From the Chicago Reader (June 7, 1996). — J.R.

Mission: Impossible

Rating * Has redeeming facet

Directed by Brian De Palma

Written by David Koepp, Steven Zaillian, and Robert Towne

With Tom Cruise, Jon Voight, Henry Czerny, Emmanuelle Beart, Jean Reno, Ving Rhames, Kristin Scott-Thomas, and Vanessa Redgrave.

The Phantom

Rating * Has redeeming facet

Directed by Simon Wincer

Written by Jeffrey Boam

With Billy Zane, Kristy Swanson, Treat Williams, Catherine Zeta Jones, James Remar, and Cary-Hiroyuki Tagawa.

My Favorite Season

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Andre Téchiné

Written by Téchiné and Pascal Bonitzer

With Catherine Deneuve, Daniel Auteuil, Marthe Villalonga, Jean-Pierre Bouvier, Chiara Mastroianni, Carmen Chaplin, Anthony Prada, and Michèle Moretti.

I think that one never grows up emotionally. We grow up physically, intellectually, socially, and even morally but never emotionally. Recognition of this fact can be either terrifying or deeply moving. Everyone handles it in their own way. — Andre Téchiné

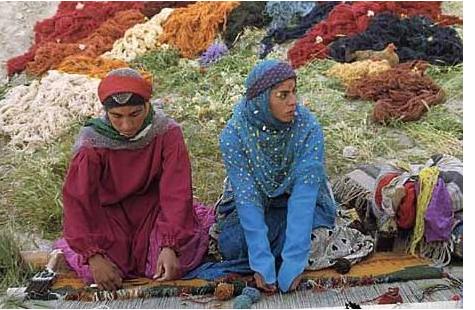

The principal pleasure of the Cannes festival for me was a two-week vacation from the “fun” of American movies. Maybe this fun — which points to our inability to grow up emotionally — would seem less oppressive if it didn’t also inform the American experience of news, politics, fast food, sports, economics, education, religion, and leisure in general; this kind of fun is less an escape than an enforced activity, a veritable civic duty. Yet at Cannes I was thrilled by the exploding colors of a fairy tale about a real nomadic tribe of Iranian carpet weavers (Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s Gabbeh); the mysterious questions raised by a remake of the silent French serial Les vampires, with Maggie Cheung in black tights (Olivier Assayas’ Irma Vep); the Ibsenian shocks and shadings of Mike Leigh’s Secrets and Lies, with a plot surprisingly similar to that of A Family Thing; a French Raul Ruiz comedy with Marcello Mastroianni that dovetails twice-told stories suggesting late Bunuel (Three Lives and Only One Death, just picked up by New Yorker Films); a galvanizing melodrama about sexual and religious suffering in Scotland in the 1970s that alternates dizzying handheld camera work (by Robby Müller) with gorgeous landscape “chapter headings” (Lars von Trier’s Breaking the Waves); a charming chamber piece by Bernardo Bertolucci with a literate script in English, cowritten by Susan Minot, that finally puts his oedipal hang-ups behind him (Stealing Beauty, opening here late this month); a beguiling piece of African folklore equating human lives and trees, both traversed by lyrically choreographed pans and cranes (Flora Gomes’s Po di sangui); and a contemporary gangster film whose handling of music, treatment of capitalism, episodic narrative, and exquisite camera placement suggest a Taiwanese version of Brecht’s Rise and Fall of the Town of Mahagonny (Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Goodbye South, Goodbye). In short, no “fun” at all — which is why you’ll have to wait a year or more to see most of these items — but loads of un-civic-minded, edifying enjoyment.

Back in this country, I’ve had to settle down to chores like Mission: Impossible (another TV spin-off, this one glorifying the CIA the way De Palma’s The Untouchables glorified the FBI) and The Phantom (another comic-strip spin-off, this one conjugating Indiana Jones and Batman to yield Billy Zane looking uncomfortable in purple mask and tights). Happily, I’ve also been able to see a movie that doesn’t equate life with the experience of old TV shows and comic strips — a family drama by Andre Téchiné about not being able to grow up emotionally, My Favorite Season (Ma saison préferée). (Made three years ago, it’s apparently surfacing this week at the Music Box because of the commercial success of Téchiné’s more recent Wild Reeds. Still more recent is Téchiné’s Les voleurs, one of the major films at Cannes this year I managed to miss, with the same two leads as My Favorite Season, Catherine Deneuve and Daniel Auteuil.)

In a way I’m ill equipped to deal with these three pictures since I’ve never followed closely the career of Andre Téchiné — at least after his first four features (1969-1978), which discouraged me from seeing his next five (1981-1991) — or the Mission: Impossible TV show (1966-’73) or the Phantom comic strip (1936-’96), though I must have idly sampled the last two countless times. Consequently I can’t judge how Mission: Impossible and The Phantom adhere to their traditions, but the self-destructing tape recorder barking out instructions at the beginning of each TV episode of Mission: Impossible is emblematic of how both action movies are expected to function: say what they have to say or do what they have to do and then vanish without a trace.

This task is performed so efficiently in the Mission: Impossible movie that I generally couldn’t follow the plot or characters for more than a sequence or two at a time, but I never felt I was missing much. As far as I could tell, the only reason these people and intrigues exist is to set up the action scenes — not to keep the “free” world safe for democracy or to say anything about the human condition. So as long as the moment-to-moment spectacle absorbed me, I couldn’t have cared less why Tom Cruise had such a sour expression or could make floppy disks disappear like coins or playing cards — or why Billy Zane in his purple tights kept grinning when there wasn’t any reason to. In one morphing stunt Jon Voight mutates into Cruise wearing a Jon Voight mask, which seems emblematic of how each character could just as well be any other. If Treat Williams were the Phantom and Billy Zane the capitalist villain would any significant nuances be lost? And if Emmanuelle Béart and Vanessa Redgrave exchanged roles in Mission: Impossible isn’t it even possible that something would be gained?

Even if the TV spin-off is slicker than its comic-strip partner — De Palma’s hackwork is always more stylish than most other people’s — the clunkiness in The Phantom has more charm. Mission: Impossible belongs to Cruise (who doubles as coproducer) more than De Palma, and The Phantom belongs mainly to a bunch of banks, so why should we pretend that either brainless entertainment has or needs any sort of artistic coherence? The beautiful simplicity of Les vampires — or Irma Vep, for that matter — is that it was turned out so fast that it functioned like automatic writing, spinning out its own kind of dream language, its own poetry of the unconscious. But with all the millions behind Mission: Impossible and The Phantom, every effect is so calculated that only the conscious minds of filmmakers and viewers are engaged — and not by very much or for very long.

Split into four chapters corresponding to the four seasons but titled according to the movements of an aging, ailing, illiterate farm widow (Marthe Villalonga) in southern France as she approaches death — “the departure,” “the false step,” “the next step,” “the return” — My Favorite Season is concerned mainly with her two neurotic, middle-aged children. Emilie (Catherine Deneuve) is a frigid married lawyer with two teenage children, and Antoine (Daniel Auteuil) is a bachelor brain surgeon in denial; both are “modern” overachievers who’ve settled in Toulouse and have sustained throughout their unhappy lives an unrequited passion for each other. Behind the opening credits is a pan across a painting of two pairs of cherubic Siamese twins, signaling at the outset that these dysfunctional siblings, warily brought back together by their mother’s worsening condition, can never recover the symbiosis they knew or at least imagined as children.

A central clue to what Téchiné has in mind is the name Emilie; he’s clearly thinking of the Bronte sister who wrote Wuthering Heights — his fourth feature was The Bronte Sisters (1978). This doomed yet rapturous relationship between a brother and sister recalls Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury and Cassavetes’s Love Streams, but the style is that of Téchiné’s first mentor, Ingmar Bergman — the poet of torment who always views neurosis from the inside out. (Bergman was a less felicitous influence when Téchiné started his directing career with the unbearable 1969 Paulina s’en va, but over the next quarter of a century the former Cahiers du Cinéma critic would learn to replace film experience with life experience.) Like both Cassavetes and Bergman, Téchiné is digging for highly personal discoveries, using his actors as well-honed shovels, and not always bothering to clarify how much of the action is happening inside the characters’ turbulent heads. (For all Auteuil’s brilliance, the movie’s biggest revelation is Deneuve — a fashion plate specializing in surfaces who’s allowed her responses to be sharpened into blades.) Yet the sheer sensuality and generosity of this investigation also calls to mind Jean Renoir; Téchiné shot every scene simultaneously with two cameras, and as he noted, “the coexistence of two cameras corresponds to the very subject of the film, the delicate interplay of two actors.”

This is the center of My Favorite Season, but by no means the entire film or the extent of its curiosity; it’s a movie about three generations, not two. Also prominent — and fully fleshed out — are Emilie’s estranged husband and law partner (Jean-Pierre Bouvier); their two kids (Chiara Mastroianni and Anthony Prada); and the Moroccan secretary (Carmen Chaplin) Emilie shares with her husband — a relatively untroubled ingenue who’s ambiguously adopted or appropriated by every member of her household and who clearly inspires the North African music heard over the beginning and end titles.

All these characters have their own claims to make, on our attentions and on one another, and they’re a much too unruly and unwieldy bunch of individuals to add up to an easily digestible or fully accountable movie. Too many unresolved or obscurely defined elements overflow the simple design provided by the dying mother and her two children, and the confounding mysteries and complications of life take over. The sheer immediacy of personal experience intrudes as well; one scene in which the mother faints in the field outside her house has the mystical radiance of a moment in Tolstoy.

As critic Kent Jones puts it, Téchiné has “a novelistic sense of story, a musical sense of rhythm, and a filmic feeling for the beauty of people in motion. I think his toughness is the main reason for his relative invisibility in America, where we customarily expect cinema to provide us with some sort of comfort” — the sort of preadolescent comfort that derives from, say, the helicopter chasing the train in Mission: Impossible or the hero and heroine leaping from a boat-plane onto a galloping horse in The Phantom. By contrast, My Favorite Season can provide us only with people, most of them discomforting to a fault. In other words, not much fun by American standards. Yet the excitement is such that I feel like I’m back in Cannes.