From Film Quarterly (Spring 2009). — J.R.

One way of looking back at the sense of male privilege underlying much of the French New Wave would be to consider Céline and Julie Go Boating (1974) as a belated commentary on it. I’ve long regarded that masterpiece as a late-blooming, final flowering of the New Wave, especially for its referentiality in relation to cinephilia and film criticism. For one thing, it glories in the kind of compulsive doubling of shots and characters that François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Claude Chabrol, Eric Rohmer, and Jacques Rivette himself all discovered in Alfred Hitchcock’s movies. But it also puts a kind of stopper on the New Wave in the way it both underlines and responds to that movement’s sexism through the services of its four lead actresses, all of whom collaborated on its script: Juliet Berto, Dominique Labourier, Bulle Ogier, and Marie-France Pisier. Every male character, both in the story proper and in the film-with-in-the-film, is viewed as absurd, both as a romantic fop and as a narcissist who ultimately elicits the heroines’ scorn and ridicule: the patriarch (Barbet Schroeder) in the Phantom Ladies over Paris segments, playing his two phantom ladies (Ogier and Pisier) off against one another; and, in the story proper, Julie’s small-town suitor (Philippe Clévenot), Céline’s boss (Jean Douchet), and various male customers at the cabaret.

Some of that movie’s male fans could laugh at this ridicule and still be slow in recognizing its feminism. As an American expatriate in Paris and London who was friends at the time with Eduardo de Gregorio — the film’s only credited male screenwriter apart from Rivette — I could attend many early private screenings of the work print and could interview Rivette along with a couple of friends (Gilbert Adair and Lauren Sedofsky). But I could also write a series of dithyrambic pieces about the movie in the mid-1970s — in Sight and Sound, Film Comment, and London’s Time Out — without alluding once to feminism, as Robin Wood would point out in this magazine several years later (“Narrative Pleasure: Two Films of Jacques Rivette,” Film Quarterly, fall 1981).

I don’t think I was hostile to the feminist insights about male entitlement that would emerge with greater force by the 1980s, having already read Shulamith Firestone’s The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution (1970) more sympathetically than defensively in the early 1970s. But feminism had yet to become an everyday fixture in my arsenal of reference points, and the fact that I’d spent the first part of the 1970s in Paris certainly hadn’t helped matters much. I can still recall hearing about what may have been the first significant, well-publicized act of the French feminist movement of that era — in August 1970, during my first year abroad, only two years after the May 1968 uprisings — and even then the gesture had seemed pretty archaic: Christianne Rochefort, Monique Wittig, and others placing a wreath on the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier dedicated to “the unknown wife” of the Unknown Soldier.

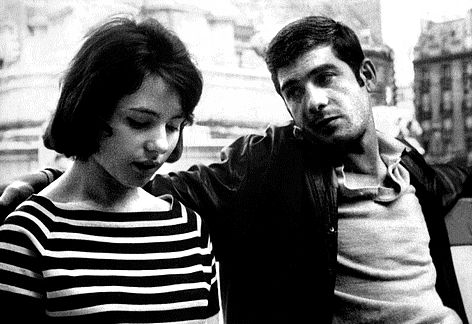

No less characteristically, I recall a quarrel I had with a French feminist many years later about the sexism of Rivette’s first feature, Paris Belongs to Us (1960). Though I could readily concede the misogyny lurking behind the rather artificial character of Terry Yordan (Françoise Prévost) — a noirish bitch goddess, clearly indebted (like much else in the film) to Robert Aldrich’s Kiss Me Deadly (1955) — I maintained that surely one felt a lot of empathy and even identification with Anne (played by Betty Schneider, who’d also appeared in Tati’s 1958 Mon oncle), the young Sorbonne dropout who’s the film central figure and is far more lifelike. I certainly knew that’s how I felt when I saw the film for the first time as an NYU freshman, at Cinema 16 circa 1961. To which my interlocutrice replied, indignantly, “Mais elle est moche!” (“But she’s ugly!”) — a startling indication of what she evidently considered necessary to both identification and respect. By these standards, it would appear that Emmanuèle Riva in Hiroshima, mon amour (1959), Jeanne Moreau in Jules and Jim (1962), and Corinne Marchand in Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962) all owed much of their status as feminist heroines to their credentials as glamorous fashion plates.

And what about A, the glamorous heroine played by Delphine Seyrig in Last Year at Marienbad (1961)? A broader part of the critique of Geneviève Sellier’s Masculine Singular: French New Wave Cinema, recently published in Kristin Ross’s English translation (Duke University Press, 2008), takes on the “masculinist” cult of the male protagonist (in this case, Giorgio Albertazzi) and auteur (Alain Robbe-Grillet) — with the former becoming the designated “alter ego” of the latter — that she associates with the New Wave, as well as the privileging of formal innovation over issues of representation. In both regards, Last Year at Marienbad takes on the status of a bad object, being described as “a film that gives an exorbitant privilege to the male protagonist by making him the narrator of a story whose interpretation he imposes at the expense of the female character” (11).

This characterization (not to mention the demonizing of auteurism) sounds more plausible if Robbe-Grillet’s screenplay is imposed at the expense of Alain Resnais’s direction. But plainly the film owes much of its power to the tug of war between writer and director as well as the struggle between Albertazzi’s X and Seyrig’s A. Sellier acknowledges that Robbe-Grillet even scripted a rape scene that Resnais refused to film, and T. Jefferson Kline has published a couple of fascinating studies that show Resnais subverting Robbe-Grillet’s screenplay and its gender bias in a number of ways, drawing particular attention to the insertion of a pointed reference to Henrik Ibsen’s Rosmersholm via a theater poster — a play involving both female emancipation and incest that Freud analyzed. (The fact that Resnais first encountered Seyrig in New York when she was acting in another Ibsen play, The Enemy of the People, is also deemed significant.)

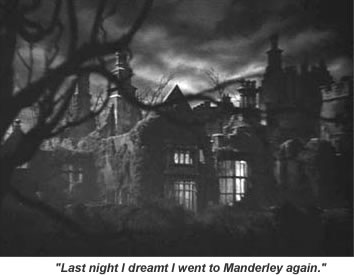

The first of Kline’s studies, cited by Sellier, is “Rebecca’s Bad Dream: Speculations on/in Resnais’s Marienbad,” a chapter in Kline’s Screening the Text: Intertextuality in New Wave French Cinema (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992); the second is Kline’s essay, “Last Year at Marienbad: High Modern and Postmodern,” included in the collection Masterpieces of Modernist Cinema, edited by Ted Perry (Indiana University Press, 2006). In the first of these essays, the Rebecca in question is Ibsen’s heroine, not Alfred Hitchcock’s — although Rebecca (1940), and in particular its trancelike opening sequence, could certainly be cited as one of Resnais’s key filmic sources. The second essay argues in fascinating detail that Resnais “would produce a film . . . that enacted a high modernist (consciously Freudian) reinterpretation of Alain Robbe-Grillet’s postmodern (unconsciously Lacanian) scenario” (209). And in a delirium of interpretation — a kind of activity that Last Year at Marienbad in particular seems to provoke — Kline begins his second essay by discussing Goethe’s “Marienbad Elegy” and Jacques Lacan’s attempt to present his paper on “The Mirror Stage” in Marienbad in 1936 before being silenced by Ernest Jones.

Given Resnais’s subtle subversion of Robbe-Grillet’s script as well as his insistence on treating Marguerite Duras as an equal creative partner on Hiroshima, mon amour, he clearly has more credibility from a feminist perspective than most of the other early male directors of the French New Wave. It’s worth adding that the recent French DVD of Hiroshima, mon amour, lamentably unavailable in North America, reprints letters, clippings, and photographs that were sent by Resnais in Hiroshima to Duras in Paris while he was scouting various locations for the film — which suggest that she may have never traveled to the title city herself and that the film’s extraordinary grasp of place, reflecting Resnais’s background as a documentary filmmaker, may have been entirely his own, even if he modestly (and characteristically) avoided taking any credit for it.

Part of the problem in figuring out the gender biases of the French New Wave and its audiences is differentiating boys’-club thinking in much of western culture during this period — for example, not just early features by Claude Chabrol and Jean-Luc Godard, but also such Beat manifestos as Kerouac’s On the Road — from specific French inflections and versions of that mindset. Take, for instance, the rather divisive ambiguity about male privilege and sexual double standards in Agnès Varda’s La Bonheur (1964), which shows a salt-of-the-earth carpenter (Jean-Claude Drouot) driving his faithful wife (Claire Drouot) to a probable suicide when he starts an affair with a postal worker (Marie-France Boyer), then marrying his lover to help raise his children while continuing to cultivate his kitschy happiness to the strains of Mozart. Varda herself has compared this film to a piece of fruit with a worm inside, but the late English critic Jill Forbes in The Cinema in France (Macmillan, 1992), among others, deemed it “unforgivable” — comparing its style to that of “soap powder advertisements” and ruling out the possibility of any ironic subterfuge on Varda’s part. A more general problem of identifying Varda too closely with her heroines — the title heroine (Marchand) of Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962), for instance— is sometimes matched by committing the same error regarding Godard’s identification with Michel Poiccard (Jean-Paul Belmondo) in Breathless (1959), or Chabrol’s with his own boorish heroes. Even if Godard himself would later call Breathless “a film that came out of fascism [and is] full of fascist overtones,” it would surely be oversimplifying matters to equate him simply with his gangster hero.

Sometimes the inflections are not merely French but 1960s French. Many commentators have persuasively argued that François Truffaut diminished the feminism of Henri-Pierre Roché’s novel Jules and Jim by combining most of its women characters into a single figure and ascribing many characteristics to that figure that were felt to be “eternally feminine.” It might also be maintained that some of the gendered aspects of the French language itself militate against certain feminist precepts. Consider the implicit confusions in the following passage from the novel (in Patrick Evans’s translation): “It was not long before Jules, as master of ceremonies, proposed that they abolish once and for all the formalities Monsieur and Mademoiselle and Madame by drinking to brotherhood, Brüderschaft trinken, in his favorite wine, and that to avoid the traditional and too obtrusive gesture of linking arms the drinkers should touch feet under the table — which they did.” And consider also the ideological confusions of 1960s counterculture that could embrace the bohemian “freedoms” of Truffaut’s characters without always examining everything they meant. As John Powers wrote in his liner notes to the Criterion DVD, “Sixties audiences didn’t merely see [François Truffaut’s] movie; they wanted to live it.” What living it might have consisted of is something we’re all still figuring out.