From Film Quarterly, March 2007, vol. 60, no. 3; reprinted in Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia. Obviously some of this is out of date by now. — J.R.

There’s a part of me that understands perfectly why a

minimalist like Jim Jarmusch and a 19th century figure like

Raul Ruiz won’t have anything to do with email. “You can’t

smell email,” Ruiz once said to me, to explain part of the

reason for his distaste. But I find it tougher to feel

nostalgic about film criticism before the Internet, because

even though you could smell it, the choices of what you

could lay your hands on outside a few well-stocked

university libraries were fairly limited. Similarly, the

choices of what films you could see outside a few cities

like New York and Paris before DVDs was pretty narrow, and

possibly even more haphazard than what you could read about

them.

These two developments shouldn’t be considered in

isolation from one another. The growth of film writing on

the web —- by which I mean stand-alone sites, print-magazine

sites, chatgroups, and blogs —- has proceeded in tandem with

other communal links involving film culture that to my mind

are far more important than the decline in the theatrical

distribution of art films and independent films, so I’ll be

periodically discussing those links here. Read more

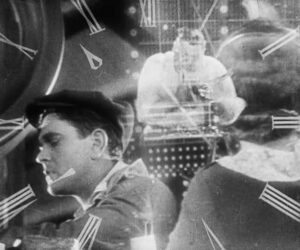

Paul Fejos’s exquisite, poetic 1928 masterpiece about love and estrangement in the big city deserves to be ranked with F.W. Murnau’s Sunrise and King Vidor’s The Crowd from the same period, though it’s not nearly as well-known. Equally neglected is Fejos himself, a peripatetic Hungarian who made striking films in Hungary, Hollywood, Austria, and France in the late silent and early sound era before becoming an anthropologist — and making a few ethnographic films that are even harder to find. Lonesome, which has some dialogue, begins with a dazzling evocation, using superimpositions and diptychs, of the hero and heroine, who haven’t yet met, as they wake and pursue their morning work routines. They meet at Coney Island that afternoon, lose track of each other in a crowd, then are reunited back in the city in a surprising diptychlike scene. Fejos was already interested in ethnographic archetypes when he made this picture, which makes city life seem like a labyrinth in a fairy tale — as intricate and inscrutable, but also as enchanted. 69 min. The opening event of the weekend symposium “Cinema as Vernacular Modernism”; a 35-millimeter print will be screened. Univ. of Chicago Doc Films, 1212 E. 59th St., Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 4, 2005). — J.R.

Chain

*** (A must-see)

Directed and Written by Jem Cohen

With Miho Nikaido and Mira Billotte

Chain, the first solo feature by film and video artist Jem Cohen, is a strange mix of documentary and fiction about malls and similar commercial spaces. It’s meditative rather than action packed, and the creepiness it exposes has as much to do with absence as presence. But it deserves more attention than the single local screening it’s getting at Columbia College. I suspect it’s not getting more because it was partly funded by European television, because distributors never know how to package films that merge documentary and fiction, and because it belongs to the netherworld between film and art (it’s playing in conjunction with the Museum of Contemporary Photography’s exhibition “Manufactured Self”). It hasn’t even made the art-house circuit, which is a loss: it’s highly ambitious, has plenty to say, and is far from inaccessible.

Chain was shot in 16-millimeter over six years in hundreds of malls around the world — Atlanta, Dallas, Orlando, Berlin, Paris, Warsaw, Melbourne. That it’s impossible to tell the malls’ locations is part of the point. “I began the project,” says Cohen in his press notes, “by deciding to focus on the corporate and commercial landscapes that I had previously ‘framed out’ in my filmmaking, and to try to understand how these places were affecting the people within them. Read more

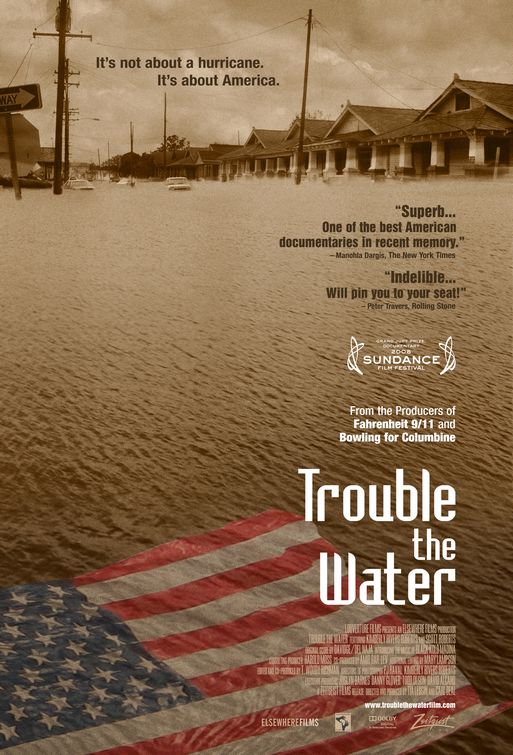

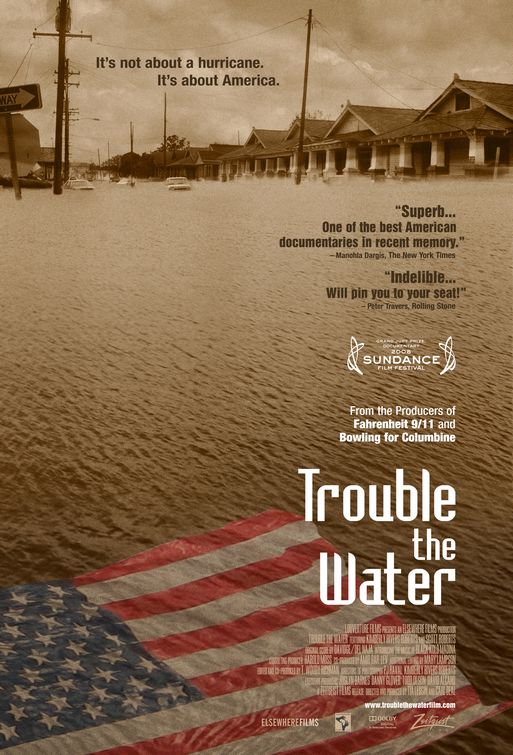

Here’s the unedited version of a review I wrote for In These Times, published in their September 3, 2008 issue. — J.R.

I can’t quite follow all of the offscreen sound bites preceding the main title of Tia Lessen and Carl Deal’s Trouble the Water. But it’s clear from the media voices I can transcribe that they concisely present this documentary’s agenda — at the same time we see the intertitle “September 14th 2005/Central Louisiana” appear onscreen and then get our first glimpses of some of the people who’ll shortly become this documentary’s central characters, seated around a picnic table.

Two of the offscreen voices come from George W. Bush; the others all sound like they come from newscasters or interviewees:

1. Read more

This essay was written in late November 2010 for The Common Review, whose editor commissioned it, but was subsequently and recently withdrawn from that magazine once it became clear that the editor wasn’t giving me any straight or candid answers about whether or when he would publish it. Which is why I’m publishing it here. I’ve only updated it slightly to incorporate the recent distressing news about the government’s sentencing of Jafar Panahi. And more recently, thanks to Danny Postel, this article has been reposted here, at Tehran Bureau. P.S.: This essay is included in the much-expanded second editition of Abbas Kiarostami (2019), a book I coauthored with Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa.– J.R.

To what extent does Abbas Kiarostami, Iran’s best known and most celebrated filmmaker, still belong to Iran, and to what extent does he now belong to the world? Insofar as the first sixteen of his seventeen features have been shot in Iran –- only Certified Copy, filmed in Italy, which premiered in Cannes last May, qualifies as a feature shot in exile –- he might be said to “belong” in some fashion to his native country. But the last of his features to date to have opened commercially in Iran was his tenth, Taste of Cherry (1997), and one wouldn’t expect this situation to change anytime in the near future. Read more

I no longer recall where this 2008 review was written for. — J.R.

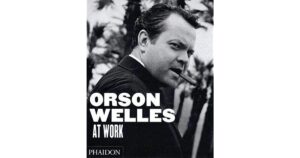

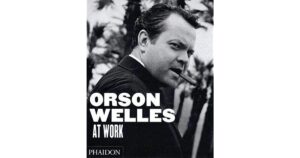

ORSON WELLES AT WORK by Jean-Pierre Berthomé and François Thomas. London/New York: Phaidon Press, 2008. 320 pp.

Considering how much popular currency is enjoyed by works about Orson Welles that are poorly researched, possibly because they respond so dutifully to existing attitudes and mythologies about the man — most notably, David Thomson’s slipshod biography Rosebud and Michael Epstein and Thomas Lennon’s Oscar-nominated but fanciful documentary The Battle Over Citizen Kane (both 1996) — a reliable book about his filmmaking that doesn’t stoop to special pleading is always welcome. This one, originally published in French a couple of years ago — in an ongoing series of beautifully and copiously illustrated coffee-table books that has already yielded Bill Krohn’s indispensable Hitchcock at Work — is special not just for the amount of fresh information it offers. It’s also invaluable because of the unusual perspectives its two authors bring to their subject.

Jean-Francois Berthomé, author of a definitive book on Jacques Demy, is also an expert on movie set design, the subject of another of his books. François Thomas, an Alain Resnais specialist, once wrote a dissertation on Welles’s sound work (in film, radio, TV, and theatre) that was over a thousand pages long. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 31, 2003). — J.R.

Sylvia

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Christine Jeffs

Written by John Brownlow

With Gwyneth Paltrow, Daniel Craig, Jared Harris, Amira Casar, Andrew Havill, Lucy Davenport, Blythe Danner, and Michael Gambon.

In the Mirror of Maya Deren

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Martina Kudlacek

Greasing the bodies of adulterers

Like Hiroshima ash and eating in.

The sin. The sin.

— Sylvia Plath, “Fever 103 °“

In film, I can make the world dance.

— Maya Deren

In college it always seemed like the guys who were poets got more girls than the prose writers. The assumption was that poets had all the romance and sensuality associated with their medium working for them. Poetry, after all, isn’t just a block of printed material; it’s an activity, and one that can turn people on sexually as well as spiritually.

In cultures such as those of Russia and Iran sexual and spiritual qualities tend to run neck and neck: the great Persian poet Forough Farrokhzad (1935-’67), a fan of Sylvia Plath, retains a mythic allure that combines the auras of Joan of Arc, Billie Holiday, and Marilyn Monroe. And an erotic charge is one of the first things that Sylvia, a biopic about Sylvia Plath (1932-’63), gets right. Read more

The blighted relationships explored by a Prague psychologist with marital troubles of her own (Jana Janekova, excellent) are the focus of Vera Chytilova’s 2006 Czech feature, her best in many years. With its aggressively mobile camera and abrupt editing, the movie seems to lurch from one miniplot to the next as if in a punch-drunk trance. Like much of Chytilova’s best work (Daisies, The Apple Game), it sometimes verges on hysteria, but it’s clearly enhanced by the experience of screenwriter Katrina Irmanovova, a therapist herself. And her fictional patients evoke the letter writers of Nathanael West’s novel Miss Lonelyhearts in their cumulative misery, suggesting some poetic yet plausible version of the modern world. In Czech with subtitles. 108 min. (JR) Read more

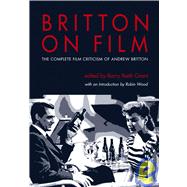

From Film Comment (March-April 2009). — J.R.

Britton on Film

The Complete Film Criticism of Andrew Britton

Wayne State University Press, $39.95

Even if you don’t agree with the claim in Robin Wood’s Introduction that Britton (1952-1994) “was, and remains, quite simply, the greatest film critic in the English language,” this hefty collection edited by Barry Keith Grant, 534 large-format pages long, certainly proves that Wood’s cantankerous Marxist disciple, who published mainly in Movie (U.K.) and CineAction (Canada), was a formidable figure. To my taste, the two best demonstrations of his intellectual and ethical strength are his separately published Katherine Hepburn: The 30s and After (1984), the best book-length study of a film actor that I know (misleadingly retitled Katherine Hepburn: Star as Feminist in its U.S. edition), and his passionate defense of Mandingo in Movie (1976), which single-handedly established that film’s importance amidst a chorus of jeers. And even if the absence of the first study from this book already makes its subtitle not quite accurate, the full range of Britton as both a polemicist and an analyst of everything from Detour to Madame de… to Jaws to Tout va bien is amply on display here.

One limiting factor here is the amount of space devoted to refuting such academic touchstones as Screen in the 70s and The Classical Hollywood Cinema — engaging with labyrinthine debates that seem less consequential now, at least to nonacademics like myself, than they did at the time. Read more

This appeared in the May 1, 2008 issue of the Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Last Year at Marienbad ****

DIRECTED BY ALAIN RESNAIS

WRITTEN BY ALAIN ROBBE-GRILLET

WITH GIORGIO ALBERTAZZI, DELPHINE SEYRIG, AND SACHA PITOEFF

It’s too bad Last Year at Marienbad was the most fashionable art-house movie of 1961-’62, because as a result it’s been maligned and misunderstood ever since. The chic allure of Alain Resnais’ second feature — a maddening, scintillating puzzle set in glitzy surroundings — produced a backlash, and one reason its defenders and detractors tend to be equally misguided is that both respond to the controversy rather than to the film itself.

“I am now quite prepared to claim that Marienbad is the greatest film ever made, and to pity those who cannot see this,” proclaimed one French critic, even as others ridiculed what they perceived as the film’s pretentious solemnity — overlooking or missing its playful, if poker-faced, use of parody as well as its outright scariness. Dwight Macdonald, who admitted to seeing the movie three times in a week, confessed in Esquire that it made him feel like a dog in one of Pavlov’s experiments. In the Village Voice, on the other hand, Jonas Mekas claimed that “the film begins and ends in the brain of Alain Robbe-Grillet, who wrote the script” and added, “Its forced intellectualism is sick.” Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 7, 2004). — J.R.

Ford Transit

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Hany Abu-Assad

Written by Abu-Assad and Bero Beyer.

Super Size Me

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed and written by Morgan Spurlock.

What do we expect from documentaries? Do we seek to be informed by them or merely entertained? If it’s the former, do we expect some guidance about how to process the information?

The documentaries I’ve seen lately have made me ponder these questions. For example, last week at the Buenos Aires Festival of Independent Film I saw a fascinating Palestinian feature called Ford Transit (showing twice this week at Facets Cinematheque) that freely mixes fiction and nonfiction as if they were alternate routes to the same goal. I also attended the world premiere of a more conventional documentary, The Take, which was made for Canadian TV and may never screen here. Finally, there’s Super Size Me (which opens at the Landmark this week), a film that has been getting considerable attention since it premiered at the Sundance festival last January.

Let’s start with The Take, which was directed by Avi Lewis and written by Naomi Klein, who’s a columnist for the Nation and the Guardian and author of the international best seller No Logo, a journalistic account of the worldwide antiglobalization movement. Read more

I was interviewed by Estado de Minas, the largest newspaper in Belo Horizonte, Brazil, shortly before and in connection with my plans to teach a ten-hour course on Charlie Chaplin there in mid-August 2012. (They ran some of my comments on criticism but omitted what I had to say about Chaplin.) Here are their questions and my responses….The first photo below shows Chaplin in a London film studio with Cy Endfield (on the left). — J.R.

1. Questions about Chaplin:

Why do we still love Charlie Chaplin? What makes him so relevant in 2012?

These are questions that I hope my course will help to answer. Right now, one of my main reasons for wishing to teach this course is that I don’t know the answers to these questions.

Why do you think Chaplin must be reintroduced to contemporary filmgoers? Isn’t he universally recognized and understood enough already?

It would be presumptuous of me to speak about whether or not Chaplin is adequately recognized today in Brazil —or, for that matter, in any country that I haven’t visited and/or whose language I neither speak nor read. But to make a generalization based on my experience, I would say that Chaplin tends to be universally recognized today as a great performer, but very widely unrecognized, undervalued, and misunderstood as a filmmaker. Read more

Adapted and condensed from “Comparaisons à Cannes,” translated by Jean-Luc Mengus, Trafic no. 19, été 1996. -– J.R.

In his introduction to Understanding Media, Marshall McLuhan

records the consternation of one of his editors that “seventy-five

per cent of your material is new. A successful book cannot venture

to be more than ten per cent new.” From the vantage point of this year’s

Cannes Festival, a compulsion to contextualize everything new in

relation to something familiar reveals a comparable problem. Indeed, the

kind of movie pitch parodied at the beginning of Altman’s The Player,

in which every project becomes some version of one or two previous

hits — “The Graduate, Part 2,” “The Manchurian Candidate meets

Ghost” — has by now become a kind of journalistic shorthand for the

critic eager to make the film fully accessible once it’s released. This

necessity of establishing old references in relation to new ideas is above

all an indication of how thoroughly the priorities of the film business

have infiltrated film criticism.

As useful as this practice is, it often functions as a kind of nervous

tic. For the writer or speaker too lazy to perform the less alluring task

of description, it poses a constant temptation — a means of short-

circuiting the critical process through a kind of magic or alchemy that

suddenly makes the invisible visible. Read more

It seems that class anxiety has become Woody Allen’s key and obsessive theme ever since his movies started to become “serious”, and it’s usually around in some form even in the purer comedies. Indeed, almost all of the cultural concerns of his work wind up having something to do with class issues — almost as if Allen really believed the crazy American myth that espresso and wealth are inextricably interconnected. The main fantasy about expatriate American bohemians in Midnight in Paris isn’t really about art; it’s about Hemingway or somebody like that stepping into a cab and not worrying about having to pay the driver (which F. Scott Fitzgerald or T.S. Eliot can always take care of), and if Gertrude Stein likes your novel, the bottom line is social acceptance and approval, not artistic license or accomplishment.

From this point of view, Blue Jasmine represents Allen’s coming-out film, by virtue of placing his class anxieties front and center, not through embarking on any themes that are significantly new for him. The vague use of A Streetcar Named Desire (movie and play) as a loose model, with Cate Blanchett serving as a sort of Yankee Blanche DuBois, parallels the vague uses of A Place in the Sun and An American Tragedy in Match Point. Read more

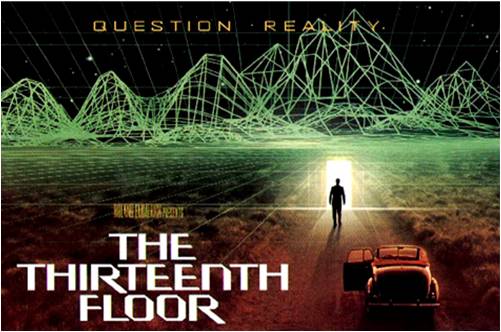

From the June 4, 1999 Chicago Reader. A lot of the material here subsequently turned up in my book Movie Wars. — J.R.

The Thirteenth Floor

Rating * Has redeeming facet

Directed by Josef Rusnak

Written by Rusnak and Ravel Centeno-Rodriguez

With Armin Mueller-Stahl, Craig Bierko, Gretchen Mol, Vincent D’Onofrio, Dennis Haysbert, and Steven Schub.

“I think, therefore I am,” reads the opening epigraph of The Thirteenth Floor, followed by the quotation’s source, “Descartes (1596-1650).” It’s an especially pompous beginning for a movie whose characters barely think, much less exist, but not too surprising given the metaphysical claims and pronouncements that usually inform virtual-reality thrillers.

This is the fourth such thriller I’ve seen in as many weeks, and if any thought at all can be deemed the source of these pictures cropping up one after the other — with the exception of David Cronenberg’s eXistenZ, a film with more than generic commercial kicks on its mind — it might be an especially low estimation of what an audience is looking for at the movies. The assumed desire might be expressed in infantile and emotional terms: “I don’t like the world, take it away.” In other words, for filmmakers stumped by the puzzle of how to address an audience assumed to be interested only in escaping without reminding them of what they’re supposed to be escaping from, virtual-reality thrillers seem made to order. Read more