If memory serves, this essay, which first appeared in the Winter 1985/86 issue of Sight and Sound, and was later reprinted in Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (1995), took me at least a year to write — and maybe even longer than that — because of all the research it required. I’ve recently revised the title slightly from “GERTRUD as Nonnarrative” to “Gertrud as Nonnarrative” because my basic argument concerns the character Gertrud rather than the film as a whole. — J.R.

There are narrative and nonnarrative ways of summing up a life or conjuring a work of art, but when it comes to analyzing life or art in dramatic terms, it is usually the narrative method that wins hands down. Our news, fiction, and daily conversations all tend to take a story form, and our reflexes define that form as consecutive and causal — a chain of events moving in the direction of an inquiry, the solution of a riddle. Faced with a succession of film frames, our desire to impose a narrative is usually so strong that only the most ruthless and delicate of strategies can allow us to perceive anything else.

Carl Dreyer allows us to perceive something else, but never without a battle. Read more

As far as I know or can remember, the credits of only two features have credits that are sung offscreen — Pasolini’s The Hawks and the Sparrows (1966) and Preminger’s Skidoo (1968).

Pasolini’s credits come at the beginning of his feature, Preminger’s at the end of his. Pasolini’s credits are much wittier than Preminger’s.

Rather than conclude that it’s only coincidental that these two films appeared only two years apart, I’m more partial to the possibility that Preminger and/or his writers saw Pasolini’s film and then decided to have its own credits sung. But it’s also worth noting that the mid-1960s was an unusually free and reckless period when the frivolous notion of setting credits in the form of sung lyrics would have been especially feasible. [12/15/2023] Read more

Originally posted in June 2009. — J.R.

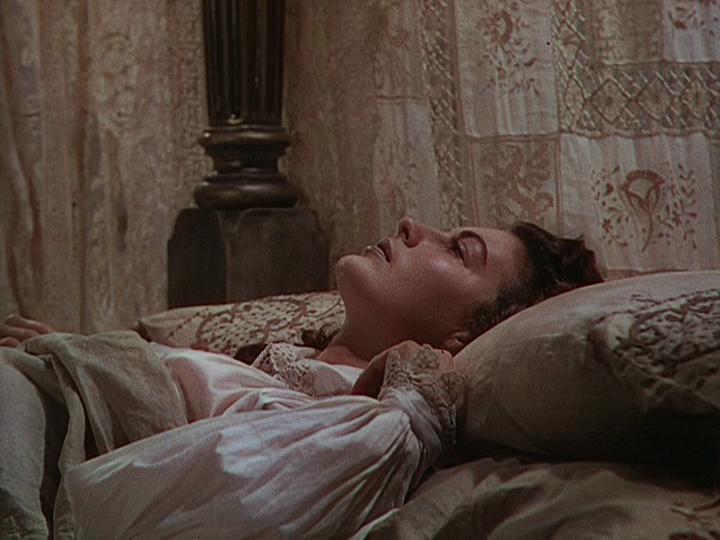

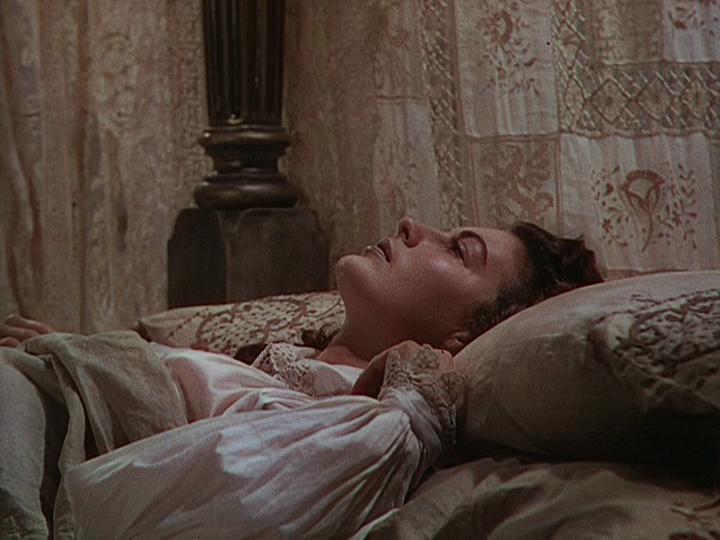

Reseeing an old favorite, Albert Lewin’s delirious Pandora and the Flying Dutchman (1951), towards the end of my penultimate day at Il Cinema Ritrovato, I’m struck once again by how its lengthy, climactic period flashback appears to replicate, anticipate, or at least closely parallel, visually as well as thematically, the murder of Desdemona by Othello in Welles’ Othello, made at almost precisely the same time. Could Lewin have seen the Welles film, or is the resemblance merely coincidental? Even if I had all the precise production information for both films, it would probably be impossible to figure out. [7/3/09]

Read more

Read more

Originally posted in 2010. — J.R.

The first still above comes from writer-director Yves Hanchar’s Sans rancune!, the second from cowriter Sophie Hiet’s and director-cowriter Julie Lopes-Curval’s Mêres et filles, also known as La cuisine and Hidden Diary. Both of these highly involving 2009 features about parents and personal legacies were shown at the French Film Festival held in Richmond, Virginia last month — a sort of pedagogical as well as cultural event presented by Virginia Commonwealth University and the University of Richmond that took place over four days (March 25-28), and where I was privileged and delighted to be a guest.

These two films certainly weren’t the only interesting things I saw at the festival. (Among the more notable items were Philippe Lioet’s touching and beautifully acted Welcome, a story about the growing bond between a Calais swimming instructor and a Kurdish teenager trying to reach a girlfriend in England illegally by swimming across the English channel — a very popular film in France that was nominated for ten Césars last year but sadly won none of them; a very eclectic essay film about motorcycle racing, kids, and movies by Pierre-William Glenn, the remarkable cinematographer who shot both Truffaut’s Day for Night and Rivette’s Out 1; and, strangest of all, Le train oú ça va…, an “intimiste” and domestic 3-D short by Jeanne Guillot, whose masters thesis for La Fémis, arguing that 3-D films need not be spectacular, was translated into English and posted on the festival’s website.) Read more