This is my 31st “En movimiento” column for Caiman Cuadernos de Cine, formerly known as the Spanish Cahiers du Cinéma, written in late March, 2013.

For other thoughts of mine about Resnais, here are a few links:

http://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/2012/03/on-alain-resnais/

http://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/2009/11/the-unknown-statue-tk/

http://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/2009/09/17072/

http://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/2007/06/two-key-scenes-from-alain-resnais-films/

http://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/2005/03/the-past-recaptured/

http://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/2000/03/20108/

http://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/1988/04/alain-resnais-and-melo/

— J.R.

After recently having caught up with Alain Resnais’ magisterial Vous n’avez encore rien vu, I belatedly discovered from diverse sources on the Internet that “Axel Reval,” the credited cowriter on both this film and Les herbes folles, is in fact a Resnais pseudonym, making it a typically sly acknowledgment of the personal nature of his filmmaking, which has been an essential part of his work since the 1950s. Remember the glimpse of the Mandrake the Magician comic strip found in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Toute la mémoire du monde? One could even argue that the fact that personal moments of this kind tend to be veiled or masked in Resnais only makes them more intense, as they sometimes are in the films of Sternberg. (Claude Ollier’s alternate title for The Saga of Anatahan: My Heart Laid Bare.)

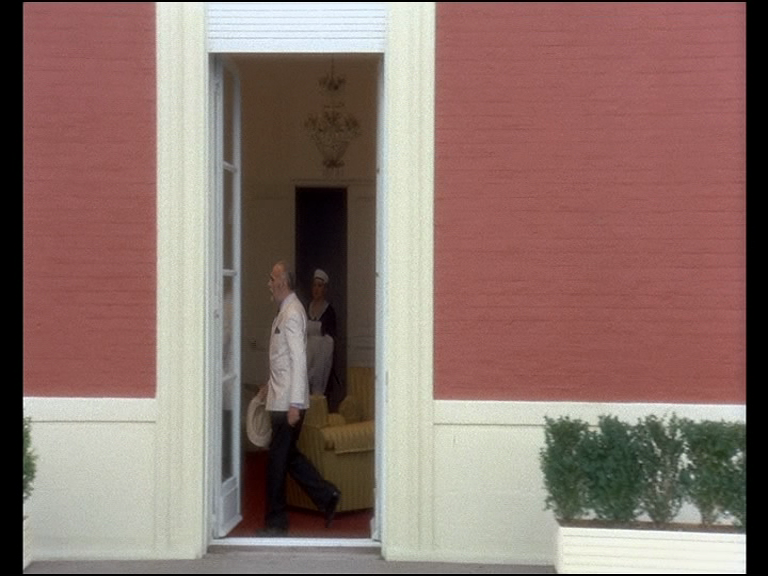

Indeed, it might make an interesting exercise to run through Resnais’ oeuvre picking out such intense but half-hidden and fleeting details spelling out his personal investments in the films. An obvious example, in L’année dernière à Marienbad, is the life-size blowup of a photograph of Alfred Hitchcock, eavesdropping on hotel guests beside an elevator, shortly before X makes his first on-screen appearance. And less obvious, because much harder to locate, is the comparable Hitchcock cameo in Muriel: this time he’s glimpsed on the street, in front of a restaurant, wearing a chef’s hat. And if we add to this the crane shot around the exterior of a luxury hotel in Biarritz in `, past the various windows of the opulent suite of Arlette (Anny Duperet) when Baron Raoul (Charles Boyer) is paying her a visit — Resnais’ quintessential Lubitsch reference — we’re talking mainly about the personal nature of Resnais’ cinephilia, which, at least in this latter example, also proves that he’s something of a film critic, working with sound and image rather than prose, much as Godard does in portions of Alphaville and Made in USA.

Yet in fact, what’s most personal in this ravishing sequence isn’t the Lubitsch reference but what Resnais subsequently does with it and to it — a sudden shock cut from the Baron knocking on Arlette’s bedroom to a close-up of her turning her head with a startled expression — for me, one of the most beautiful and frightening cuts in the history of cinema, and one encapsulating the entire film by turning Stavisky’s dream of glamor into something like a nightmare. Or think about the apparently gratuitous crane shot over the hero’s house in Les herbes folles, up one side and then across the roof and down the other side, providing a kind of stylistic explosion that’s no less breathtaking but, for me at least, much harder to analyze in thematic terms. But as one character puts it in Providence — clearly speaking for Resnais, even if he’s hiding in this case behind David Mercer’s dialogue — the charge that style overrules feeling rules out the salient possibility that style is feeling.

One of the most personal moments in Vous n’avez encore rien vu — perhaps the most personal of all, occurring after a veritable string of coups de théâtre combined with diverse contradictory and paradoxical reflections about death — is the Frank Sinatra song heard over the final credits, “It Was a Very Good Year,” beginning with the line, “When I was 17…” Even though Resnais was in fact 19 when Anouilh’s Eurydice opened in Paris, during the second year of the German Occupation — a play that, at least in Resnais’ version of it, exudes the darkness, the cellar-like dinginess, and the paranoid taste of betrayals that one associates with that time and place, even more than Cocteau’s Orphée would remember it a few years later — the bitter irony of those lyrics encapsulates the sweet (and yes, personal) anguish of everything preceding them.