Written in January 2006 for 1000 Films To Change Your Life, an anthology edited by Simon Cropper for Time Out. — J.R.

Wonder is closer to being a feeling than a thought, and one that we associate both with children and with grown-ups recapturing some of the open-mouthed awe and innocence that they had as children. Many of us experienced some of this as kids watching the classic Disney cartoon features or certain live-action fantasy adventures like King Kong (1933) or Thief of Bagdad (1940).

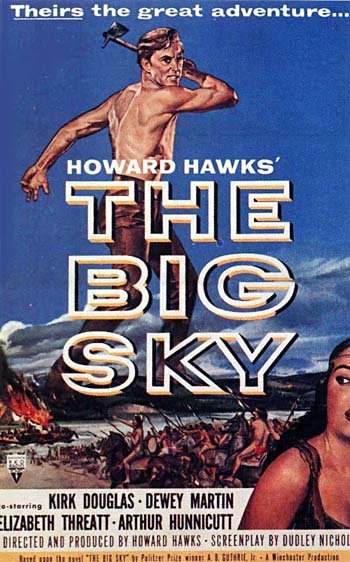

Other generations, for that matter, might recall feeling a comparable emotion before the vast spaces of the 1916 Intolerance (whose gigantic Babylon set would eventually be redressed for Kong’s Skull Island) or the 1924 Thief of Bagdad or the 2005 King Kong —- or even in that hokey opening line, “A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away…” Or what about the hushed sense of reverence that we bring to the virgin wilderness of The Big Sky (1952), whose very title expresses our feeling of astonishment? It’s a primal emotion, particularly as it relates to cinema in the old-fashioned sense: 35-millimeter projection in palatial theaters, the screen invariably much larger than us (‘Bigger Than Life,’ as the title of a Nicholas Ray melodrama in CinemaScope has it). Of course, with the advent of digital video, smaller screens, home viewing, and a more detailed interest on the part of the public in understanding how various visual effects are achieved, some of this innocence and involvement has been altered. But our primal sense of wonder tied to the cinematic experience remains, in spite of everything, and without it I’m not even sure if we’d still be watching nearly as much.

If we consider the role played by our imaginations in ‘completing’ a film’s image and sound —- filling in the dark spaces that appear between the film frames without ever consciously seeing them; and doing pretty much the same thing with offscreen spaces, such as responding creatively to suggestive soundtracks by filling in additional images of our own —- this shouldn’t be at all surprising. ‘I want to give the audience a hint of a scene,’ Orson Welles said early in his career. ‘No more than that. Give them too much and they won’t contribute anything themselves. Give them just a suggestion and you get them working with you.’ In fact, he was referring explicitly to theatre and implicitly to radio when he said this in 1938, not to cinema at all. But the sense of wonder he brought to movies soon afterwards in Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons had a lot to do with adapting some of the discoveries he’d already made about other dramatic forms to express a certain wonderment about America in the late 19th century. One might even add to this that the medium for expressing this wonderment is secondary; it’s the feeling itself that remains primary —- the experience of remaining an infant basking in the warmth and expanse of a maternal screen and wondering where all this bounty comes from.

The recent military term ‘shock and awe’ could be viewed as a kind of perversion of cinematic wonder, sought after and applied with the aggressive assault of a blunt instrument. There’s always been this brutal side to movies as well, though I think it would be lamentable to associate this kind of coercion too closely with wonder. The best kinds of wonder in movies are the ones that invite and encourage idle speculation rather than those that are designed to settle disputes, stop conversations cold, or simply intimidate. Wonder is a kind of question mark from which fear is not so much abolished as held in an exquisitely sustained abeyance, allowing the mind in a relaxed state to fill in the gaps with all sorts of possibilities. Terrifying and brutalizing the spectator, by contrast, has zip to do with soliciting the gentler responses of wonder.

Charles Laughton’s sublime The Night of the Hunter (1955), charting the nightmarish pursuit of two children by an insane and deadly preacher (Robert Mitchum) across an Expressionist version of rural Depression America, certainly has its chilling moments. Yet these are mainly experienced as secondary to the sense of poetic wonder felt by these children about the world they’re inhabiting and sometimes rushing through. There’s a sinister edge to the preacher’s nocturnal silhouette on horseback as seen by the boy protagonist from a distant hayloft while he hears the villain faintly singing ‘Leaning on the Everlasting Arms’. Yet it’s the boy’s relatively calm sense of wonder about this threat —- ‘Don’t he never sleep?’ —-that leaves the most profound impression. If fear were all he was experiencing, we wouldn’t wind up with any sense of wonder at all.

Another emotion that needs to be sharply distinguished from wonder is curiosity — especially the kind that killed the cat and that leads us remorselessly through whodunits. Let’s call curiosity in this case a very limited kind of wonder, restricted mainly to details of plot and character that fill out an incomplete jigsaw puzzle. Wonder is more spiritual and all encompassing than that, and therefore less geared as a rule to straight-ahead storytelling. As gifted a storyteller as Steven Spielberg is, the moment in Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) when we arrive at the massive landing of the huge alien spaceship is basically a stretched-out moment when the story stops and the spectacle takes over. I’m reminded of the term used by the American film theorist Tom Gunning, “the cinema of attractions,” that links early movies to carnival sideshows rather than serial cliffhangers. Both are of course essential aspects of our experiences of movies, but the elements that provoke our wonder are more apt to exist as spectacle than as plot or action: the landscapes in an Anthony Mann western like The Naked Spur (1953) or Man of the West (1958) or the fairy-tale waterfall in Nicholas Ray’s Johnny Guitar (1954).

And when we turn to independent cinema and art cinema, a sense that people and life are ultimately unknowable — or at least unfathomable — lies behind the sense of wonder about the world and the human condition conveyed in very different ways by Michelangelo Antonioni, Robert Bresson, John Cassavetes, Carl Dreyer, and Atom Egoyan (to restrict my list to just the first five letters of the alphabet).

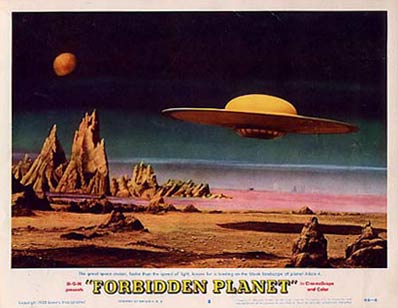

The late science fiction writer Damon Knight titled his excellent collection of science fiction criticism In Search of Wonder, and it’s certainly true that it’s a sense of quiet amazement and bemusement that draws us to both SF and fantasy, either on the page or on the screen. It’s the main thing we bring away from outer-space yarns as disparate as Forbidden Planet (1956) and 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), and stories about androids and future cityscapes as different from one another as Metropolis (1927), Blade Runner (1982), and A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001). On the other hand, wonder isn’t at all what we bring away from SF satires like Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964) and A Clockwork Orange (1971), or Paul Verhoeven’s RoboCop (1987) and Starship Troopers (1997), because sarcasm and wonder rarely make compatible bedfellows.

The sense of immensity and monumentality conveyed in SF films such as Things to Come (1936) isn’t necessarily just a function of the way we feel about the future. There’s another string of films conveying a similar sense of bottomless mystery about the historical past, ranging from Howard Hawks’ 1955 bombastic and campy but awestruck spectacular Land of the Pharoahs to Kubrick’s more muted and melancholy 1975 Barry Lyndon (a kind of variant of Welles’s aforementioned Ambersons) —- or from the exquisite Hong Kong biopic Actress (1992), (with Maggie Cheung as Ruan Ling-yu, the Chinese Garbo, working in the Shanghai film industry of the 30s), to Richard Linklater’s underrated saga about a Texas family of 1920s bank robbers, The Newton Boys (1998).

Some filmmakers such as Alain Resnais and Andrei Tarkovsky take us on guided tours of metaphysical worlds, mysterious and uncharted labyrinths of the mind. I’d call them quintessential directors of wonder, above all because their appeal remains sensual and emotional rather than intellectual while plumbing the depths of our inner lives, the kinds of secrets and hidden desires we sometimes keep even from ourselves. If you misread Resnais and Alain Robbe-Grillet’s Last Year at Marienbad (1960) or Resnais and David Mercer’s Providence (1977) as intellectual or cerebral puzzles, you aren’t likely to catch their poetic handling of nocturnal moods and the imaginative, dreamlike drifts that course through both of them like uncanny, subterranean tunnels.

There’s another sense of the uncanny found in Tarkovsky’s Solaris (1972) and Stalker (1979), both deceptively derived from SF novels of ideas. I would argue that both films have relatively little to do with these ideas — and quite a lot to do with the gut feelings and intuitions of someone experiencing both spiritual desolation and a feeling of awe about the universe he inhabits.

Apart from the church hymn sung by Mitchum, I haven’t yet said anything about music. Yet this clearly plays a substantial role in establishing our gaping sense of wonder in many of the above examples — the “Blue Danube Waltz” of Strauss in 2001: A Space Odyssey and the eerie organ music resembling a spooky silent film accompaniment in Last Year at Marienbad; the romantically lush, Hollywoodish Miklos Rosza score in Providence and the ecstatic burst of the choral climax of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony in the final sequence of Stalker.

Which makes it only logical that some of the ultimate expressions of amazement in movies come to us courtesy of actual musicals. Consider the awe-inspiring geometric shapes of chorus girls in Busby Berkeley production numbers, the astonishingly gaudy spectacle of Marilyn Monroe and Jane Russell in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953), or even something as relatively modest as Donald O’Connor dancing wildly around a park pavilion in roller skates in I Love Melvin the same year. For the truth is we can only gape at such soulful visions of glitz, grace, and synchronicity, making us gullible kids all over again.

JR’s Score of Movie Wonders

Tih Minh (1918). My favorite of the wonderful Louis Feuillade serials of the teens —- all of which feature masked criminals, intricate schemes and subterfuges, resourceful servants, dopey lounge lizards, lovely natural locations (such as the Paris settings in Les Vampires or the Côte d’Azur settings here), jaw dropping stunts, and a perpetual sense of fantasy rubbing shoulders with documentary actuality.

Foolish Wives (1922). Erich von Stroheim had never even been to Monte Carlo when he decided to rebuild it on the Pacific Coast in all its glory and play a master Russian swindler and seducer inside this gargantuan set. He robs unsuspecting American tourists blind, especially the ladies in his title, and the so-called Man You Love to Hate can’t help but command our guarded respect for doing so.

Blonde Crazy (1931). Cut to some low-grade urban hijinks in the thick of the Depression, when James Cagney and Joan Blondell perform their own sassy scams with and against one another and sometimes get burned by still others. We can only admire the energy of everyone’s con-artistry.

Ivan (1932). Meanwhile, over in Russia, they’re idealistically building huge dams like the one in Alexander Dovzhenko’s first talkie. But the fact that we never even see this one completed is part of the goofy conceit of this poetic fable, which shows more affection for a crusty old peasant who refuses to move a muscle than for all the laborers breaking their backs.

Sylvia Scarlett (1935). A highly subversive bending of both gender and genre that tanked at the box office because audiences didn’t know what to make of it. Katherine Hepburn disguises herself as a boy, and when Cary Grant (in a rare part exposing his Cockney origins) gets the hots for him (or is it her?), we aren’t sure whether to laugh or cry. Director George Cukor keeps everybody on his or her toes, including us.

Ivan the Terrible, Parts I and II (1944-46). Sergei Eisenstein’s underrated masterwork is at once a period saga, the greatest Flash Gordon movie ever made, a devastating portrait of Josef Stalin’s paranoia, a critical self-portrait with psychoanalytical overtones, and a Gothic nightmare of angularity. And to make matters worse (or better), the whole thing seems to be experienced through the eyes of a ten-year-old.

The Three Caballeros (1945). The Disney studio at its most avant-garde mixes South American live-action and giddy animation with such abandon, and in so many riotous colors that explode into so many alternate and abstract counter-realities, that Busby Berkeley must have been eating his heart out. Donald Duck ogles senoritas and the universe expands.

Park Row (1952). The great Samuel Fuller couldn’t convince Fox to bankroll his action-packed hymn to the birth of New York yellow journalism —- Darryl F. Zanuck suggested he do it as a musical —- so he sank his own money into this vest-pocket Citizen Kane, filmed on a cozy period set, and lost every penny. Hyperbolically sincere and reverent about things like the invention of linotype and a statue of Benjamin Franklin (against which Gene Evans’ editor-hero bashes out a villain’s brains).

The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T. (1953). The weird imaginings of children’s author Dr. Seuss expanded into a Surrealist nightmare with musical numbers about a diabolical piano teacher (Hans Conreid) who imports 500 hapless kids to his castle to play his favorite exercise on a continuous keyboard. Perhaps I found this tacky monstrosity unforgettable at the age of ten because I was the same age as the hero (Tommy Rettig).

Ordet (1955). What better illustration of stupefied wonder than a genuine miracle? Reportedly Carl Dreyer wasn’t even religious, yet he made this heavy, rural chamber piece about family discord and faith into a challenging confrontation for believers and nonbelievers alike.

The Tiger of Eschnapur and The Indian Tomb (1959). Fritz Lang’s return to European filmmaking after a long sojourn in the U.S. was a big-budget remake of a fantasy that he’d originally cowritten with his wife Thea von Harbou in the early 20s. This opulent fairy tale in colour was popular with the public, at least in Europe, but its deliberate childlike innocence alienated most critics, who should have known better.

Shadows of Our Forgotten Ancestors (1964). The first feature of the visionary Armenian-born Soviet filmmaker Sergei Paradjanov to reach the west, adapted from a Ukrainian novel and set in the Carpathian Mountains. This delirious merging of myth, folklore, history, poetry, ethnography, dance, and ritual begins with the cutting down of a majestic tree in a forest, which is partially seen from the viewpoint of the toppling tree.

Playtime (1967). To realize his greatest film, Jacques Tati built an entire city on the outskirts of Paris and turned his own most famous character, Monsieur Hulot, into one of many extras, insisting democratically that ‘the comic effect belongs to everyone’. Perhaps the cinema’s greatest illustration of community triumphing over architecture.

Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972). An opening title of this pie-eyed epic about a mad Conquistador (Klaus Kinski) in search of El Dorado through awesome natural landscapes claims that this has some historical basis, but filmmaker Werner Herzog freely admitted that he made the whole thing up — and put together a mad expedition of his own in order to film it. One doubts that Apocalypse Now (1979) would ever have been conceived without its shining example.

Celine and Julie Go Boating (1974). Jacques Rivette’s deliciously fusing of Lewis Carroll with Vincente Minnelli (as updated by Jean Rouch) into an uncanny horror comedy. It was cowritten by the four lead actress —- Juliet Berto and Dominique Labourier as the goofy title heroines in Paris, Bulle Ogier and Marie-France Pisier as the phantom ladies in an old dark house in the suburbs that the other two periodically visit—- in collaboration with the Argentinian magical realist Eduardo de Gregorio, and over its 193 minutes, wonders never cease.

Perceval le gallois (1979). Eric Rohmer’s overlooked musical, based on Chretien de Troyes’ 12th-century epic poem, and filmed on a deliberately artificial-looking soundstage, with perspectives as flat as medieval tapestries, preserves all the sweet innocence of the original and adds bright colors.

Where is the Friend’s House? (1987). The first masterpiece by Abbas Kiarostami to have a sizable commercial success in Iran, named after a locally famous poem by Sohrab Sepehry, is a miniature epic about a rural schoolboy trying to return a classmate’s notebook in a neighboring village and getting lost. Kiarostami makes it a philosophical parable about the adventures and ethical challenges of childhood itself.

Distant Voices, Still Lives (1988). Terence Davies’ impressionistic memories of his Liverpool childhood has been faulted for its emphasis on domestic brutality, family rituals such as funerals and weddings, and singing in pubs and parties. But as a lapsed Catholic, Davies endows all these everyday activities with the passion and intensity of luminous dreams.

Dead Man (1995). Jim Jarmusch reimagines the black and white Western the way a Native American during the 19th century might have viewed it — as a genocidal nightmare about the arrival of capitalism. He also creates a warm friendship between a dying accountant from Cleveland named William Blake (Johnny Depp) and a Native American outcast, Half Blood and half Blackfoot, named Nobody (Gary Farmer), and many visionary experiences in the American northwest.

Howl’s Moving Castle (2005). In Hayao Miyazaki’s inspired, animated adaptation of Diana Wynne Jones’ novel, people and objects undergo constant transformations according to their emotional and existential states of being. Furthermore, wisdom doesn’t so much succeed callowness as peacefully coexist with it. So the teenage heroine may get turned into a 90-year-old housekeeper for a youthful magician in a walking castle, but whenever she feels romantic stirrings for him, she becomes a teenager again —- a wonderful conceit.