This comes from the top of my 1999 ten-best column for the Chicago Reader in January 2000. — J.R.

Eyes Wide Shut. Part of what irked some reviewers about Kubrick’s eccentric masterpiece is one of the things I treasure about it -– its distance from its own period. This quality is shared by at least two sublime testament films released in the 60s to similar amounts of scorn, Carl Dreyer’s Gertrud (1964) and John Ford’s 7 Women (1966). Both of them are clearly set in earlier periods; Kubrick’s is purportedly set in present-day New York but was adapted from “Traumnovelle,” a 1926 novella by Arthur Schnitzler set in prewar Vienna. All three depend on highly stylized and subjective renderings of time and place that become an essential part of their memory-laden textures. (To correct two factual errors in my original review: the prewar setting of Schnitzler’s novella can be gleaned from a reference to Bohemia, not Czechoslovakia, and Schnitzler wasn’t a friend of Freud’s but an ambivalent contemporary reader of his work, though Freud did once refer to Schnitzler as his “doppelganger,” apparently because they held some similar notions about psychology.)

Like many an artist before him, Kubrick went from being part of his own time — for better and for worse, Dr. Strangelove (1964), 2001 (1968), and A Clockwork Orange (1971) are uncannily in tune with the preoccupations of their periods — to being in a time frame of his own, which is apparent in Barry Lyndon (1975), Full Metal Jacket (1987), and Eyes Wide Shut. (His 1980 The Shining is arguably a throwback.) He gives almost no attention to the particulars of living in New York in the 90s, since his “contemporary” Manhattan is basically a throwback to the 60s, the last time he lived there — which may be one reason this movie offended a few New York egos.

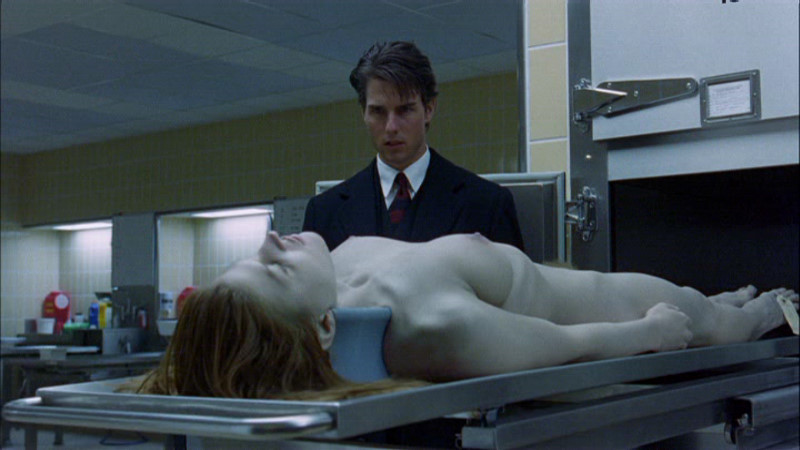

Eyes Wide Shut has a lot to say about the psychological accommodations of marriage — and has a sunnier view of human possibility than any other Kubrick film, in spite of all its dark moments. It depends on a sense of the shared mental reality of a couple that almost supersedes any sense of their shared physical reality, a strange emphasis that’s probably the source of most of the confusion felt by everyone in the course of processing the story. (A similar sense of shared mental reality can be found in the title characters of Schnitzler’s startling, almost equally masterful 1913 novella “Beatrice and Her Son.”) A list of the things we never learn about the characters is at least as long as the list of things we know with any certainty. We remain in the dark about how the wife happens upon the mask worn by the husband at the orgy, about whether he tells her the entire truth about his adventures, about the accuracy of Ziegler’s account of many of those same adventures, and even about whether they happen outside the husband’s imagination. Yet there’s never any doubt about what transpires emotionally between this husband and wife (Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman). Kidman is on-screen only a fraction as long as Cruise, but that doesn’t prevent her from being equally important and even present in the ongoing action, especially since every other woman in the movie is a doppelganger for her. Kubrick’s grace in fashioning such subtle rhymes marks this movie as a masterpiece.