPENTANCE

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Tengiz Abuladze

Written by Nana Djanelidze, Tengiz Abuladze, and Rezo Kveselava

With Avtandil Makharadze, Zeinab Botsvadze, Ketevan Abuladze, Edisher Giorgobiani, Kakhi Kavsadze, Iya Ninidze, and Merab Ninidze.

For several weeks now, I’ve been trying to get a fix on what irritates me so much about Colors. Seeing it again recently, and then seeing Repentance for the first time the next day, a few hours before I started this review, gave me the beginning of an answer, and it isn’t a pretty one. If these films can be said to represent what “social criticism” currently means in the respective cultures of the U.S. and the Soviet Union — and, after a certain amount of boiling and scraping, I think that they can — then it seems to me we’re in trouble.

It’s been estimated that over 60 million Russians have already seen Repentance, the most prominent of all the belated, post-glasnost Soviet releases — scripted in 1981-82, filmed in 1984, and apparently shelved for only two years prior to the thaw. Read more

I no longer recall where this was written for and/or published, but I’m pretty sure it was written in 2004. Eight years later, having just seen Far from Afghanistan at the Toronto film Festival — a film that John Gianvito organized, shot a portion of, and edited, playing a role somewhat comparable to that of Chris Marker on Far from Vietnam — I’m reminded yet again of how irreplaceable and precious John is to to the conscience and, yes, endurance of American cinema. — J.R.

A rare act of bearing witness, The Mad Songs of Fernanda Hussein is the only film I know that gives ample voice to the rage and despair felt by many Americans during the Gulf war —- a loose, disparate, disorganized, and virtually invisible group of individuals in which I’d include myself. Many of us are experiencing comparable emotions at the moment, after September 11 and the terrifying fantasies of consensus that have followed, most of them involving present and future American invasions and conquests.

All this gives John Gianvito’s 168-minute feature an urgency that he couldn’t have anticipated when he finished the film early last year. It also makes me feel grateful personally, in a way that goes beyond critical approval, if only because it proves to me and several others that we aren’t alone. Read more

My latest column for Caiman Cuadernos de Cine:

Two signs of hope in an era often defined by hopelessness:

(1) After a half century of prevarication, media has finally gotten around to calling Donald Trump a gangster, thanks to the 34 accusations of “racketeering” in his Georgia indictment, thus forever altering his media profile.

(2) An experimental, intellectual essay film (and comedy), Greta Gerwig’s Barbie, has become a world-wide hit, thanks in part to its audience not perceiving it as such. Thus a belated form of truth-telling in politics occurs around the same time as an effective form of subterfuge in cinema.

A century ago, audiences had far less difficulty calling Al Capone a gangster and perceiving F. W. Murnau’s Der letzte Mann as some sort of experimental and intellectual essay film, largely because they hadn’t received as much conditioning from publicists as we’ve had, to hate and mistrust films addressing our intellects.

A federal law in the U.S. known as the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act and a highly successful line of dolls for little girls have helped to set the stage for these surprising recent developments. Furthermore, Capone arguably had some edge over Trump due to his taste for culture (e.g., Read more

From the Chicago Reader (September 29, 1995). — J.R.

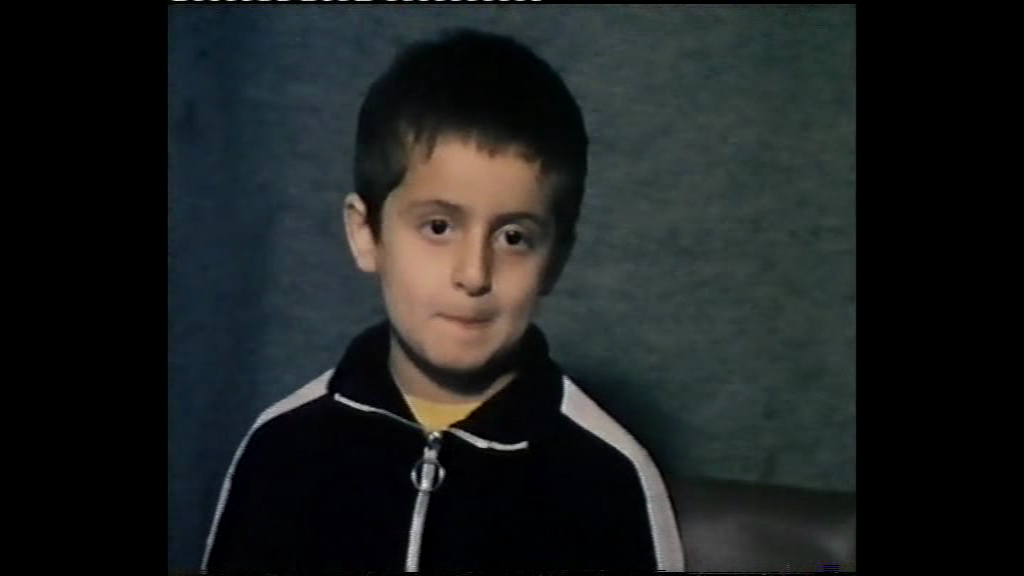

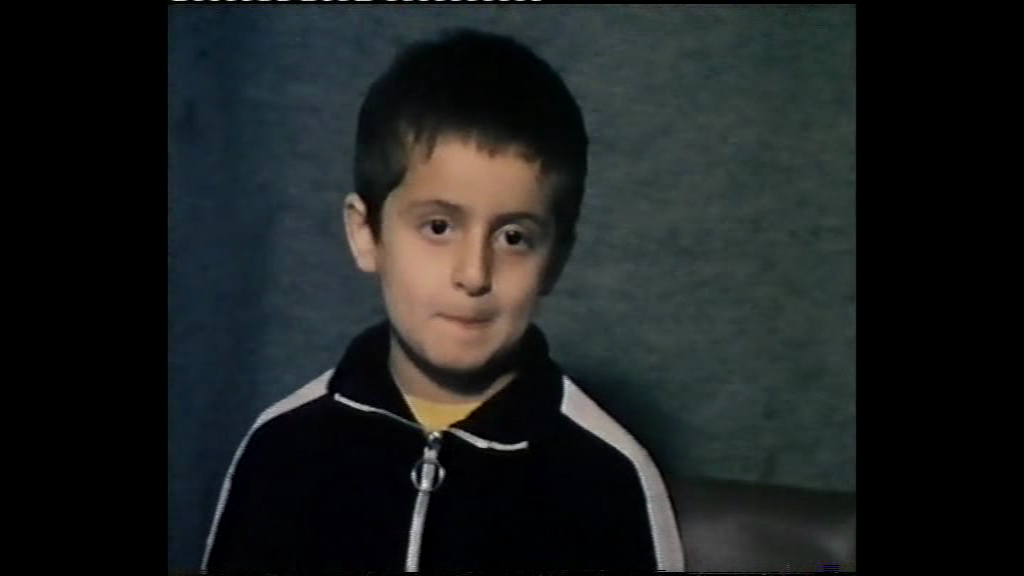

Homework

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Abbas Kiarostami

Through the Olive Trees

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Abbas Kiarostami

With Hossein Rezai, Tahereh Ladanian, Mohamad Ali Keshavarz, Farhad Kheradmand, and Zarifeh Shiva.

At the Toronto film festival earlier this month Canadian filmmaker Clement Vigo recalled the memorable response of Winston Churchill to pressure to cut state arts funding during World War II: “If we cut funding for the arts and culture, then what are we fighting for?” It’s a question I’ve been pondering ever since.

A month earlier, while I was in the middle of looking at close to 100 films as part of the New York film festival’s selection committee, I had the rare privilege of being able to fly for a weekend to still another festival, in Locarno, Switzerland, to serve on a panel devoted to Godard’s Histoire(s) de cinéma. Locarno had two ambitious sidebars this year — one devoted to Godard’s video series, the other to Iranian women filmmakers and the first virtually complete retrospective of work by Iranian master Abbas Kiarostami ever held anywhere, including an exhibition of his color photographs of landscapes and two very beautiful paintings. Read more

All of those who can find or make no meaningful distinction between the following two sentences — “The world is going to hell in a handbasket”; “America is going to hell in a handbasket” — are likely to find an article called “The Cecil B. De Mille of Movie Lists” by Stuart Miller, featured prominently in the Arts and Leisure section of today’s New York Times, precisely the sort of entertaining news that intelligent movie lovers should be paying close attention to. I’ll try to oblige them.

The article celebrates (and perpetuates) the untiring efforts of a produce clerk in Austin, Texas to list the 9,200 greatest movies ever made, a project clearly viewed by Miller as the quest of an enlightened primitive. But what could be more primitive than Miller’s own assumption that the clerk’s omission of silent films and animated films is a secondary matter, to be squirreled away in the article’s penultimate paragraph? Or, even worse, that three more minor omissions, apparently equivalent to one another in importance, and clearly even less important than silent and animated films — “documentary, made-for-TV and foreign-language films” — can be acknowledged parenthetically in a follow-up sentence?

I suppose we should all therefore assume, along with Miller and his editors, that foreign-language documentaries, silent documentaries, made-for-TV documentaries, foreign-language TV films, and foreign-language animated films (among other neglected possibilities) are omissions that aren’t even worth mentioning, even in passing, as existing categories. Read more

This was written in the summer of 2000 for a coffee-table book edited by Geoff Andrew that was published the following year, Film: The Critics’ Choice (New York: Billboard Books). — J.R.

Considering how romantic it is, how sad and funny and charming, it is a sobering fact that François Truffaut’s second feature –- and the first one that qualifies as a quintessential New Wave expression — was a disaster at the boxoffice. Indeed, if this eccentric adaptation of David Goddis’s 1956 crime novel Down There illustrated any general commercial principle, this may be that one subverts overall genre expectations at one’s peril. For Tirez sur le pianiste is a film noir that literally turns white (through such images as piano keys or a snowy hillside) when the plot is at its darkest, and one that sometimes interrupts the viewer’s laughter with a disquieting catch in the throat.

The opening sequence already sends out bewildering crossed signals. A man fleeing in panic through dark city streets at night collides with a streetlight, then finds himself talking quite calmly with a sympathetic stranger –- a character who exits the movie immediately thereafter -– about the latter’s love for his wife. Moreover, while the fluid and flexible black-and-white cinematography (by Raoul Coutard) is in the anamorphic process Dyaliscope, the ambience is cramped and cozy in the best low-budget tradition. Read more

This was written in the summer of 2000 for a coffee-table book edited by Geoff Andrew that was published the following year, Film: The Critics’ Choice (New York: Billboard Books). — J.R.

Apart from his scandalous Salò, or the 120 days of Sodom, 1975 -– another film with spiritually induced levitation -– this shocking 1968 feature, Pier Paolo Pasolini’s last film with a contemporary setting, may be his most controversial work, displaying the kind of audacity and excesses that send some audiences into gales of defensive, self-protective laughter. (For a contemporary near-equivalent, think of Bruno Dumont’s 1999 film L’Humanité.)

The “theorem” of the title is a mythological figure whose arrival is heralded by Pasolini’s favorite fetish-actor, Ninetto Davoli, bringing a telegram to the home of an industrialist (Massimo Girotti). An attractive young man in tight-fitting trousers (Terence Stamp) then pays an extended visit, proceeding with solicitous devotion to seduce every member of the household — father, mother (Silvana Mangano), teenage daughter (Anne Wiazemsky), somewhat older son (Andrès José Crux), and maid (Laura Betti) — to the recurring strains of Mozart’s Requiem Mass and a modernist score by Ennio Morricone.

Then the stranger leaves as mysteriously as he came, and everyone in the household undergoes cataclysmic and traumatic changes. Read more

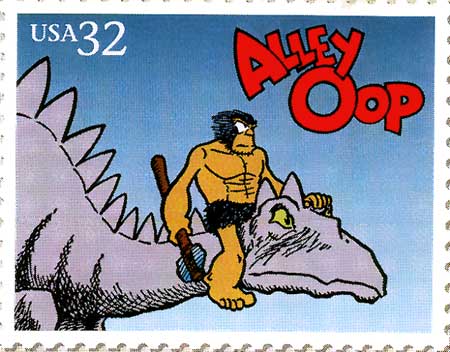

From the Chicago Reader (June 24, 1988). — J.R.

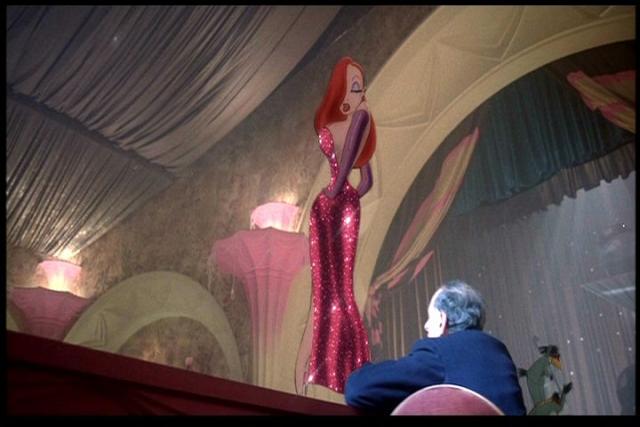

WHO FRAMED ROGER RABBIT

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Robert Zemeckis

Written by Jeffrey Price and Peter Seaman

With Bob Hoskins, Joanna Cassidy, Christopher Lloyd, Stubby Kaye, Alan Tilvern, and the voices of Charles Fleischer and Kathleen Turner.

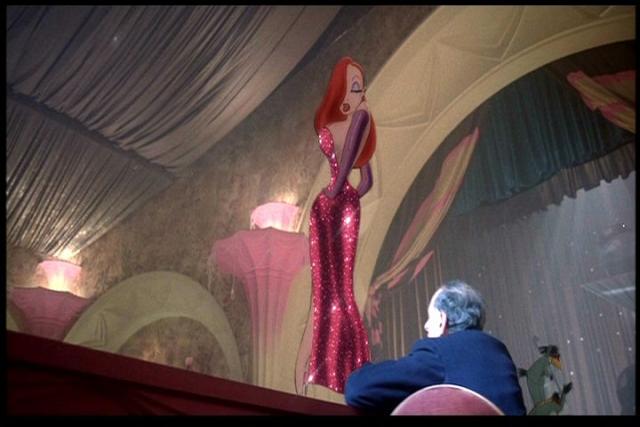

Imagine, if you can, that the characters who appear in animated cartoons actually exist. A repressed minority and endangered species known as Toons, they live on the fringes of Hollywood in 1947 in a ghetto known as Toontown; when they aren’t working for Disney or the other cartoon studios, they take on menial positions as waitresses, bartenders, cigarette girls, bouncers, and entertainers — at a segregated club called the Ink and Paint. (Among the acts at this dive are Donald Duck and Daffy Duck, who perform a duet on two pianos, and a vocalist named Jessica, a curvy vamp who’s a human Toon, accompanied by the bebop crows from Dumbo.)

Imagine, as well, that the live-action 40s Hollywood that these Toons are working in is the world of Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe, or at least that world as it was revised and “updated” by Robert Towne when he scripted Chinatown in the 70s. In the place of Chandler’s Marlowe and Towne’s Jake Gittes is Eddie Valiant (Bob Hoskins), a gumshoe whose jobs are mainly Toon-related, and whose partner and brother Teddy was killed a few years ago when an unknown Toon dropped a piano on the brothers, considerably dampening Eddie’s sense of humor and appreciation of Toons in the process. Read more

From the April 1, 1994 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

* THE HUDSUCKER PROXY

(Has redeeming facet)

Directed by Joel Coen

Written by Ethan Coen, Joel Coen, and Sam Raimi

With Tim Robbins, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Paul Newman, Charles Durning, John Mahoney, Jim True, and William Cobbs.

A black man called Moses but who might as well be named Rastus serves as the narrator for the opening and closing segments of Ethan and Joel Coen’s The Hudsucker Proxy. A janitor type who takes care of the giant clock near the top of the Hudsucker Industries building, an art-deco skyscraper in midtown Manhattan, Moses (William Cobbs) knows everything of importance there is to know about Hudsucker Industries, including all of its secrets. And in case you’re wondering how he knows, the Coen brothers have a ready answer: this is Hollywood, and like every other figure in the movie, Moses is a Hollywood cliché. In old-fashioned studio pictures, black janitors or clock tenders with names like Moses are chock-full of down-home wisdom as well as concrete information about what all those funny white folks is doing.

Resurrecting a racial stereotype like Moses for a 90s comedy may sound dubious, but I suspect the Coens would have an answer to that as well. Read more