Some thoughts on Kon Ichikawa, from the June 3, 1988 issue of Chicago Reader. — J.R.

AN ACTOR’S REVENGE

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Kon Ichikawa

Written by Daisuke Ito, Teinosuke Kinugasa, and Natto Wada With Kazuo Hasegawa, Fujiko Yamamoto, Ayako Wakao, Ganjiro Nakamura, and Raizo Ichikawa.

ALONE ON THE PACIFIC (aka ALONE ACROSS THE PACIFIC)

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Kon Ichikawa

Written by Natto Wada

With Yujiro Ishihara, Kinuyo Tanaka, Masayuki Mori, Ruriko Asaoka, and Hajime Hana.

Scopophilia is a Freudian term that means the love of gazing, or pleasure in seeing. A punning use of the word often comes to mind when I consider the pleasures to be found in viewing ‘Scope movies. ‘Scope is movie buffs’ jargon for the anamorphic widescreen process known as CinemaScope (introduced by Twentieth Century-Fox in 1953 with The Robe) and a number of similar wide-screen formats; they dominated commercial filmmaking across much of the globe for well over a decade.

While a certain number of American movies today still make expressive use of this Band-Aid-shaped format — Shy People is an outstanding recent example — most directors consciously avoid it because they know that at least a third of the image will get lopped off when their work gets transferred to video. (Martin Scorsese: “I’ve been obsessed with ‘Scope for years, and would love to shoot everything in ‘Scope, but I realize that when it’s shown on TV, the power of the picture will be completely lost.”)

Ironically, ‘Scope was originally introduced by Fox as a response to the threat of TV. In a recent issue of Sight and Sound, critic John Belton theorizes that its shape was influenced by money in more ways than one — dollar bills have approximately the same ratio of width to height, 2.35 to 1 — so the final irony is that money, i.e., TV, later dictated the cropping of ‘Scope and therefore the avoidance of it as well.

In Japan they order these things somewhat differently. There ‘Scope movies have remained much more common, and video and laser-disc transfers traditionally preserve the original compositions by reducing them and including black areas at the top and bottom of the frame, a process known as letterboxing. In the U.S., only the most powerful directors have enough artistic control to get their ‘Scope films letterboxed — for example, Steven Spielberg’s The Color Purple, Woody Allen’s Manhattan. Infinitely better ‘Scope films such as A Star Is Born, East of Eden, and The Tarnished Angels are butchered mercilessly on TV; as others have pointed out, the damage done is far worse than colorizing.

It has been argued that ‘Scope works better in certain cultures and with certain subjects; Fritz Lang once noted grimly that it was best suited for snakes and funerals. The continuing popularity of and respect for ‘Scope in Japan undoubtedly has something to do with the importance of the horizontal line in Japanese architecture and its diverse ramifications, such as the fact that at home the Japanese mainly live on the floor. I have often traced much of my own love for the ‘Scope frame — my scopophilia, as it were — back to the fact that I was fortunate enough to have grown up in a Frank Lloyd Wright house in Alabama that is very horizontal and Japanese-influenced. In the same connection, it is worth noting that the most accomplished ‘Scope director in Hollywood during the 50s was Nicholas Ray, a former student of Wright who often spoke about this “horizontal” influence.

The two films under review, showing this week and next at the Film Center, were both made by the very versatile Kon Ichikawa in 1963. As utterly different as they are from each other, they have three striking traits in common. Both deal with the obsessive carrying out of a personal project by a lone individual; both are structured around a series of flashbacks that clarify the heroes’ present quests by placing them in a familial context; and both use ‘Scope so brilliantly and integrally that it is impossible to imagine either film existing — much less succeeding — without it. (The films also share a writer — Ichikawa’s wife, Natto Wada, who worked on his films from 1948 to 1965, when she retired from screenwriting — although neither is based on original material.)

A remake of Teinosuke Kinugasa’s 1938 film of the same title, An Actor’s Revenge is the 300th film of matinee idol Kazuo Hasegawa, who plays a double role as a thief and an onnagata (female impersonator) Kabuki actor — the same two parts he played in the original Kinugasa film. The elaborate story concerns the actor’s efforts to get even with a number of individuals who drove his parents to suicide when he was a child. None of his intended victims knows his present whereabouts or identity. (The Japanese title is Yukinojo henge, which translates as The Ghost of Yukinojo.) As in many Elizabethan and Jacobean revenge plots, a simple slaying of his enemies isn’t all that the hero is after; because his father was driven mad before he hung himself, Yukinojo wants to torture his own victims until they go mad themselves.

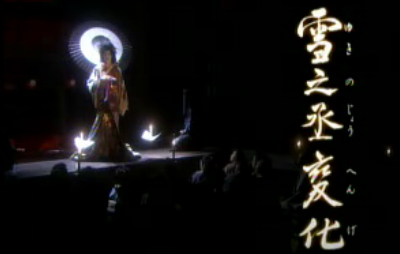

This supposedly traditional and macho theme is given a bizarre twist at the outset by the fact that Yukinojo, an excellent swordsman, remains in drag and maintains the feminine persona and mannerisms of an onnagata throughout the film, onstage and off. And his profession as a Kabuki actor counts for a good deal more than background detail. While the film opens and closes with one of his onstage Kabuki performances — both of them attended by Yamitaro, the pickpocket who figures as Yukinojo’s male doppelganger — the remainder of the film runs the gamut from naturalism to Kabuki stylization, guaranteeing that nothing is ever quite what it seems initially.

Consequently, thanks to Ichikawa’s endlessly inventive and brilliantly playful mise en scène, one is never sure precisely where one is (onstage or off) or how one is supposed to take a given scene: as camp, as tragedy, as farce, as romance, as black comedy, as melodrama, or as action thriller. At various points, each of these modes becomes dominant before subtly transforming itself into another. And the film’s overall sense of space — not to mention its overall sense of reality — is comparably elastic.

The musical score, for example, often oscillates between syrupy romantic strings and contemporary mainstream jazz; while this approach certainly has some precedents — Martial Solal’s lovely, unheralded score for Godard’s Breathless is structured around a similar pattern of alternations — its incongruous use in a Japanese period context makes it a good deal weirder. The parameters of lighting, to cite another example, are comparably unfixed; naturalistic lighting in a conventional interior scene might suddenly veer, in the middle of a shot, to a spotlight on Yukinojo surrounded by darkness. Elsewhere, as Noël Burch has pointed out, “a thick yellow fog gradually dissolves to reveal a painted representation of fog on a canvas backdrop.”

It is important to realize that this deliberately perverse presentation represents an aberration in Japanese culture as well as in our own. The film was a box-office flop in Japan when it came out, and Japanese critics continue to regard it as a potboiler; and while U.S. film buffs have widely recognized it as one of the great Japanese movies over the past quarter century, surprisingly little has been written about it. Like Kinugasa’s dazzling silent and expressionist A Page of Madness (1926), which it resembles in no other respect, An Actor’s Revenge cannot easily be absorbed into surveys of Japanese film because it stands defiantly apart from most recognized traditions.

Ichikawa’s breathtaking use of ‘Scope becomes central to his conception because of the horizontal sweep of the Kabuki stage, which serves as a kind of baseline on which he builds his inventions. (The effect is later duplicated by a long, low fence or wall, a foundation for much of the “exterior” action.) This broad canvas allows the director a variety of interesting effects: he can mask the screen to delimit certain areas of action or even alter the shape of the picture; he can employ trick shots that allow Hasegawa’s two characters, the actor and the thief, to converse within the same frame; and, in moments of swordplay and other quick action, he can cut suddenly from extended takes in long shot to short, staccato bursts of action in close-up without missing a beat. (Most Hollywood ‘Scope films, apart from Samuel Fuller’s, tend to avoid quick cutting, on the theory that it takes a viewer longer to “read” a wide-screen image; Ichikawa’s refusal to follow this princlple — or, rather, his personal alteration of it to suit his own ends — is often refreshing.)

Ichikawa shows what he’s up to right from the opening sequence, in which we see Yukinojo performing onstage (his drag mannerisms suggesting a somewhat more slender and fastidious version of Divine) in a stylized setting of artificial failing snow, with the entire width of the stage visible from a distance — a black and white expanse that prepares one for some of the gorgeous color effects to follow. After an oval-shaped insert appears over this image in the upper right of the screen, containing various explanatory flashbacks, there is a cut to Yukinojo onstage in close-up, and the falling snow around him is suddenly made to appear real — in effect turning a stage setting into a natural exterior before we return to the long view, where the snow seems artificial again.

All things considered, the kind of stylistic freedom discovered by Ichikawa in An Actor’s Revenge is comparable to the exhilaration found in certain Hollywood musicals — although if an American counterpart is sought, perhaps the nearest equivalent would be George Cukor’s Sylvia Scarlett (1935), featuring Katharine Hepburn in drag, with its own uninhibited confusions of genders and genres.

Perhaps the closest American equivalent to Ichikawa’s other 1963 film, Alone on the Pacific, is Billy Wilder’s The Spirit of St. Louis (1957) — a lengthy account of Charles Lindbergh’s nonstop solo flight across the Atlantic in 1927, based on Lindbergh’s book. Spirit also happens to be in ‘Scope, but it’s their subjects, not their styles, that make the two films comparable. Stylistically, Wilder’s film serves mainly as a measure of just how unconventional even a relatively “conventional” Ichikawa film can be.

Alone on the Pacific is based on a true account by Kenichi Horie, a young Japanese who sailed alone from Osaka to San Francisco in a 19-foot yacht over 94 days in 1962. Made the following year, using Horie’s log as its principal source, the film was apparently a commercial success in Japan , and showed at the New York Film Festival in 1964, but it has not been very visible in the U.S. since then. Last September, Penelope Houston, the editor of Sight and Sound, selected it as part of a series called “Buried Treasures” at the Toronto Festival of Festivals, and that led to its becoming available again in North America.

A film about solitude and solitary obsession, this adventure story is less obviously suited for ‘Scope than An Actor’s Revenge, if only because the shape and length of Horie’s boat, the Mermaid, is not really equivalent to a Kabuki stage. But the expanse of the Pacific, and the isolation of the hero and his boat in relation to it, has much more graphic impact in a wide-screen format. And, no less important, Ichikawa’s unconventional uses of ‘Scope — both on the boat and in flashbacks to the hero’s conflict with his family on the mainland — make it an essential part of the story he has to tell.

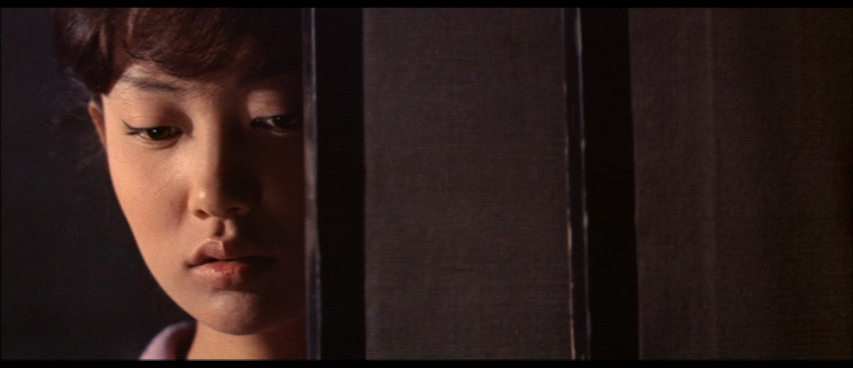

Why does Horie (Yujiro Ishihara) insist on making the trip, even after his father (Masayuki Mori) threatens to disown him for giving up his education to pull such a stunt? The closest thing we get to an explanation occurs during one of the later flashbacks, at a family meal shortly before Horie leaves, when his mother objects to his plan. (One should note in passing that Kinuyo Tanaka, who plays the mother, is a major figure in the Japanese cinema — not only a leading actress in films by Mizoguchi, Ozu, and Kurosawa, but also the first Japanese woman to become a film director.) After Horie admits that he might get arrested upon arriving in the U.S., for traveling without a passport, he remarks that foreigners have previously done what he is about to do, but no Japanese. “It’s a disgrace,” he says. “We’re a seafaring nation!”

This remark gives Horie’s journey something of a context (and its patriotic note suggests a further parallel with Lindbergh), but its placement late in the film makes it something less than an explanation; it certainly isn’t made to seem the theme or subject. As Ichikawa depicts the voyage, it is closer to an existential test — a gratuitous act played out against a void. And the combination of ‘Scope and the Pacific helps to articulate that void.

Much as high-fidelity sound reproduction intensifies a record’s scratches as well as its musical nuances, ‘Scope encourages directors to make their compositions either less or more interesting than they would be otherwise. The dull center framing of early ‘Scope films like The Robe encourages the eye to wander, but without the assurance of finding anything more to look at when it does. Ichikawa, by contrast, regards the elongated screen as a graphic challenge to subdivide space meaningfully — which, in the case of Alone on the Pacific, often means giving it an out-of-kilter quality that reflects the imbalances and conflicts in the protagonist’s mind. (Similar effects are achieved in the editing and the musical score; the latter, as in An Actor’s Revenge, combines jazz with more Hollywoodish “mood” music, although the juxtapositions are much less radical.)

Eccentric camera angles are used in the flashbacks, serving mainly to highlight the hero’s distance from his family (as well as, on occasion, from us); one shot that places him and his sister (Ruriko Asaoka) at opposite ends of the frame strikingly anticipates a scene in the current Shy People, a shot that expresses the estrangement of a mother (Jill Clayburgh) and daughter (Martha Plimpton) in a New York apartment. Elsewhere, Ichikawa uses ‘Scope for phantasmagoria (Horie hallucinating a conversation with his own transparent ghost, or imagining in his solitude various things he might do); for the hero’s alienated encounters with a passing plane and ship; and for a variety of spectacular effects, ranging from a shot taken from the top of Golden Gate Bridge to a screen-filling shot of dirty water emptying from a bathtub — an uncanny afterimage of the Pacific.

It’s a measure of Ichikawa’s talent that he can turn even a sequence about stocking the boat’s supplies into a visual poem that includes, thanks to ‘Scope, both text and illustrations. At screen left, the camera moves down a list of necessities, creating the effect of a moving scroll; at screen right, we see shots of various preparations being made. Whether filling up the screen or emptying it out, Ichikawa rewards our scopophilia with a string of enchantments.