From the Chicago Reader (June 29, 2007). — J.R.

SICKO ***

DIRECTED AND WRITTEN BY MICHAEL MOORE

One of the standard charges leveled against Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11 (2004) was that it was preaching to the converted. I don’t think this is entirely true: Moore credits himself with helping to turn this country against the war in Iraq, and if we look at when the opinion polls started to shift, his claim doesn’t seem entirely unwarranted. The sad fact is that his screed scored in part because it delivered some basic facts about the aftermath of 9/11 that the mainstream news media had failed to put across.

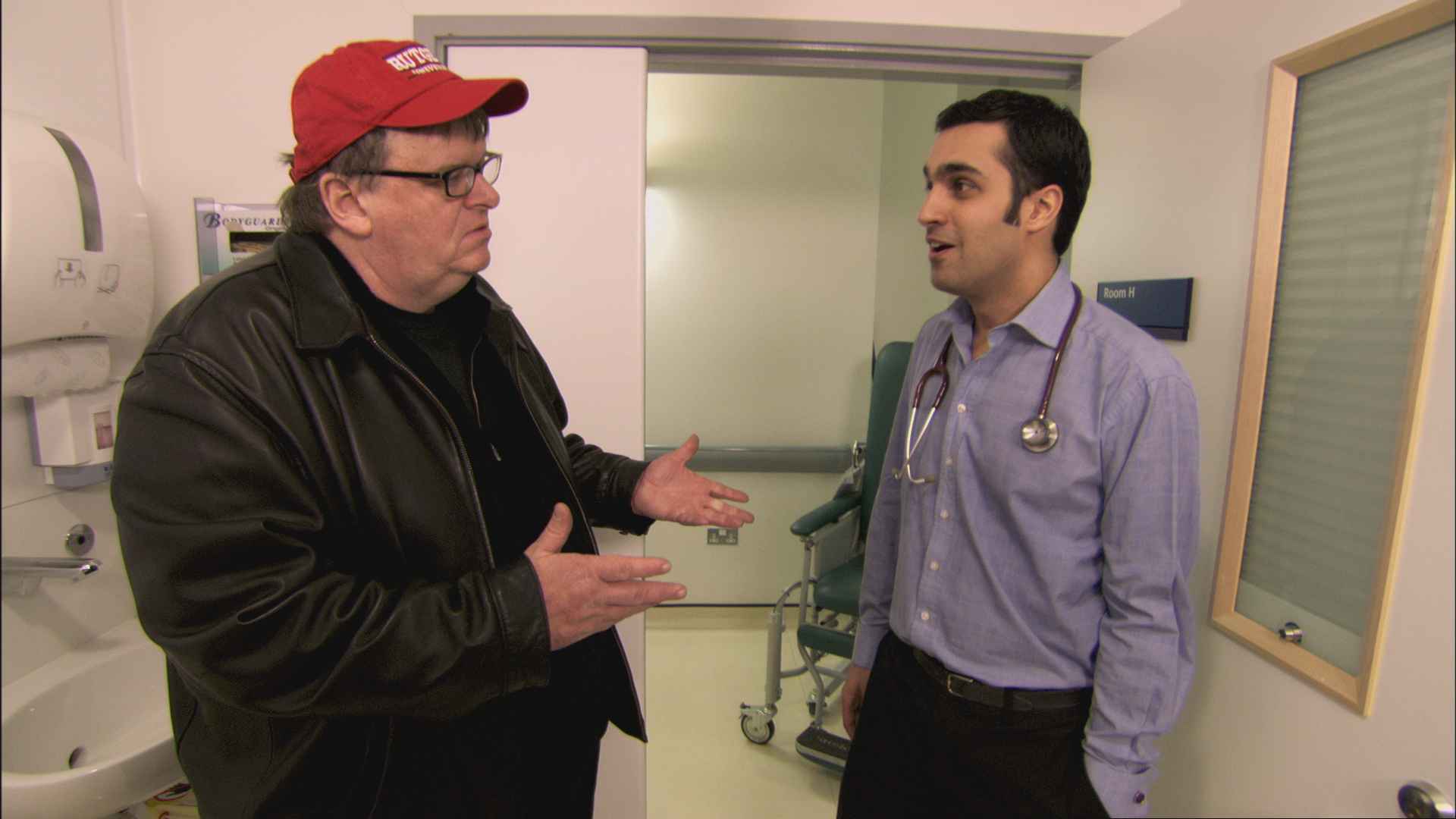

For better and for worse, Moore’s Sicko scores for similar reasons. It spends more than two hours attempting to preach to the unconverted that (1) this country’s health care system is a disgrace, especially when it comes to medical insurance, and that (2) it could easily be much better. There are fewer jokes this time around, and Moore makes a point of not even appearing on-screen for a good 40 minutes, putting more emphasis on his arguments and less on his comic persona.

It’s an honorable tactic and the arguments are strong. But when he finally turns up in the flesh, there’s something even more rancid than usual about the way he plays dumb. We’re forced to arrive at one of two possible conclusions, each fairly alienating: either Moore is correct about the majority of his audience being a pack of numskulls, necessitating his Health Care 101 approach, or he’s wrong, which means we have to pretend to be dumb to play along with him.

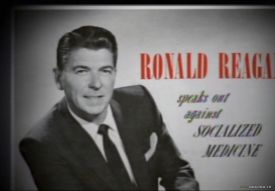

After devoting a good half of his film to horror stories about Americans with no health insurance (just a couple of examples) or those who have it and still get screwed over (quite a few), he offers some eye-opening tours of national health services in Canada, London, and Paris, asking all the right know- nothing questions about how a government doctor in London can drive an Audi and live in a million-dollar home or how one of his Parisian counterparts can routinely make personal house calls for free (with Moore and his camera crew along for the ride on one). Then, back in the U.S., he criticizes Hillary Clinton for working both sides of the street, praising her for trying to set up a national health care system, then dissing her for being silenced by the medical insurance lobbyists; he provides a useful and often hilarious history of propaganda against universal health care sponsored by the American Medical Association (with a little help from Ronald Reagan); and he explains how insurance companies (with help from Nixon and Bush) became corrupted by unchecked power.

Finally he zeroes in on a few 9/11 rescue workers who’ve developed respiratory or post-traumatic stress problems and the maddening reasons they can’t get adequate help for them.

This leads logically to some classic Moore stunts. He charters three boats and fills them with the patients whose case histories he’s been presenting, then takes them to Guantanamo Bay, where suspected terrorists incarcerated at the naval base receive excellent free medical care. He asks vainly over a bullhorn if his newly formed community of screwed-over American victims can get treated too. After the predictable silence is broken by a siren from the base, he proceeds with his hard-luck cases to Havana, where he asks a group of men playing dominoes outdoors, “Is there a doctor here in Cuba?” — insulting the locals while playing to his movie audience. Concluding that “it seems like there’s a doctor on every block,” he gets his patients free and apparently expert medical help at a Havana hospital, clinching his argument.

As a grateful recipient of the benefits of universal health care for most of a decade, when I lived in France and England in the 70s, I don’t need to be converted by Moore, and I know that many others who have never lived abroad feel the same way. But when it comes to evaluating national health in those two countries, Moore comes up a bit short.

Because he insists on delivering his message in such broad strokes, his picture of health care in Paris and London is so rosy that he can’t even allow for the possibility that any patient in either city could ever receive less than perfect treatment. Nor does his view of things account for patients paying for care there (the only two times I stayed in a hospital overnight in London and Paris I paid for the privilege).

Once, while staying in London, I discovered I had appendicitis, but being ineligible for a free appendectomy on short notice — because the condition wasn’t acute — I made the decision to pay to have my appendix removed soon afterward. Another time, when I developed a painful toothache on a national holiday, I had to pay to have a dentist come to my flat to treat it that day. There’s nothing exceptional about such experiences — people choose to operate outside the national health for a multitude of reasons. But admitting nuances doesn’t fit Moore’s agenda. It’s perfectly understandable that he doesn’t want to focus on exceptions to the rule, but his playing the country bumpkin while depicting Paris as heaven on earth gets to be a bit much. So does his use of a clip of a British broadcaster saying, “Even the poorest people in England are healthier than the wealthiest people in the U.S.”

All the studied dumbness notwithstanding, Moore does make some cogent arguments about how we could and should reconceptualize the very idea of “socialized medicine.” Former British Parliament member Tony Benn — the most eloquent talking head in the film — argues that “it all began with democracy. . . . What democracy did was to give the poor the vote.” Along with Moore, he explains how national health in England — begun in 1948 and as uncontroversial there as allowing women to vote — grew out of World War II: “If you can have full employment by killing Germans, why not have full employment by building hospitals?” He adds, “I think democracy is by far the most revolutionary thing in the world,” encouraging us to reflect that it wouldn’t occur to most of us to call the American educational system, postal service, public libraries, fire and police departments, or military “socialized.”

So why do we insist on depriving ourselves of the benefits of national health? Presumably for the same reason an unpopular war gets escalated — so a privileged few can profit. “People in debt become hopeless,” Benn says, “and hopeless people don’t vote.” As Moore shows us in another clip, George H.W. Bush once said, “If you think socialized medicine is a good idea, ask a Canadian.” Of course, he was assuming we wouldn’t ask. That was before the Internet and Michael Moore.