From the Chicago Reader (April 16, 1993). — J.R.

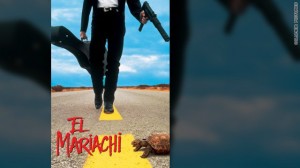

EL MARIACHI

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Robert Rodriguez

With Carlos Gallardo, Consuelo Gomez, Peter Marquardt, Jaime De Hoyos, and Reinol Martinez.

I was several weeks late catching up with El mariachi, a fine little action picture in Spanish that’s been playing at the Water Tower (and opens this week at the Biograph and Bricktown Square). Judging from all the reviews and press stories I read beforehand, an essential part of the movie’s meaning — almost treated as if it were part of the plot — is that its 24-year-old writer-director, Robert Rodriguez, made it for $7,000 and, now a client of Hollywood’s International Creative Management agency, has a two-year contract with Columbia Pictures, the movie’s distributor, that includes plans to shoot a $6 million English-language remake. Much less important, it would seem, is the fate of the movie’s title hero (played by Carlos Gallardo, also Rodriguez’s coproducer). All he ever wanted, “el mariachi” makes clear, is to be a folk musician like his ancestors, though he loses his guitar, the use of one hand, his music, his girlfriend, and possibly even his soul in the process of saving his skin, which entails becoming a successful killer and appropriating the Anglo villain’s weapons. Still less relevant, it would appear, is the movie’s ironic suggestion that Rodriguez’s fate and the mariachi’s may be one and the same.

Rodriguez’s inspirational success story isn’t supposed to give anything away to the audience or ruin its enjoyment. We aren’t supposed to think that doing a $6 million remake of El mariachi in English for the gringos — or having the original shown in upscale neighborhoods — is any sort of humiliation or defeat. On the contrary, we’re expected to conclude that this is the ultimate victory, the only possible thing a poor Latino filmmaker can or should aspire to. (Why should he want to address other poor Latinos instead of us, who matter so much more than they do?) The bitter tale of the mariachi’s survival comments directly on the movie’s theme, but this is apparently felt to be extraneous (it isn’t about us, except negatively) and has been omitted from the reviews I’ve seen. Virtually all that one reads about is the movie’s deft handling of tried-and-true genre conventions, which implies that what it has to say is either nothing at all (the preferred scenario) or so familiar and hackneyed it isn’t worth talking about.

I’ll admit that the tale of disillusionment and lost innocence El mariachi recounts is not exactly a bolt from the blue; take away the ethnic trappings and it even bears some passing resemblance to the jaundiced conclusion of Unforgiven, which just won the Oscar for last year’s best picture. But that it can also — even primarily — be read as a satirical allegory of Rodriguez’s own situation as an independent, no-budget third-world filmmaker seems to have escaped most people’s notice.

Check out the built-in ironies of Rodriguez’s story, even apart from whatever his conscious intentions might have been. To raise funds for the movie, he booked himself into a research hospital two summers ago, allowing his body to be an experimental laboratory for a month while watching movies on video and writing his script. This stint as a lab rat, which got him almost half his budget, is generally regarded as an extreme form of debasement, while his two-year contract with Columbia is defined as the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. But it seems to me that Rodriguez’s current status in the film industry could be described as that of a better paid lab rat with greater opportunities for exploitation and self-abnegation.

Consider too that the movie’s Anglo villain — defined by his wealth and his practice of striking matches to light his cigarettes across his male employees’ faces — spends most of his time lounging in and around a swimming pool. He sits and receives drinks and a manicure from a bimbo in a bikini, just like an old-style Hollywood producer. By contrast, the hero, hoping merely to subsist on modest tips in bars like his father and grandfather, soon finds that electric pianos with their built-in, mechanical-sounding rhythm sections and dehumanized Muzak arrangements have virtually supplanted his folk art, rendering it obsolete. All things considered, laying an electric piano on a mariachi is not unlike bestowing a $6 million movie in English on Rodriguez — except that we’re supposed to frown on the former as vulgar and reductive and heartily approve of the latter as hip and progressive.

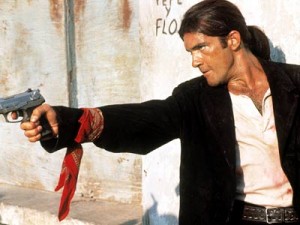

The movie begins not with the folk musician but with his doppelganger, a hit man named Azul (Reinol Martinez) who’s in jail in Coahuila, Mexico. He receives a phone call from Mocho (Peter Marquardt), his Anglo boss, who promises to pay Azul the money he owes him; in the meantime Mocho has dispatched three goons to knock Azul off in his cell. But Azul has already bribed a policewoman to arm him to the teeth, and he calls Mocho back to let him hear the sound of his henchmen being blown away. He then packs his weapons into a guitar case and splits.

The musician turns up on foot in a nearby border town only after the credits come on. Carrying a guitar case with a guitar inside, he’s dressed in black, just like Azul, as he makes the rounds of bars looking for work. Briefly narrating offscreen, he compares his own leisurely pace with that of a turtle we see crossing his path. Speed, in fact, is one of the major ways Rodriguez inflects his own style as a director — either comically speeding up the action or dreamily slowing it down. It’s the perfect strategy for a filmmaker working with limited means — a poor man’s stylistics — but it also has something to do with what his story is about.

Once Mocho orders his other goons to kill the man in black with the guitar case, and both the hit man and the musician are in danger, Rodriguez often distinguishes between them on the basis of speed. The very idea of the hit man inspires frenetic behavior on the part of a hotel clerk ordered by Mocho to report any sighting of Azul, while the musician has a recurring dream in slow motion of a little boy bouncing a rubber ball that turns into a human head. (Each time he has this dream, he wakes to a pit bull breathing in his face, a lazy animal whose laid-back qualities seem to be associated with his own.) More generally, the musician, who moves around on foot, is associated with an older and more traditional Mexican life-style that’s virtually equated with slowness and a feudal economy, while the electric pianos replacing him — one is demonstrated for us in frantic fast motion — and the gangsters with vehicles chasing him are both clearly emblems of Yankee capitalist speed and automation.

Chased by the four armed men dispatched by Mocho, the musician first uses his guitar case as a weapon, then depends on his wits; finally and briefly he appropriates one of their tommy guns. After killing all four men, he drops the gun on the pavement and returns to the second bar where he’s been trying unsuccessfully to get hired as a mariachi. Domino (Consuelo Gomez) — the feisty woman who runs the bar, a sometime girlfriend of Mocho — starts to phone Mocho, then changes her mind and lets the musician hide out in her apartment upstairs (“Watch out for my pit bull”). Later, while he’s taking a bath in her tub, she threatens him by holding a knife to his throat and demanding that he prove his identity by playing the guitar. He responds by improvising a witty song about his predicament (“I’ve been caught with my pants down and there may be a castration . . . “), a form of bricolage, working with whatever happens to be available, that suggests another parallel with Rodriguez’s working methods.

The important thing to keep in mind is that the musician continues to avoid carrying weapons and driving a vehicle until the gravity of the situation forces him to do both. By the end he’s lost everything he cares about except his life, though he has a motorcycle, the pit bull, a knife, and several guns: “With my weapons I’m prepared.” Will Rodriguez’s technological arsenal and salary at Columbia make up for the loss of his artisanal relationship with his art and his cultural-political relationship with his audience — not to mention the urgency of his message? We’ll see.