An “En movimiento” column for Caimán Cuadernos de Cine, written in July 2014 for their October 2014 issue. — J.R.

12 June (Chicago): As preparation for serving as a “mentor” to student film critics at the Edinburgh Film Festival, I watch online a film they’re assigned to write about, Adilkhan Yerzhanov’s The Owners from Kazakhstan. This is quite a revelation — at least for me, if not, as I later discover, for most of the students. Three city siblings arrive in the county to claim the ramshackle hut they’ve inherited from their deceased mother, and the tragicomic misadventures and forms of corruption that they encounter oscillate between grim realism, absurdist genre parody, and dreamlike surrealism, culminating in a doom-ridden yet festive dance in which both victims and victimizers participate. Unlike the hyperbolic violence that brutalizes the characters of Jia Zhange’s A Touch of Sin by reducing their humanity, Yerzhanov’s use of genre staples actually expands his expressive and emotional palette without foreshortening our sense of the people involved.

21 & 23 June (Edinburgh): The two high points of my six days here are two very different masterpieces from the first Iranian New Wave, Ebrahim Golestan’s Brick and Mirror (1965) and Parviz Kimiavi’s The Mongols (1973). I’ve seen them both before, yet their scarcity in contemporary film culture remains unconscionable. Golestan, still robust and articulate at age 92, attends his own screening, but Kimiavi can’t come due to a family illness. Both films offer profound critiques of class privilege and cultural differences informed by a stylistic sophistication fully conversant with the European New Waves of the period, but there their similarities end. Golestan’s offers a vibrant glimpse of prerevolutionary Tehran and Kimiavi’s — the first Iranian film I ever saw, in London in the mid-1970s — originally struck me as Godardian (especially for its hilarious quotation of an Anna Karina song), but today it seems ideologically (and in some ways even formally) in advance of 60s and 70s Godard. Both films cry out to be commercially available on DVD.

24 June (Paris): Before I unpack, I rush off to see Godard’s Adieu au langage a few blocks from my hotel (something I’ll do again, at another cinema, almost two weeks later, when I revisit Paris), and, even without being able to follow much of the dialogue, feel that I’m experiencing the real possibilities of 3-D for the first time.

1 July (Bologna): The supreme event at the 28th edition of Il Cinema Ritrovato: an outdoor screening of a 35mm print of Eric von Stroheim’s 1925 The Merry Widow at the Piazza Maggiore, accompanied by a full symphony orchestra performing an original score by Dutch composer Maud Nelissen. [Go to https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mFP-Y77AFuo for a live-action excerpt, recorded elsewhere.] Earlier today, in the same Piazza, being interviewed by Czech filmmaker Lucie Králová for a documentary about film heritage, I’m asked how I might convince young people to see a silent film, and I reply, “By saying that Stroheim knows more about people than Spielberg does — and more than we do.”

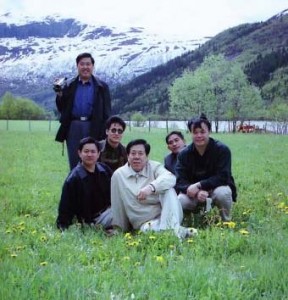

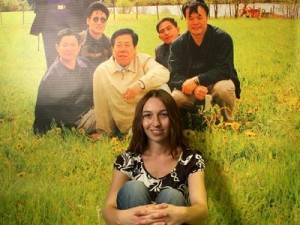

13 July (Chicago): Before returning to Prague from Bologna, Lucie Králová left a DVD of her 2007 documentary Lost Holiday, a Karlovy Vary prizewinner, for me at my hotel, and I finally get around to watching it today at home. The film’s point of departure seems almost as absurdist as the plot of The Owners: A Czech tourist in Sweden finds a suitcase in a dumpster containing 22 rolls of undeveloped film. The negatives yield 756 snapshots of six unknown Chinese tourists visiting various sites in Scandinavia and Germany, and Králová and her crew undertake the impossible challenge of identifying these tourists so that the snapshots might be returned. Years of fruitless detective work later — during which an exhibit of the photos is mounted in Prague, countless trips are made to many of the sites where the pictures were taken and to various lost-and-found agencies and police departments, and attempts are made to enlist the help of mainland Chinese television — the latter initiative finally bears fruit. A Chinese news program broadcasts many of the photos to roughly 300,000,000 viewers. The six tourists, all government officials, are identified, and Králová is flown to China to meet four of them. Best of all, the latter part of her documentary consists of the story as it’s being resumed and celebrated on the Chinese news. Not a great film, but an intriguing exercise in global interactivity.