This essay was comissioned by the French magazine Trafic — founded by the late Serge Daney shortly before his death, and still going strong today — where I’ve served for many years as one of the advisory editors. Their 50th issue, published in the summer of 2004, was devoted to various answers to the Bazinian question, “What is Cinema?” This is also the title essay in my 2010 collection, published by University of Chicago Press. — J.R.

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia

by Jonathan Rosenbaum

What is cinema?

Before one can even start to answer this question, it becomes necessary to acknowledge that one can’t formulate precisely the same definition of cinema for France and for other countries. And the reason why one can’t should be obvious: in France, an important part of this definition pertains to film as an art form—-a distinction that is generally perceived elsewhere only as a minority position, and sometimes even as an elitist one. But if, on the other hand, one were to ask the question, “What is cinephilia?”, it starts to become easier to come up with a definition that applies to everywhere. A seeming contradiction, it can perhaps be explained by saying that the “cinema” in “cinephilia” is not quite the same thing as “cinema” seen as a self-sufficient term, without reference to social forms.

Consequently, to answer the question, “What is cinema?” from the vantage point of a cinephile living in Chicago, it is difficult to be very optimistic, but to answer “What is cinephilia?” from the same vantage point is a much more agreeable activity.

Regardless of where one is, whether one is speaking rhetorically or literally, there is usually the presumption that “cinema” is something that happens inside a theater, on a screen, which one watches with other people after purchasing a ticket. But more and more often these days, I’m beginning to think that this activity in much of the world currently represents an idealist model of what cinema consists of, and that it is no longer a practical description that applies to the experience of most people.

If more people today view films on television screens than inside theaters, one can see why this theatrical model is already something of a misrepresentation–perhaps even a nostalgic holdover from the past. Whether they’re watching films on TV (with or without commercial breaks, cuts, alterations of the original speed or formats) or watching videos or DVDs that they’ve purchased or rented, the decision to see a film and how one goes about implimenting that decision are already substantially different from what they meant traditionally.

Furthermore, insofar as films often figure as the central parts of advertising campaigns selling much more than films, it become important to ask precisely where the existential meaning of a film begins and ends-—assuming that it can be said to begin or end anywhere in the affective life of the spectator. For it’s surely obvious by now that we’re all deeply affected by films that we never see.

This Christmas season, when I went to a branch of the Chicago post office to renew my passport, I saw that a placard on the service counter advertising various priority-mail bundles also had a tie-in ad for The Cat in the Hat, a studio live-action children’s movie released last week. I haven’t seen the film—-which is based on a book by Dr. Seuss, the penname for Theodore Geisel, a writer whose works are less known outside the U.S.—-and I have no interest in seeing it; everyone I know who’s seen it despises it. But this doesn’t mean it won’t continue to have a strong presence in my everyday life. Indeed, seeing that ad in the post office made me reflect that the Stalinist dream of a planned culture may now have become realized more throroughly in contemporary American culture than it ever was in Russia. (The only previous theatrical film I know connected to Geisel’s work is The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T (1953), a childhood favorite of mine, and when I once had a phone interview with him a quarter of a century ago, he told me that he was so unhappy with the experience of working on that film that he wrote only for television ever since, where he had more creative control. Now that he’s dead, however, it’s obvious that his estate doesn’t share his compunctions.)

I have seen 21 Grams, a hyperbolically depressing art film by Alejandro González Iñárritu that has been receiving a lot of mainstream exposure lately because of its cast (Sean Penn, Naomi Watts, Benicio Del Toro) and a sizable advertising budget. Thanks to this budget, an offscreen speech by Penn at the end of the film has been getting what seems to be more attention from the press than all the recent civilian deaths in Iraq and Afghanistan combined. The speech goes as follows: “They say we all lose 21 grams at the exact moment of our death…everyone. The weight of a stack of nickels. The weight of a chocolate bar. The weight of a hummingbird…”

Part of the attention paid by the press to this speech is to point out that this statement is completely untrue. But, with the recognition that “there’s no such thing as bad press,” this hasn’t prevented Focus Features from sending out, on consecutive days late last month, èxpress packages with transparent bags of inflated plastic containing (a) a stack of five nickels, and (b) a chocolate bar inside a wrapper advertising 21 Grams, and (c) a made-in-China “hummingbird”. I assume that if Focus Features were also capable of determining and then inserting the exact moments of our own deaths inside an inflated, transparent plastic bag, complete with a tie-in to the title of their film, they’d be sending that along to us members of the press as well, and probably gift-wrapping it in the bargain.

I try to guess how many packages containing 25 cents each were sent to members of the press, how many homeless people might have been fed with the same amount of money, and how much anyone was directly or indirectly persuaded to see this film because of this ridiculous and obscene advertising scheme. Are there any limits to what promotional departments will try, and do they even care whether they succeed or not? After all, a few years ago, in order to promote Peter Chan’s The Love Letter (1999) —- a Hollywood comedy that I liked far more than 21 Grams —- DreamWorks actually sent out anonymous love letters to critics. Each one appeared to be written on an old-fashioned typewriter with a faded ribbon, much like an unsigned letter that circulates in the film, and this was done so persuasively that I’m embarrassed to confess that I was fooled into thinking it was a real letter addressed to me until I attended a press screening of the film, saw the same letter onscreen, and realized the emotional rape that DreamWorks’ publicity department had cheerfully perpetrated on my feelings.

What I like to ask now is, was that imitation of a love letter “cinema”? If it wasn’t, what was it? And if it was, was it more cinematic or less cinematic than Chan’s film?

II

It’s sad in some ways to see the old paradigms of cinema dying in the U.S. But the emerging paradigms of cinephilia in this part of the world-—which could significantly be almost anywhere else in world—-are exciting to me, and I don’t believe that we’re obliged only to lament the new state of things. If we start to think of cinephilia less as a specialized interest than as a certain kind of necessity—-an activity making possible things that would otherwise be impossible—-then it starts to become possible to conceive of a new kind of cinephilia in which cinema in the old sense doesn’t exactly disappear but becomes reconfigured (something that, after all, has been happening with a certain constancy throughout the so-called history of “cinema”).

The best DVDs being made today–DVDs of the best or most important films from the past as well as the near-present–are available to spectators all over the world, especially those who get into the habit of ordering them over the Internet, and sometimes from other countries. Today, for instance, it’s possible to see the beautiful colors of the second part of Ivan the Terrible correctly, accompanied by superb historical documentation, anywhere one has a DVD player and the Criterion edition of the DVD, with commentaries by Yuri Tsivian and Joan Neuberger. Admittedly, this isn’t the same thing as seeing a 35mm print of the film with incorrect colors and with less comprehensive documentation in Paris or New York 30 years ago, but can we really say with assurance that we’re necessarily less fortunate today? Obviously the rules of the game are changing, both for the better and for the worse, and the fact that spectators in small towns will mainly choose to watch the masterpieces they couldn’t see before in their own homes is only one reflection of current habits and practices. The disappearance of what Raymond Bellour has called “le texte introuvable” and all the fugitive magic that this implies has to be weighed against the appearance of the film that one can now possess and casually browse through like a book, recovering favorite passages at will. Can films seen on television screens change one’s life as films on giant theatrical screens could? I think so, but almost certainly not in the same ways, and possibly in certain new ways that are still evolving. Who’s to say that future ciné-clubs can’t be devoted to screening DVDs in casual surroundings—-storefronts or schools, for example? Or maybe they can remain in homes while regaining some of their former status as public events.

In fact, only a few days after I saw ads for The Cat in the Hat in a Chicago post office, I attended a political meeting a few blocks from my apartment where I met for the first time about two dozen other people who despise George W. Bush as much as I do, and who want to find ways of getting him out of office. Their ages ranged approximately from early 20s to late 70s, and the occasion of our meeting was an opportunity to watch a film on DVD called Uncovered: The Whole Truth About the Iraq War — made explicitly by and for a rapidly growing and highly effective activist group called MoveOn, which currently has over two million online subscribers and which had organized the party, as well as over two thousand other parties like it that were being held in the U.S. at precisely the same time, most or all of them in private homes.

It’s of course far too early to know if we have a chance of getting Bush voted out of office next November, but it was an evening that gave me some hope. Strictly an agitational documentary detailing the lies and deceptions of the Bush administration, the film was neither presented nor received as art. Yet it afforded a communal experience that I think could be honestly and fairly described as a certain kind of cinema, and I have little difficulty in imagining such an experience transferred to some of the more conventional gratifications of cinephilia.

At one point, after we all watched the film in our hostess’s living room and listened on a speaker phone to members of other groups at other parties around the country, we discussed how the film could be more widely seen in Chicago. Some members proposed —- a little naively, I thought —- that some local movie theaters be persuaded to show it as soon as possible; a prominent art theater as well as a commercial multiplex were suggested. I proposed, as an alternative, more partylike gatherings such as this one, where the film could be discussed and no one had to worry about convincing local exhibitors to change their booking schedules or worry about profits. I also suggested that one can envisage travelling programs of films on DVDs (and not only political or agitational films) that can be sold to individuals after the screenings, the same way that certain singers or musicians now sell CDs of their work after giving live performances. Ciné-clubs of this kind automatically have a potential that wouldn’t be conceivable if one had to worry about about acquiring 35-millimeter prints and cinemas or auditoriums to show them in.

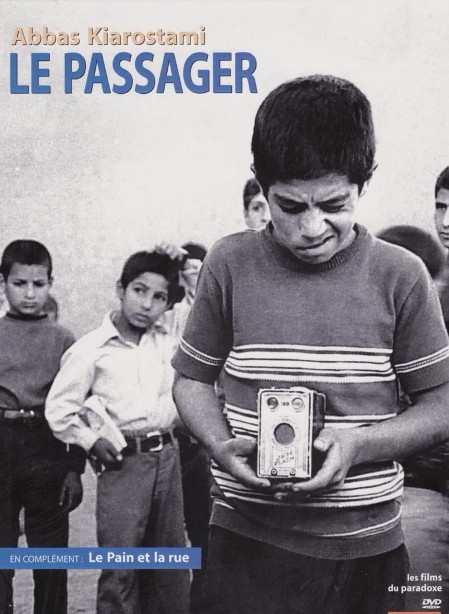

The issue, really, is how much arrangements of this kind can be made by audiences and programmers rather than by large companies. Will they entail new forms of the cinephiliac imaginary? Undoubtedly they will, although it is surely too early to predict all the new forms that this imaginary will take, except to stress that it will combine old and new materials, channels, ideas, experiences, technologies, and authors. In my first book, Moving Places: A Life at the Movies [published in France as Mouvements], almost a quarter of a century ago, I was already lamenting the end of a certain kind of cinema as well as a certain kind of theater, and a certain kind of social interaction that went with both. But it would be vain and foolish to claim that things of this kind ever end entirely, even if they change radically beyond our childhood recognition of them. The basic point is that there are still cinephiles much younger than myself who are full of excitement about films made even before the glory days of Louis Feuillade and Yevgeni Bauer (whose mise en scene in the 1913 Twilight of a Woman’s Soul and the 1915 After Death are elegantly described by Tsivian on a new American DVD called Mad Love); and this situation isn’t ever likely to change, even if the places and contexts where these films are seen and understood become radically transformed. And even if we can no longer claim with the same confidence that we can possibly know what the cinema is in all its manifestations and forms —- any more than we could ever have made such a claim for literature or theater, at least if we acknowledge that comprehensive history isn’t the same thing as contemporary access and fashion —- we at least have the sophistication today of being able to recognize our ignorance to a greater extent than we possibly could during the so-called past Golden Ages of the past, such as the 1920s, 1960s, and 1970s. Even during the last of these decades, when Kiarostami was already making such masterpieces as The Traveler and Two Solutions for One Problem, most of us knew next to nothing about Iranian cinema, but today —- because we know now that we knew nothing then —- we’re more apt to admit that there are possibly things going on today that we also don’t know about.

At most, one can mention a few utopian principles as a starting point. Recently encountering the web site of an organization called ELF (an acronym for Extreme Low Frequency that can [or once could] be found at www.extremelowfrequency.com), run by the independent filmmaker Travis Wilkerson — devoted to showing such films as Thom Andersen and Noel Burch’s Red Hollywood, John Gianvito’s The Mad Songs of Fernanda Hussein, Wilkerson’s own An Injury to One (a remarkable experimental film exploring the 1917 lynching of union organizer Frank Little in Butte, Montana), and Billy Woodbury’s Bless Their Little Hearts, to people “in theaters, homes, and schools” —- I come upon a sort of manifesto that matches many of my own convictions. Let me cite the passages that strike me as being most relevant:

“The cinema is in crisis. It neither apprehends our reality honestly nor does it aid in imagining a different kind of future. It is suffocated by a set of anachronistic conventions dictated by the agents of commerce. Extreme Low Frequency (ELF) is a corrective action. It constitutes a conscious cine-rebellion. The chief activity of ELF is the propagation of new cinema waves. These waves will take an endless number of shapes, and confront an endless battery of problems. The new cinema mustn’t be an `ism,’ nor an academic moment. To achieve its aims, the new cinema must become permanent.

“…The new cinema doesn’t concern itself with technological debates, particularly the antagonisms of analogue against digital. It employs, without prejudice, any and all tools available to it.”

“…The new cinema can exist only in a state as (un)finished and (in)complete as the world it intends to mirror and engage.

“…The new cinema refuses to recognize national borders. It identifies itself neither as fiction nor as documentary. Likewise, it is unconcerned with genre, which is useful only to the agents of commerce.

“…The new cinema will strive to return popular culture to the people themselves.

“Above all else: while studying the old, create the new.”

These principles imply that, before one can even begin to answer the question, “What is cinema?”, one first has to determine, “Whose cinema?” And maybe also, “Where?”–at least if we dare to suggest that cinema is that indeterminate space and activity where we find our cinephilia stimulated, gratified, and even expanded. And if the audience can find ways again of claiming a certain cinema as its own, even if that means moving out of theaters, the possibilities start to become limitless. In spite of everything we might lose, and would hate to lose, we still have no way yet of determining all we might gain.

—Trafic #50 (“Qu’est-ce que le cinéma?”), été 2004