From the August 11, 2006 Chicago Reader. — J,.R.

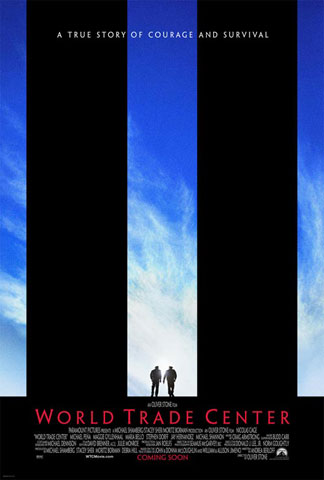

World Trade Center

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Oliver Stone

Written by Andrea Berloff

With Nicolas Cage, Michael Pena, Maria Bello, Maggie Gyllenhaal, Jay Hernandez, Armando Riesco, and Michael Shannon

“The Holocaust is about six million people who get killed,” Stanley Kubrick reportedly said to screenwriter Frederic Raphael in the late 90s. “Schindler’s List was about 600 people who don’t.” Assuming the quote is right, Kubrick’s speaking about the Holocaust in the present tense and about a movie made half a century later in the past tense suggests something about his priorities.

They probably aren’t the priorities of Oliver Stone, whose ruthlessly circumscribed World Trade Center isn’t about the 2,749 citizens of 87 countries who got killed in the 9/11 assault on the Twin Towers and who are mentioned only in a title when the movie’s over. It’s about two citizens of one of those countries who survived, John McLoughlin and William Jimeno, both real-life Port Authority policemen. The story of what they experienced is gripping and inspiring, but however true it is to their lives — it’s hard to imagine any two men on the planet could be as conventional as the filmmakers make these heroes — the way it’s told restricts what the movie can say about the larger tragedy.

McLoughlin (Nicolas Cage) and Jimeno (Michael Pena) got trapped by a cave-in between the two towers while they were heading for the north one to rescue people on the upper floors. Both were immobilized for many hours, though they were close enough to talk to each other. The movie, with a serviceable script by newcomer Andrea Berloff, is also about their families, who were waiting for news over the course of that chaotic day. (Maria Bello plays McLoughlin’s wife and Maggie Gyllenhaal plays Jimeno’s.) Practically everything we see of the attacks and their aftermath is filtered through the perceptions of these characters — and that of a former marine, Dave Karnes (Michael Shannon), a volunteer who helped rescue the heroes. (“We need some good men out there to avenge this” is the last thing we hear him say, and later we learn that he re-enlisted and served two tours of duty in Iraq.)

The movie’s being sold as an apolitical, nonideological human drama that will make red-blooded Americans want to stand up and cheer. Critics across the political spectrum are buying this contradictory package — David Ansen’s Newsweek cover story is a case in point. The film does work pretty well as an adventure thriller. I don’t question the legitimacy of celebrating the courage of these individuals and their families, and I can even tolerate the hokey nostalgia for World War II epics. But I’m troubled that the filmmakers have elided so much else of what happened on that day, as if it were some kind of neutral backdrop.

And I’m troubled that so many critics seem to think those elisions don’t matter. The most disquieting things I’ve read so far are some of the raves. Syndicated columnist Cal Thomas called the movie “one of the greatest pro-American, pro-family, pro-faith, pro-male, flag-waving, God Bless America films you’ll ever see.” Columnist Cliff May’s post at the conservative National Review Online site said, “Words I thought I’d never say: God Bless Oliver Stone.” But the mind-set at work is truly laid bare in a longer review on the same site. Kathryn Jean Lopez contrasts World Trade Center with another recent treatment of the 9/11 attack, a film about the United flight that crashed in a Pennsylvania field after passengers struggled with the terrorists: “Tasteful and well done as United 93 was, there was something about the movie that bothered me. The filmmakers showed me a bit too much of the terrorists. Calling home. Feeling sick. Praying. Forgive me my insensitivity, but I didn’t care to see them. I didn’t care if one or another of them was nervous in the minutes before the attack. It’s not terribly Christian of me, but I don’t really care about them — most especially in a movie that’s supposed to be about the good guys. I only wanted to see our 9/11 heroes.

“And in this regard, Oliver Stone delivers what United 93 didn’t. . . . [World Trade Center] is about us. It’s exclusively about the good guys. It’s about us when we’re heroic (those of us who are). It’s about us when we’re scared. It’s about us when we wake up in the middle of the night to go to work, listening to 1010 WINS (if you’re from New York City, there’s something extra-personal about this movie, and those attacks). It’s about us when we’re freaked-out kids who say mean things to our freaked-out mothers. It’s about a Marine who will drop everything to return to service. It’s about a team of rescue workers who will leave no man to die. It’s about our deep, abiding faith in God. It’s about our love of family, and the work we’ll do for them, and the joy they bring us. It’s about the irreplaceable, incomparable bond between a man and wife. It’s about the united outrage we feel when Americans are murdered. It’s about why we fight.“

If Lopez wanted a mirror she could have stayed home and watched kiddie shows about the good guys. But there are reasons other than Christian charity for wanting to know something about terrorists. And who’s she seeing in that mirror? Who’s this “we” who have a deep and abiding faith in God, love of family, etc.? She’s only outraged about the murdered Americans, failing to notice the foreign nationals and illegal aliens, including the service people who got up in the middle of the night and maybe even listened to WINS. She seems to suggest that our concern for Americans is supposed to supersede our concern for humanity, and so she’s privileging symbolism over individual people, which is exactly what the terrorists did. She’s simply ignoring the non-American victims — whom she’s treating like all the innocent bystanders the U.S. has alienated or killed overseas while claiming to be bettering their lives.

I find it hard to believe that Stone’s selectivity wasn’t intentional. His first prominent screen credit, which won him an Oscar, was for the screenplay of Midnight Express (1978) — Alan Parker’s masochistic bit of bombast about an American preppy serving time in a Turkish prison for possessing hash. The movie’s indifference to the treatment of Turks in the same prison suggests that Stone has always been closer to the National Review than his leftist credentials imply.

Many critics seem to see no contradiction between the progressive mantle Stone wears and the blatant misogyny of his Born on the Fourth of July and Nixon (which blame the warmongering instincts of Ron Kovic and the corruptions of Nixon on castrating mothers); the human Barbie dolls of Wall Street and The Doors; the homophobia of JFK; the adolescent patriarchal hang-ups of JFK, Nixon, Platoon, and Wall Street; or the cynical exploitation of sex and violence in Midnight Express and Natural Born Killers. And these critics often take very seriously Stone’s pompous film rhetoric: the last time I googled “Oliver Stone,” “Nixon,” and “Shakespearean,” I got 643 hits.

I’ve always seen Stone as an authoritarian demagogue, and World Trade Center hasn’t changed my mind. Its phantasmagoric imagination is less homoerotic than that of Midnight Express, but it yields comparable hallucinatory effects, including glittery evocations of Jesus carrying a plastic water bottle. The rousing war-movie ambience, familiar from Platoon, is even more prominent than the religious mysticism. And the blinkered worldview it promotes only encourages the worst instincts of people like Kathryn Jean Lopez — insularity and xenophobia — even as they congratulate themselves for what they call Americans’ essential generosity of spirit. But then we’re all susceptible to being seduced by this sort of narcissism — maybe because it helps push away the harsh reality of a world in which more and more people hate us.