The following was written for the Monthly Film Bulletin (April 1976, vol. 43, no. 507) — a publication of the British Film Institute, where I was serving at the time as assistant editor — and it follows most of the format of that magazine by following credits (abbreviated here) with first a one-paragraph synopsis and then a one-paragraph review. — J.R.

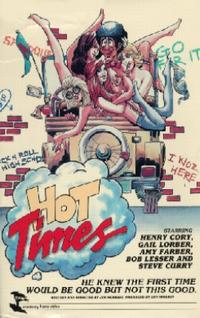

Hot Times

U.S.A., 1974

Director: Jim McBride

Cert—X. dist—DUK. p.c—Extraordinary Films. exec. p—William Mishkin. p—Lew Mishkin. assoc. p/p. manager/asst. d—Jack Baran. sc—Jim McBride. ph—Affonso Beato. col—Eastman Color. ed—Jack Baran. sd. rec—Nigel Noble. sd. re-rec—Jack Cooley. l.p—Henry Cory (Archie Anders), Gail Lorber (Ronnie), Amy Farber (Bette), Steve Curry (Mughead), Bob Lesser (Coach/Guru’s Voice), Clarissa Ainley (Kate, Gloria’s Mother), Bonnie Gondell (Gloria), Bette Muir (La Conchita), Jack Baran (Cab-driver Alex “Bushmaster” Mogul-muph), Lorenzo Mans (Jesús, La Conchita’s “Nookie Bookie”), Irving Horwitz [Mel Howard] (Director Potemkin), Rick Ross (Reggy), Jim McBride (Man at Elevator), Adrienne Mania (Archie’s Mother), Pious Applebaum (Dr. Spielberg), Rob Everett (Porn Actor), Shelley Plimpton (Patsy), Deirdre Baran (Girl in Phone Booth), Greta Starr (Porn Star). 6,807 ft. 76 min. Original running time—84 min.

A New York suburb, 1973. Archie Anders is awakened by a call from his girlfriend Bette, who wants to attend guru Maha-Vishnu’s New Year’s Eve Day Sunrise Service. Interested only in having sex with her, Archie rides with Bette to Shea Stadium, where she recalls that the event is being held in Yankee Stadium; while she listens to it on the car radio, Archie awkwardly tries to make love. She insists on driving back before he is satisfied, and after refusing in advance (for religious reasons) to sleep with him that night, she forces him out of the car when he threatens to take Ronnie to the prom instead. Unable to find another date, Archie arrives at school for the annual student-faculty basketball game. Disqualifying himself from the game when he has an erection, he goes into the girls’ locker-room with his friend Mughead; they hide in dustbins, and when he emerges, Archie is pulled by the cheerleaders through a cold shower while Mughead escapes. Hoping to have sex with Ronnie, he accompanies her to a motel where she acts in a porn film; after two actors are fired for improper ejaculation, Archie is enlisted as a replacement, but before he reaches orgasm the film crew has to flee from the motel manager. Returning home, he looks at Playboy, peeks at his sister while she steps out of a bath, and runs off when she summons their parents. Wandering through Times Square alone shortly before midnight, he meets Gloria, a promiscuous girl who agrees to have sex with him in fer flat. But when her “liberated” mother keeps interrupting their love-making, Gloria runs away. Archie dashes after her, and finally succeeds in having a complete sex act with her on the floor of the elevator. She leaves him there, drooling contentedly in a disheveled heap.

It is nearly seven years since David Holzman’s Diary – Jim McBride’s first film, made in 1967 – was reviewed in these pages; in the interim, few filmmaking careers have been as checkered. After this fictional filmmaker’s diary came My Girlfriend’s Wedding (1969), an intriguing companion-piece that offered a “real” account of the director’s life at that period, and then a strikingly original SF film, Glen and Randa (1971), that mixed documentary and fiction in a Godardian manner conjuring a post-Atomic civilization as seen by a Flaherty or a Rouch; neither of these has been distributed in this country. Then came two more projects which never reached fruition – Gone Beaver, an extremely ambitious large-scale Western for BBS about early American trappers and Indians, for which a virtually invented language of “trapper talk” was devised, and The Brothers Frigidaire, a “spy musical” which never got beyond the treatment stage. If A Hard Day for Archie, McBride’s next project, has finally reached the screen as Hot Times, its own career has been no less difficult: altered by its producers to avoid an “X” rating in the U.S., its dialogue has been extensively bleeped out with the sound of a cuckoo, and several shots have been masked with a technique similar to that used in Scope films on TV; the British censors have removed some footage and the British distributor has cut a bit more for double-feature programming. If Hot Times appears to be McBride’s least successful film, even apart from these losses, it nevertheless has a fascination nearly equal to the others, as an almost Faustian effort to achieve the impossible — to ridicule the basic precepts of the sex movie out of existence, having and conveying as much fun as possible in the process. The strategies for attempting this are diverse. First of all, there is an off-screen irreverence that begins with the wonderful accapella song behind the credits, continues with Mughead’s ingenious narration, and culminates in the hilarious American Grafitti parody extending the characters’ subsequent lives with Byzantine notations which weave a plot six times as complicated as anything in the film proper. There is the inspired use of language throughout – a weird blend of Fifties slang, New York jive with ethnic trimmings, and a sheer enjoyment of obscene extravagance, all played against the notion of teenage characters derived from Archie Comics and propounded on a semi-abstract terrain evocative of Preston Sturges and Robert Crumb. As in all McBride’s films, talk becomes a kind of exotic tribal ritual: “Hey Ma, he’s making a milkshake on the sheets”, Archie’s sister complains of his masturbation; “Forget it, gringo, this is canned goods,” says a Latin-American pimp alluding to his virgin sister; “You scum-ducking pig,” growls a Russian porn director, in homage to One-Eyed Jacks; “Get a gander at this goose,” declares a cab-driver (played with great gusto by Jack Baran) reintroducing Ronnie to Archie. Equally playful are absurd breaches of verisimilitude (the lugubrious “sexy” radio patter heard in Gloria’s flat continuing inside a closed elevator), a profusion of throwaway gags (“Gee Archie, that was better than Last Tango in Paris,” Gloria says rising from the elevator floor), and many in-jokes: McBride himself appears twice in the same elevator, as though to mock further the hero’s inane efforts to have sex at any cost — “Down?” he asks, while Gloria says “Up!”, and later arriving with his dogs to witness Archie slobbering alone on the floor and remark, “It’s about time.” Other “home movie” aspects include the appearances of several collaborators prominent in earlier McBride films, T-shirts advertising the unmade Gone Beaver, and occasional forays into Godardian “documentary” (slips in dialogue delivery, Archie in Times Square on New Year’s Eve). But quite apart from countless local and personal references, what keeps this bizarre movie alive, goofy and unpredictable through all its various lapses –- overplayed scenes, Muzak punctuations, and an irrelevant fantasy visit to a sauna which appears to have been inserted as a commercial after-thought – is its spirited and virtually unwavering demonstration that life and sex movies seldom correspond. Pulled through a cold shower by naked cheerleaders, Archie can’t decide whether he’s fulfilling a dream or enduring a nightmare; an actor in the porn movie persistently chews gum while executing his sexual duties; Bette squeals. “Oh Archie! I think I had an orgasm!”; and Gloria gamely concedes that her mother may be sexually liberated, but just the same “she’s a pain in the ass.”