Written for and published in Outsider Films on India, 1950-1990, edited by Shanay Jhaveri, Mumbai: The Shoestring Publisher, 2009 — a very handsomely produced book that I can highly recommend. — J.R.

The Creation of the World: Rossellini’s India Matri Buhmi

In my mind, there isn’t as much distinction between documentary and fiction as there is between a good movie and a bad one. — Abbas Kiarostami

From the beginning, film has owed an important part of its fascination to ambiguous overlaps between documentary and fiction —- sometimes experienced as conflicts between the separate aims of showing the world and telling a story, and frequently associated with incorporating both unforeseeable and carefully planned elements in a given film. It’s a tendency that can already be seen in the contrived gags of the Lumière brothers films, the re-enactment of recent famous events in some films of Georges Méliès, and the coexistence of fantasy and on-location actuality in Louis Feuillade serials. Later, of course, the same mix becomes re-animated in Italian neorealism and in work by French New Wave directors (perhaps most notably Jean-Luc Godard and Jacques Rivette and some of their immediate successors, such as Luc Moullet and Jean Eustache), in the improvisational strategies of Robert Altman, in some of the ambiguities found in the films of Abbas Kiarostami, Mohsen Makhmalbaf, and Jafar Panahi, and in practically all the films of Pedro Costa and Pere Portabella.

There are also certain ancillary tendencies within this odd encounter that can be found in a particularly interesting form — the fictional or fictionalized essay. Some noteworthy examples, all very different from one another, are Orson Welles’ F for Fake (1973), Edgardo Cozarinsky’s One Man’s War (1982), Gus van Sant and William S. Burroughs’ The Discipline of D.E. (1982), Leslie Thornton’s Adynata (1983), Françoise Romand’s Mix-Up (1985), Jane Campion’s Passionless Moments (1985), Joris Ivens and Marceline Loridan’s A Tale of the Wind (1988), Tony Gatlif’s Latcho drom (1993), and Mark Rappaport’s From the Journals of Jean Seberg (1995). And this personal list is far from being exhaustive; many other titles could be cited.

Clearly Roberto Rossellini is one of the key figures in the broader cutting-edge mode of crossing documentary with fiction, which came into prominence with Open City (1945) and Paisan (1946) and quickly expanded into other adventurous mixtures of reality and fantasy, such as the integral use of documentary footage of Naples within the fictional framework of Voyage in Italy (1953). So his India Matri Buhmi (1959), whose title means “India, Mother Earth” —- a French-Italian coproduction, and a sublime symbiosis of fable and non-fiction that poetically interrelates humans and animals, city and village, society and nature — comes at the end of a decade and a half of such experimentation. And it is also the supreme example in his work of the fictional-essay form.

Rossellini moved from human devastation in Italy and Germany at the war’s end to domestic issues raised by his adulterous liaison with Ingrid Bergman in such features as Europa 51 (1952) Voyage to Italy, and Fear (1954). The latter films flopped both critically and commercially, though for the young critics of Cahiers du Cinéma such as Godard and Rivette, they provided models of personal independent filmmaking that would eventually help to spark the French New Wave. Even the fact that Godard notoriously faked (that is, made up in its entirety) an interview with Rossellini about India Matri Buhmi that appeared — most likely coincidentally — on April Fool’s Day (1 April 1959) in the newspaper Arts, could be linked to his subsequent appropriation of related strategies in his filmmaking.

Such an impulse in Rossellini was at once theoretical and a practical consequence of his maverick reflexes as a filmmaker. One can find even traces of it in both his 1948 comic fantasy La macchina ammazzacattavi (“The Machine That Killed Bad People”), about a still camera that turns the people it photographs into statues (a fantasy that reflects on the documentary aspects of photography as viewed metaphorically) and in his direct-sound filming of a production of a stage oratorio (Paul Claudel and Arthur Honegger’s Jeanne d’Arc au bûcher) in 1954 with Bergman that was unprecedented in Italian filmmaking, where everything was dubbed.

From this standpoint, India can be regarded as the summation of Rossellini’s richest period — his crowning masterpiece that synthesizes many of the discoveries and investigations of his earlier masterpieces. Godard once even referred to it as “the creation of the world”, and the following remarks will attempt to provide a kind of gloss to that description. And whether the world in question can be described as the real one or as a fictional construct isn’t so much resolved by Rossellini as dissolved into a broader vision in which such questions become secondary. Above all, one might say that India — like many of the greatest films, an example of amateur filmmaking in the very best sense of that term (and one that proudly brandishes the fact that all its actors are nonprofessionals in its opening credits) — reinvents the world by virtue of reinventing cinema.

It’s remained one of the hardest to see of Rossellini’s major works, in part because of the complex and chaotic conditions under which it was made and initially received. For one thing, it was made concurrently with a ten-part television miniseries shot in 16-millimeter. (Produced jointly by RAI in Italy and ORTF in France, the latter was originally broadcast in both countries in 1959 under the respective titles L’India vista da Rossellini and J’ai fait un beau voyage par Roberto Rossellini.)

Furthermore, while working on the 35-millimeter feature, Rossellini, 51, became romantically attached to his main script collaborator, 27-year-old Sonali Sen Roy Das Gupta — a traditional Brahmin who was married and had two small children. (Ironically, she went to work for Rossellini only at her husband’s insistence, and after a great deal of hesitation.) The ensuing scandal forced both her and Rossellini to leave the country before the shooting was finished, leading to its eventual completion in French and Italian studios. (1)

During the period when Rossellini was editing India in Paris, he was also making periodic trips to Rome to edit his 16-millimeter TV documentary footage, meanwhile sending a couple of associates to India to shoot additional footage and flying off to Brazil himself for three weeks to pursue another film project that never materialized. After all this substantial and protracted (if sporadic) postproduction work, India Matri Buhmi eventually received its world premiere at the Cannes film festival in May 1959. The French producers were so unhappy with it that they refused to give it a commercial release, and the reception in Italy, where the film opened in a shorter version roughly a year after the Cannes premiere, was lukewarm at best. (2)

By common consensus, the French Cinémathèque’s only slightly faded 1994 restoration of the French version —- which survives in only one print, unsubtitled, and was even believed to have been lost for many years —- is the closest thing we have and probably will ever have to a definitive edition, and this is version that will be discussed below. This has never been available commercially, on film or on video, but it has been screened many times, in France and elsewhere. (3)

***

Divided, like Paisan, into separate stories with different characters and settings, but with a strictly documentary prologue and epilogue, India was originally supposed to have nine episodes, five of which were discarded. (It was also originally meant to be called India 57 —- dating it by year, like Rossellini’s 1947 Germany Year Zero and Europa 51 —- but the number got dropped after its release was delayed.) Like most of Rossellini’s greatest work, it conforms to what Godard once called “the definitive by chance”; it has the spontaneous, unpredictable feel of a jazz improvisation (or, to propose an analogy that would be closer to Rossellini’s own tradition, a bel canto performance) while remaining so simply and so lucidly focused that it becomes difficult to imagine it any other way. At once didactic and lyrical, it confirms that no matter how many theoretical suppositions Rossellini may have started out with, his creativity was at once intuitive and, based on the results, highly dialectical.

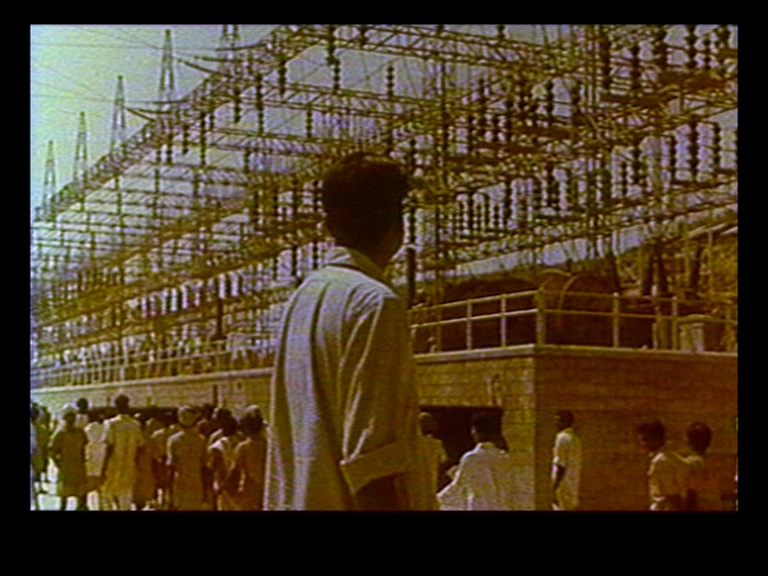

The four stories are linked and organized in remarkable ways, moving not only between non-fiction to fiction in each case, but also tracing a geographical survey of India and developing more broadly from youth to middle age to old age to death, meanwhile charting various transactions between humans and nature. Motifs that first appear in the early episodes (most strikingly, the birds, monkeys, and tiger that briefly appear in the first story) are developed in later ones. In all but the second episode, nature is represented by animals: elephants in the first, a tiger in the third, a monkey in the fourth. In the second episode, it’s represented by a man-made lake: a laborer is preparing to leave Hirakud with his wife and young son after five years of helping to build an enormous dam, as part of a crew of 35,000 workers.

***

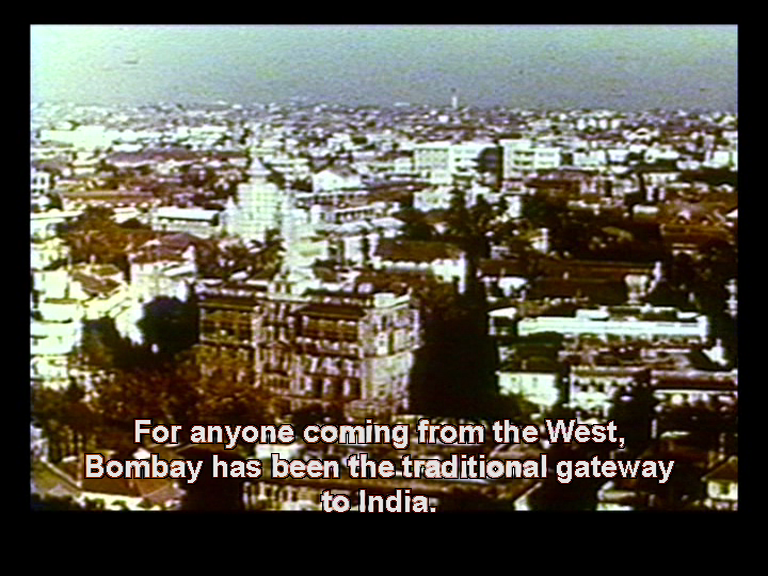

Deceptively, the documentary prologue seems conventional to a fault: scenic pans across cityscapes, a standard voice-of-God male narrator intoning what appears to be standard travelogue clichés in a commentary credited to Jean L’Hote, which begins, “For anyone coming from the West, Bombay has been the traditional gateway to India.” As we watch many shots of busy pedestrian traffic — most of them including camera movements that follow or discover various people via pans, zooms, or dollies that increase the overall swarming effect —- we hear a combination of lists and well-intentioned liberal platitudes, both of which are rather epic in scale, recalling the kind of hyperbolic, all-embracing catalogues that American writers such as Walt Whitman, John Dos Passos, and Jack Kerouac are famous for:

“On arrival one feels euphoria. The first

surprise is the crowds. One sees tens, hundreds,

thousands, tens of thousands, hundreds of

thousands, millions, forming an endless river

which has nevertheless not destroyed the vestiges

of the past that Moslems, Persians, and English

colonisers built.”

“Sun, shade and wind, droughts and monsoons,

have given a common appearance to these people of

diverse races and religions, peasants and others.”

[…]

“Innumerable languages buzz from the teeming

streets: Hindustani, Bengali, Assamit, Mazarati,

Tamil, Punjabi, etc.” [the list continues]…

“The blend of peaceful people and warriors

creates a peaceful place. These men with gold

turbans are Ismaelites, Moslem troops called

`Ashishin,’ the source of the word `assassin’,

now peaceful and hard-working.”

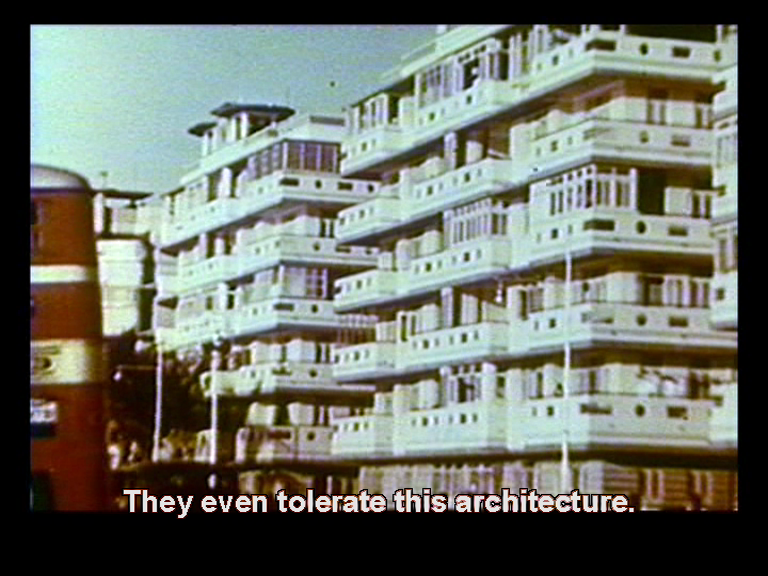

“The `promiscuity’ of heterogeneous elements

forms the Indian people, the most tolerant people

on earth. They even tolerate the architecture. Or

better yet…This tolerance suits them well for

any transformation or evolution, without their

ever severing their roots.”

“This crowd has fun like all the crowds in the

world: carousels spin toys, flutes, balloons,

windmills. This crowd relaxes and has fun, and

raises repair jobs to artisanal dignity. It carries

…transports…bears…etc. [the list continues]

It walks…ruminates…sleeps…dreams…rests. It

builds…works, using traditional or modern methods.”

“They’re a people whose traditions for thousands

of years have favoured peace over war, tolerance

over intolerance. A people who don’t want to convert

anyone.”

[A fadeout, followed by a shot moving past trees

and huts, ushers us into another sequence.]

“The most authentic Indians live in the 580,000 villages.”

“On only one-twentieth of the earth’s surface lives one-

sixth of the population. This dramatic reality is the

mode of modern India.”

***

The preceding transcription of Gallagher’s subtitles has been edited in spots. What it fails to convey is the restless and inventive style of the découpage, which periodically challenges whatever seems most commonplace about what one’s watching or hearing. One example is the somewhat unexpected way there are sudden shifts between generalities and specifics, whether these happen to be people (“these men with gold turbans”, who are specific, unlike the preceding generalities) or things (“the architecture”, a generality illustrated by a specific and persuasive onscreen example —- followed by a subsequent and no less ugly onscreen example that’s accompanied by, “Or better yet”).

In a comparable pattern of sudden shifts in the relation of commentary to image, one can also veer from semi-mindless patter (“This crowd relaxes and has fun”) to a non-sequitur (“and raises repair jobs to artisanal dignity”), just as one of the many images accompanying the extended catalogue of verbs (“walks… ruminates…sleeps… dreams”) shifts at the word “sleeps” from a man sleeping on the street to a sudden vertical pan from him up a statue behind him. And, one shot later, there’s a very slow matching pan down a tower just before the voice says, “It builds…” A pan up the tower would of course be the more conventional way of illustrating “builds”, just as a pan down to the sleeping man would be the more conventional way of illustrating “sleeps”; by reversing these apparent clichés, and also making a formal juxtaposition between them, something far more intricate than simple illustration is at work —- or at play, if one prefers.

What one finds in this opening sequence, in other words, passes periodically between a mode in which images are simply (or at least apparently) illustrating the commentary and a mode in which images take various swerves or detours away from the commentary, challenging or complicating the ostensible drift or meaning. And the commentary itself can occasionally become dialectical: if “the most authentic” Indians are indeed the villagers, whom we start to see in the second documentary segment, then the preceding urban Indians who have been presented to us as authentic have just had their authenticity undermined.

Eventually, in this second segment, we see an elephant, and the exposition again turns away from generalities to become specific: “The elephant has been brought to the city for a religious ceremony. It comes from the immense jungle, Karapur, where it works, lived wild, was captured and trained. The elephant is the bulldozer of India.” The next thing we know, we’re inside the jungle, and before we see an elephant again, there’s a casual exploration of the surroundings: the camera moves up a tree, then pans very slowly to the right while we hear the almost deafening sounds of birds and other creatures, some of which we subsequently see (monkeys, tigers) traversing the sky, trees, and ground, respectively. Gradually we’re introduced to a procession of elephants who clear away trees —- carrying some tree trunks with their tusks and hauling or dragging others with chains behind them while they’re guided in their work by mahuts (drivers).

We learn from the narrator that the elephants can only work three hours a day, from 7 to 10 in the morning, after which it becomes too hot, and the rest of the day is spent tending to them, which largely consists of bathing and feeding. This leads to a sequence of elephants being taken to a river and bathed and scrubbed by their mahuts that’s one of the most hypnotic, magical, and beautiful sequences in all of cinema, illustrating a kind of utopian interaction and harmony between men and animals that we are invited to savour in detail. By this time it’s become fully apparent that the narrator is one of the mahuts, who provides us with another epic list, this time regarding his own work: “For two or three hours you have to sprinkle them, wash them, scrub them, rub them, dab them, scrape them, rinse them, squeeze them, splash them, caress them, flatter them, reassure them, and uncrease them.”

An alert listener may note that the mahut’s narrating voice is not precisely the same one that spoke earlier about the pedestrians in Bombay. But the transition between the two voices has been so seamless that the shift of identities has clearly been indiscernible by design. (Logically, it isn’t the mahut who would be informing us authoritatively about “the most authentic Indians” or citing statistics relating to population and land mass, but these are in fact the first things we hear from the second voice.)

The remainder of this story recounts the mahut’s growing acquaintance with and courtship of a young woman he first glimpses at a puppet show that comes to the village, told in casual counterpoint with a respectful account of the mating habits of his elephants over the same period. (This sounds like the kind of parallel construction that could easily have smacked of glibness or cuteness, but the relaxed and graceful way it’s delivered precludes any such facileness.) After glimpsing the young woman several more times while feeding his elephants every day by cutting down leaves from tree branches, he gets a local schoolteacher to write his father a letter asking him to come to the village in order to propose marriage to the woman’s father, and the sequence concludes ten months after the wedding, by which time she and one of the elephants have both become pregnant.

***

Speaking at a conference held in Paris at the Louvre in June 15-16, 2001, critic Alain Bergala once suggested that Rossellini invented morphing in the French version of India — specifically in the transitional portions of the narration between the separate episodes. (4) Taken literally, this assertion would obviously have to be wrong, because morphing — the seamless digital transformation of one image into another image —- was first used extensively in a feature in 1988, on Willow. But Bergala clearly meant morphing as a concept and as a structure -— when one narrator or character imperceptibly merges into another and documentary morphs into fiction — which happens repeatedly throughout India, such as when the voice-of-God narrator of the prologue seemingly becomes the narrator and modest protagonist of the first episode. It’s a narrative method with a good many metaphysical and spiritual connotations, relating to reincarnation, to transubstantiation (in Rossellini’s own Catholic context), and to the metamorphosis of man into nature that occurs explicitly in the second episode, when the laborer/narrator, Tavi Chakravati, passes a corpse burning on a funeral pyre and reflects, “Maybe it’s beautiful to dissolve into nature”.

This episode, concerned with water, death, migration, and marital discord, is as melancholy as the first is jubilant. It’s almost as if the hopeful and happy young couple of the first episode has by now turned bitter and quarrelsome, their lives and livelihood having become somewhat more restless. Part of this is due to the sorrow and anger of Chakravati’s wife about having to leave their home — the site of a huge dam in Hirakud — five years after they were ousted from East Bengal because of the partition with Pakistan, now that he’s being moved to another job. (The dialogue, heard in direct sound, is untranslated, unlike the French narration.)

Here, I would surmise, Rossellini appears to be indulging in a certain amount of autobiographical self-projection, when the wife repeatedly berates her husband for condemning her to a loss of her home and domestic security. This impression is reinforced by the fact that Chakravati, as he wanders alone for most of this episode and ruminates philosophically on the soundtrack, is oddly made to seem a bit like a tourist himself, despite the fact that he’s worked on the dam for five years and takes pride in his work. Perhaps because he’s doubling here as a character and a commentator even more than the young mahut did, there’s a kind of documentary drift to the suspended narrative in this pensive segment that anticipates the work of Antonioni in the early 60s, even when the action and scenery turns most lyrical, as when he takes a ritual bath in the artificial lake.

The third episode is narrated by an 80-year-old man, happily married, who spends his days communing with his cows and the animals in the jungle near his home. His contemplative life is disturbed one day by the sounds of trucks prospecting for iron, causing most of the birds and animals to flee. With no other prey, a tiger attacks a porcupine, becomes wounded, and thus becomes dangerous to men for the first time, leading to a tiger hunt. But the old man, believing “the world is big enough for everyone,” has other priorities; preceding the hunters the next morning, he lights a fire that provokes the tiger into fleeing to safety.

The fourth episode, like the first, emphasizes the heat —- while the fire concluding the previous episode prepares us for it by comprising, as it were, a thematic “match cut”. But for once the narration, as in the prologue and epilogue, remains in the third person. An old beggar with a monkey, en route to a fair at Bagdel, collapses and dies from the heat, and his monkey, caught between the human and animal worlds, initially wards off vultures, and then travels alone to the city, where he continues to perform and collect money out of habit, not knowing what to do with the coins afterwards.

After the narrator recounts the monkey’s further adventures, which eventually bring him to a circus, the circus audience morphs into another street crowd that recalls the shots of Bombay at the beginning, and the narration morphs into the recitation of yet another catalogue — this one even more all-embracing, encompassing sheep, goats, cows, people, and even trees. The birds we finally see at the end evoke the vultures circling the beggar’s corpse, but like the tiger in the third episode, they’re simply part of the world —- no more and no less.

The narrative arc that has been described by the four stories —- depicting in turn young love and propagation, disillusionment and restlessness, a renewed love and serenity, and the isolation and sense of renewal that come with death —- also passes between men and animals while contemplating many different ways of both men and animals relating to one another as well as to the natural world. It’s part of the enduring strength of Rossellini’s masterpiece that he manages to tell one story and several stories at the same time, even while passing repeatedly between documentary and fiction —- and between a kind of visual prose and a kind of visual poetry.

Notes

1. See Under Her Spell: Roberto Rossellini in India by Dileep Padgaonkar (New Delhi: Penguin/Viking, 2008) for more details. According to Tag Gallagher’s The Adventures of Roberto Rossellini (New York, Da Capo Press, 1998), Sonali Das Gupta left India for the first time in her life in October 1957; two weeks ahead of Rossellini, she fled to Paris with her one-year-old son, where she wound up living in Henri Cartier-Bresson’s apartment; her presence in France remained a secret for some time, and late that year she gave birth to her and Rossellini’s daughter, Rafaella.

Rossellini, who was busy at the time having his already controversial marriage to Ingrid Bergman annulled, had a partially clandestine existence of his own — assisted in part by Henri Langlois and other staff members of the Cinémathèque Française, where Rossellini’s son Renzo was working at the time. (According to Fereydoun Hoveyda — another critic at Cahiers du Cinéma during this period, who hailed from Iran, and who preceded Das Gupta as a screenwriting collaborator on India — Langlois gave Rossellini a “small makeshift editing room” in the Cinémathèque’s premises. In program notes written for New York’s Anthology Film Archives in June 1998, Hoveyda also recalled that back in India, “as [Das Gupta] changed many of our previously [agreed-upon] stories, Rossellini used to call me [on] the telephone to discuss some points about the scripts.”)

2. Lamentably, the prints that have been circulated most widely around the world since then have been of the badly faded and dubious 1987 restoration of the Italian version — missing almost ten minutes, including most of the final sequence.

3. Recently, it was privately subtitled in English and on video by Tag Gallagher, and shown in public both in Los Angeles (at the UCLA Film Archives) and Chicago (through the auspices of the Chicago Cinema Forum); perhaps it has had other public venues as well. In Chicago, the two screenings held were so well attended that a third screening was added to accommodate the viewers who had been turned away. On that occasion (late August and early September, 2007), I published a short article about the film for the Chicago Reader that has been revised and expanded into this one.

4. The proceedings of this conference remain unpublished, although Bergala has written about Rossellini on several other occasions. My thanks to Nicole Brenez for telling me about Bergala’s remark, and to Bergala himself, for recalling to her some of the particulars.