From the online Moving Image Source (July 20, 2011), — J.R

Everybody has their own Laurel and Hardy. A miniature Laurel and Hardy, one on each shoulder. Your little Oliver Hardy bawls you out -– he says, “Well, this is a fine mess you’ve gotten us into.” And your little Stan Laurel gets all weepy -– “Oh, Ollie, I couldn’t help it, I’m sorry, I did the best I could….”

— Groucho Marx on LSD

Living in a garbage can be a lot of fun….

Life is always equal in the can….

— the first and last lines of Skidoo’s Garbage Can Ballet

Seeing works of art, including films, in terms of success or failure, smash or flop, can be a form of tyranny, a limiting of options — not to mention a recipe for boredom, especially if one has no monetary stake in the outcome, which is true in most cases. So to say that Otto Preminger’s Skidoo –- which has finally become available on a letterboxed DVD, released by Olive Films -– failed at the boxoffice in 1968 and fails today, as it failed 43 years ago, as a lighthearted comedy, while certainly accurate, may not be the most helpful thing to say about it.

The same goes for the usual charges against Preminger’s vulgarity, especially if one neglects to pinpoint its mannerist nature and its bizarre manifestations, its various effects and/or consequences. In some cases (though by no means all of them), what we mean when we refer to Preminger’s vulgarity is in fact his unbridled curiosity. One example of this curiosity, in Preminger’s underrated 1971 black comedy Such Good Friends (also just out on an Olive Films DVD): James Coco attempting surreptitiously to remove his girdle while Dyan Cannon, in a gesture of despair, prepares to give him a blowjob. A counter-example of unambiguous vulgarity in the same picture: Cannon’s character fantasizing Burgess Meredith dancing in the nude at a rooftop publishing party. Both these examples, to be sure, are contestable, and largely a matter of our own subjectivity as well as Preminger’s.

Whatever we conclude, it might be useful to start a discussion about Skidoo with such problems about commercial viability and taste –- or at least I hope it is, because that’s what I’m doing here. But to end it in the same fashion, as most often happens, is to surrender to a rather tiresome series of tautologies. And to argue that Skidoo is so bad that it’s good, employing what might be termed the ever-popular Edward D. Wood escape clause, might simply be an alternative way of perpetuating the same syndrome.

Skidoo begins with three words — Otto, Preminger, and its own title — accompanied by a cartoon convict floating down with what appears to be a flower, a balloon, and/or an umbrella in his hand, who does a soft-shoe across the three words while treating the flower-balloon-umbrella like a dancing cane. The camera pulls back to show that this is all occurring on the screen of a TV console in a living room in or near what proves to be San Francisco while we hear Carol Channing whining offscreen, in a cartoon voice, “No, Harry, not that. No, Harry, I don’t want to see that. Harr-eeee…” We hear the rapid clicks of a TV remote control, and the image shifts to Peter Lawford presiding over a government crime hearing, which then switches to a sudsy parody of a TV commercial featuring a starlet-bimbo, both of which alternate in turn with panned-and-scanned fragments from Preminger’s In Harm’s Way, another parody of an ad (this one featuring a bottle of beer and a burping pig) while Channing says, “No, Harry, I don’t watch films on TV. They always cut them to pieces,” then still other parodies, including one featuring a dog smoking a cigarette and another that appears to be an NRA spot for guns as a healthy and cheerful family pastime.

All things considered, it’s Preminger’s version of Naked Lunch, complete with cutups, a collage/montage/garbage can equating adult culture circa 1968 with strident corruption and untidy American democracy with confusion, and we’re more than two minutes into the film before we finally get reverse angles of the TV watchers — Channing (Flo Banks), Jackie Gleason (Tony Banks), and the aforementioned Harry (Arnold Stang, clutching the remote control until Tony snatches it away from him) — who are filmed in an overlit suburban living room, dressed respectively in blazing orange, red, and pink, which overpower their flesh tones to such a degree that all three actors look a little bit like cadavers. Then we get two more minutes of channel surfing before we finally settle on the crime hearing, which allows us some exposition about Tony Banks’ former life as a hitman for a mafialike gang lorded over by a character named God (Groucho Marx), and Tony having married Flo (a flighty former dancer) about 18 years ago when she was three months pregnant — occasioning a lot of obsessing on his part about whether or not Darlene (Alexandra Hay), their teenage daughter, is actually his — and the arrival of some members of that gang at his home a few moments later. We also witness a duel between Tony and Flo with their competing TV remote controls.

Thanks to a couple of informative recent critical biographies of Preminger – Foster Hirsch’s Otto Preminger: The Man Who Would Be King (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007) and Chris Fujiwara’s The World and its Double: The Life and Work of Otto Preminger (New York: Faber and Faber, 2008) — we now know quite a bit about the production circumstances of Skidoo. Fujiwara, who rightly points out how personal the film was for Preminger (even the clips from In Harm’s Way allude to Preminger’s unsuccessful lawsuit in 1965-66 to prevent the recutting and fragmentation of his Anatomy of a Murder on TV to facilitate commercial breaks), adds that “Preminger’s two most reviled films [Skidoo and Rosebud] are those about whose productions the most is known.”

We learn from both books that Skidoo emerged from the ashes of Preminger’s prolonged efforts to develop a satisfactory script adaptation of John Hersey’s Too Far to Walk, a novel “about rebellious college students experimenting with drugs” (Hirsch) — an effort that had already led Preminger to take LSD himself, with Timothy Leary serving as his initial guide until he decided to spend the remainder of his trip alone. (Somewhat later, after Groucho Marx was cast as God — by which time this part had been turned down by, among others, Senator Everett Dirksen, Alfred Hitchcock, Zero Mostel, Anthony Quinn, Frank Sinatra, and Rod Steiger — he embarked on an acid trip himself, with Paul Krassner as his guide (an event chronicled by Krassner himself in the February 1981 High Times, available online at sirbacon.org/4membersonly/groucho.htm), occasioning the observation cited above about Laurel and Hardy.

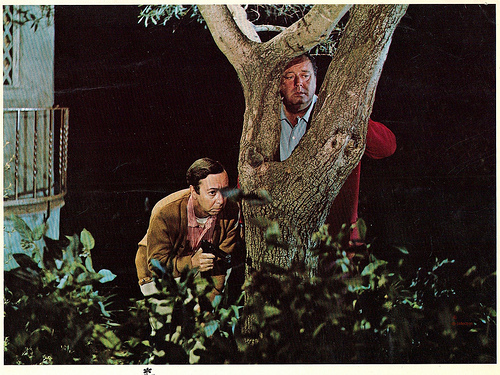

It’s also clear that part of Preminger’s desire to make a “youth” movie was connected to a desire to bond with his illegitimate son with Gypsy Rose Lee, Erik, who was then in his mid-20s and whom Preminger had just started to become acquainted with, hiring him as a casting director on his latest project. After the last of Preminger’s many screenwriters on this same project, Doran William Cannon, submitted as two writing samples his scripts for Brewster McCloud (later filmed by Robert Altman) and Skidoo, Preminger wound up purchasing the latter in October 1967 to replace Too Far to Walk. Another relevant factor was Preminger’s contractual obligation to deliver a feature to Paramount in time for a 1968 release. He wound up casting a good many familiar Hollywood and TV icons as the corrupt adults — apart from those already mentioned, Frankie Avalon, Fred Clark, Frank Gorshin, Burgess Meredith, Slim Pickins, George Raft, Cesar Romeo, and Mickey Rooney — and a slate of relative newcomers as the young hippies, including Alexandra Hay as Darlene — who had recently costarred in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner?, and would later appear in The Model Shop — as well as John Philip Law, who had already appeared in Hurry Sundown (and appeared in Barbarella, around the same time), as her boyfriend Stash, and stage actor Austin Pendleton, in his screen debut, as Tony’s prison cellmate Fred, who turns out to be the movie’s unexpected genius hero.

Fujiwara understandably calls Skidoo “a deeply contradictory film,” but I think the adjectives “conflicted” and “dialectical” may come closer to the mark, accounting in part for the movie’s very peculiar stylistic mixtures of Hollywood slickness, diverse forms of countercultural chaos (such as the casual way that dogs appear to wander at random into a couple of shots), and a penchant for filming all the better-known and older cast members so that they look less like their usual star personas as one becomes uncomfortably aware of their aging bodies, imparting a resonance to the proceedings that is usually far from comic. Indeed, we can’t accuse the movie of lacking in emotional affect, only that the emotions often run against the grain of the intended laughter and cheerfulness. Despite Preminger’s clear desire, in his early 60s, to bridge the generation gap and even to proselytize on behalf of LSD as a drug with revolutionary possibilities — regarding his own generation and class as a pack of cynical, uptight gangsters and the youthful counterculture as a tribe of innocent yet liberated utopians — his jaundiced view of himself as a member of the former camp clearly complicates this scenario. It’s not quite as though the hippies are all heroes and the crooks and/or prudes are all villains, but the latter are chiefly seen as ridiculous (except for Tony Banks, whom, thanks to Gleason’s potent aura of melancholia, we mainly perceive as sad and tormented) while the former are silly at worst, enlightened and resourceful at best (Stash being somewhere in between).

The only truly in-between character (and, arguably, the sanest person in the film) is Channing’s Flo, whose character seems to have been suggested by Gypsy Rose Lee — although it’s worth adding that Avalon’s Angie, the youngest member of the mob, has a gaudy, high-tech bachelor pad (in the only scene shot on a Paramount soundstage), complete with Playmate pinups, bar, and circular rotating bed, that cross-references him with Hugh Hefner — an establishment figure whom some would locate on the other side of the film’s political divide. Yet this pad is also furnished, Fujiwara reports, “with transparent Plexiglass furniture similar to that in Preminger’s New York house.”(Groucho’s paranoid God, with a phobia for germs — sequestered on a yacht that Preminger rented from John Wayne, and outfitted with huge surveillance screens — is transparently based on Howard Hughes.)

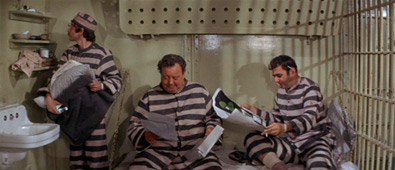

The “realistic” fantasy produced by all these unstable mixtures, combined with Preminger’s frequent tendency to cram as many people into his shots as he can, yields a vision of American democracy that’s complex, ambiguous, and in perpetual shifting motion (Preminger’s major theme), a form of confusion full of uncanny and/or intractable moments. When Tony finds Harry dead behind the wheel of Harry’s car inside Tony’s car wash — which is the mob’s way of compelling Tony to return to a life of crime and to kill “Blue Chips” Packard (Rooney), a privileged stockmarket tycoon in prison who’s a veritable doppelgänger for God, and is about to squeal to the feds — Preminger dutifully records Tony’s fleeting distress about the death of his pal, but then shows him brutally and indifferently shoving Harry’s corpse aside and onto the floor as soon as he climbs into the driving seat. (Much later, in prison, we see him burst into tears when he learns that Darlene is on God’s yacht — one of the many other Gleason moments in the film that are far from comic.) After a busload of body-painted hippies gets hauled into court, a gigantic yellow poster in the courtroom declaring, “BEAUTIFY AMERICA: get a haircut” is made to rhyme with Flo’s daffy yellow outfit when she turns up to claim Darlene, before inviting the entire hippie entourage to her house once Darlene refuses to part with her boyfriend Stash. Soon afterwards, in a touching detail, Flo can be seen shampooing various hippies at her kitchen sink. And not long after that, a seemingly gratuitous sequence shows prisoners, including Tony, filing from a paddy wagon into the toilet stalls of a dingy men’s room with peeling walls, en route to the prison, accompanied by a robust operatic aria sung by one of them, with full offscreen orchestral accompaniment on the soundtrack.

One of the film’s three pièces de résistance is Tony’s own lavishly and garishly illustrated acid trip, modeled after Preminger’s own, after accidentally ingesting LSD by licking an envelope flap in Fred’s stationary, which forces him to confront his sexual paranoia about Flo and Darlene and then destroys his willingness to kill anyone, including “Blue Chips”. The other two specialty sequences are the subsequent Garbage Can Ballet — an LSD vision of two tower guards played by Fred Clark and Nilsson, the latter of whom wrote the film’s songs, occurring while Fred and Tony are preparing to escape from prison in a homemade balloon — and the final credits, introduced offscreen by Preminger himself, which are sung in their entirety and may qualify as the film’s only unqualified comic success. But in fact, the whole film moves onto a higher level of expressiveness and giddy continuity once Tony takes acid and, in order to effect his and Fred’s prison escape, the entire prison population gets its food spiked with more LSD.

Fujiwara alerts us to the fact that the use of slow-motion in the resulting free-for-all in the prison kitchen culminates in a direct quote from Vigo’s Zéro de conduite (a source of inspiration that can be traced back to Cannon’s script, along with the no less radical channel-surfing at the film’s beginning). But this being a Preminger film full of sweet-and-sour Viennese flavors, there’s still plenty of sadness in all the overplayed comic hijinks. Fred Clark, in what may be his final screen performance as a babbling and tripping tower guard, is every bit as poignant in his vulnerability as Gleason.

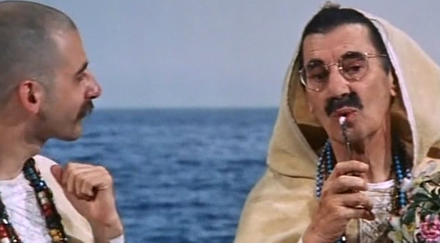

The ultimate ideological and emotional issue that divides the gangsters and their minions from the hippies is clearly sex, with women figuring throughout Skidoo as the prime aggressors (discounting the clumsy and failed seduction attempts of both Angie and God). When Flo, dressed as a pirate, leads the climactic hippie takeover of God’s yacht and belts out the film’s spastic title song, this is spelled out explicitly: “Skidoo, Skidoo, the only thing that matters is with who you do.” Soon afterwards, she resolves matters with Tony by going off in a cabin to have sex with him. But in some ways the movie’s true apotheosis, appearing in its final shot, shows Fred smoking dope with God in a sailboat, both of them dressed in Hare Krishna robes. (This is also Marx’s last screen performance — not a happy one, alas – as well as Pendleton’s first.)

Just before this, God’s compulsively unfaithful, seemingly nymphomaniac mistress (the model Luna) is seen getting married to Angie, with the ship’s skipper (Raft) officiating as Justice of the Peace with a book called The Death of God serving as his Bible. Immediately after the ceremony, she passionately kisses not the groom but Hechy (Romero) — which seems to suggest, no less ungrammatically than the title song, that “It really doesn’t matter with who you do.” In this respect, Fujiwara’s description of the film as “deeply contradictory” may be on the money after all. But it’s worth adding that the impossibility of coming away from Skidoo with any sense of certainty about anything also characterizes the features I regard as Preminger’s greatest and most successful ones — Laura, Angel Face, Anatomy of a Murder, and Such Good Friends — even though only the last of these rivals Skidoo in sheer grotesquerie. Whether graceful like the first three of these in black and white, or ungainly like the two in color, all five can be seen as both celebrations and indictments of Preminger’s swarming and perpetually unstable milieu, fascinated by their inscrutability.