From the Chicago Reader (September 23, 1994). — J.R.

QUIZ SHOW ***

(A must-see)

Directed by Robert Redford

Written by Paul Attanasio

With Rob Morrow, Ralph Fiennes, John Turturro, David Paymer, Christopher McDonald, Elizabeth Wilson, and Paul Scofield.

Behind the opening and closing credits of Quiz Show we hear two different pop versions of “Mack the Knife” — Bobby Darin’s bright, Lyle Lovett’s funereal — perhaps an indication that director Robert Redford has something faintly Brechtian in mind. If so, probably the most relevant Brecht passage is the exchange that concludes the 12th scene of Galileo, when Andrea, the son of Galileo’s housekeeper, quotes the maxim “Unhappy is the land that breeds no hero.” Galileo replies, “No, Andrea: ‘Unhappy is the land that needs a hero.'”

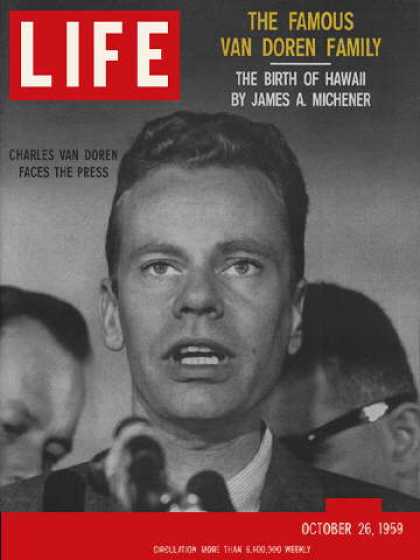

On the other hand, this is Robert Redford we’re talking about, who’s been a hero in this unhappy land for the past three decades, not someone who’s ever been known to seriously rock any boats. A better indication of what makes Quiz Show so interesting, suggestive, and fruitful (if not Brechtian) is the showroom spiel for a glittering Chrysler 300 given to the movie’s hero, congressional investigator Richard N. Goodwin, shown out shopping just before the opening credits. After all, one of the best ways to learn about any period is to enter its dreams and fantasies, and the Chrysler 300 was as much a part of the reveries of the late 50s as was the hero worship of Charles Van Doren, star contestant on the quiz show Twenty-One. More to the point, the Chrysler 300 is part of Goodwin’s fantasies — a man for whom class and social status and even hero worship mean almost as much as telling the truth.

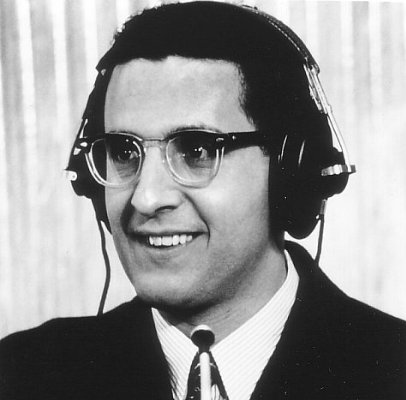

In a way, the best thing that can be said about Quiz Show is that it’s a good Hollywood-liberal 50s movie, a movie in which a noble man bears the burden of a complex ambivalence about his mission — exposing the quiz show frauds, especially difficult in the case of Van Doren — an ambivalence everyone in the audience can be expected to share. Goodwin, a man who stands in the middle, is Jewish — as are the less appealing Herb Stempel, an obsessive working-class quiz show winner who exposes Van Doren as a fraud, and the cynical producer Dan Enright, who helps to perpetuate the fraud. But Goodwin, a well-groomed graduate of Harvard Law School (which he attended on a scholarship) who appreciates the “finer” things of life, is more in Van Doren’s social orbit than Stempel’s. If Quiz Show were truly Brechtian, it might have started with Van Doren in that Chrysler showroom, introducing not only a cynical complicity with but some irony about this falsely anointed national hero. Instead it sides with the congressional investigator who regretfully helps to bring him down.

Whatever Redford’s qualms about falsely anointing heroes, certain aspects of Goodwin’s role in the proceedings are exaggerated, distorted, and romanticized. The most complete account I know of, though it’s far from the best known, is Prime-Time and Misdemeanors: Investigating the 1950s T.V. Quiz Scandal (1992), coauthored by Tim Yohn and former assistant district attorney Joseph Stone — a key figure in uncovering the scandal, whom Goodwin himself called “diligent, experienced, [and] incorruptible.” Significantly, Goodwin doesn’t even appear in the book’s chronicle of events until its final third, and Stone tactfully implies more than once that Goodwin had plenty of ambition and star-struck aspirations of his own. The movie neither mentions nor depicts Stone, who recently called it a “tawdry hoax” because of its simplifications and abridgements. (Two more popular and condensed accounts of the scandal — more readable but less informative — are the third chapter of Goodwin’s 1988 Remembering America: A Voice From the Sixties, the only source Quiz Show credits, and the 43rd chapter of David Halberstam’s 1993 The Fifties.)

When the quiz show scandals broke in 1959, I was at boarding school and didn’t have access to a TV, but I vividly recall the intense family ritual in the mid-50s of watching The $64,000 Question, The $64,000 Challenge, and Twenty-One. I especially remember the collective thrill when the first contestant on the first of these shows, three months after it premiered, won the top prize of $64,000 on September 13, 1955: the moment after it happened, my brothers and I phoned various friends and relatives to talk about it. And when well-groomed college professor Charles Van Doren toppled Herb Stempel as champion on Twenty-One almost 15 months later, my father seemed to regard this feat as a combined sports victory and triumph for Western civilization. By the time all three shows went off the air, in the fall of 1958, much of this exhilaration had worn off, but the idea of cultural conquest on a grand scale continued to hover over our lives like a pledge, even after the multiple deceptions and lies of these quiz shows were exposed. When John F. Kennedy invited Robert Frost to his inauguration, in early 1961, that promise seemed to have been renewed.

Spurred by this movie, many recent commentators have been saying that the quiz show scandals marked the beginning of a certain loss of American innocence. Goodwin himself explicitly refutes this idea in Remembering America, however: “The intensity of indignation, the extent of public outrage, was testimony to an American innocence of belief strong enough to survive this and graver challenges to come; an innocence that was to quicken the public movements and private rebellions of the sixties until it dissolved in the futilities of Vietnam. For innocence is a strength. . . . The hopeless do not revolt. The cynical do not march.” Goodwin — who went straight from the House subcommittee investigating the quiz shows to Senator John F. Kennedy’s staff in 1959, a path that eventually led to the White House as speechwriter and policymaker and then into associations with Lyndon Johnson and Robert Kennedy — was probably as much a spokesman for that innocence as he was a tool in its dismantlement. Though his stated goal was to expose the networks’ and sponsors’ complicity in fixing the quiz shows rather than destroying the careers of the producers and contestants, he was too much a man on the make not to have a few star-struck ambitions of his own.

Redford and screenwriter Paul Attanasio fully realize this, and so does Rob Morrow, who plays Goodwin with a thick Boston accent that clearly evokes Kennedy. As the film implies, Van Doren on Twenty-One in 1956-’57 was like a first draft of Kennedy, and Goodwin in 1959-’60 was like a second draft; if Kennedy himself in 1961-’63 was the third “draft,” these screen versions of Van Doren and Goodwin represent a fourth. Hope, as they say, springs eternal; as film scholar Tom Gunning pointed out to me, Morrow’s speech patterns also allude to James Stewart’s in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. However much this movie may seek to demystify former illusions, its project, like that of JFK, remains incurably romantic and abjectly in awe of power.

The only clear casting error in the movie is a central one: Ralph Fiennes looks and sounds nothing like Charles Van Doren. Since winning an Oscar for his charismatic Nazi thug in Schindler’s List, this English actor has become one of Hollywood’s fair-haired boys, and I suppose the logic of casting him is that well-groomed Van Doren was one of the 50s fair-haired boys. Like the movie’s fumbling efforts to reproduce the intellectual small talk of the 50s, casting Fiennes is a stab at something the filmmakers are more interested in representing than understanding: what’s missing from his performance is any sense that Van Doren had an inner life beyond his well-tailored public persona (in this respect and others, Morrow does a much better job).

Still, Quiz Show‘s subject is rich with implications, and Redford’s efforts to depict its contours accurately are so vigorous that I find this movie a lot more compelling than any of his other directorial efforts. As a watershed in American media history, standing somewhere between the McCarthy purges (when public confessions were deemed a social necessity) and Watergate (when they weren’t), the scandals arguably put an end to live TV programming. Paradoxically they began like Watergate, with a series of press leaks, and ended like the McCarthy hearings, with a Whittaker Chambers-style confession from Van Doren. (There were also salient differences from the McCarthy period: Chambers’s confession of his former communist activities catapulted him into fame, while Van Doren’s was followed by his disappearance from public life.)

One of the more interesting spins Quiz Show gives this material is to highlight the ethnic conflicts involved in the unveiling of the media deceptions — specifically Stempel’s anger about being forced to take a fall on Twenty-One so that WASP heartthrob Van Doren could win. But unfortunately, though the movie aims to be forthright on this subject, it ultimately confuses ethnic differences with class differences — a common Hollywood failing. Thus Goodwin seems to admire Van Doren because the Connecticut home of his father, the poet Mark Van Doren, is so lush and because he owns a Mercedes. Similarly, Stempel is “Jewish” because he lounges about in his underwear. (Turturro, who’s already played unlikable New York Jews in Mo’ Better Blues, Miller’s Crossing, and Barton Fink, seems to be making a specialty of this kind of part — and he’s getting better at it all the time.)

In his book Goodwin makes it plain that he personally liked Van Doren and disliked Stempel; as he puts it, “Van Doren almost got away. I wanted him to. And his downfall, when it came, was not Stempel’s doing, but the consequence of Van Doren’s own self-destructive stupidity.” The movie shows this friendship evolving out of Van Doren’s invitations to Goodwin, but in fact the evidence suggests Goodwin took most of the social initiatives. On the night before Van Doren’s testimony before the subcommittee, for instance, Goodwin invited him, his wife (a character omitted in the movie), his father, and Joseph Stone to dinner at his home in Georgetown.

In a key sequence designed to challenge Goodwin’s softness on Van Doren, Goodwin’s wife berates him, calling him “the Uncle Tom of the Jews”; she adds, challenging his desire to protect his friend, “The quiz shows without Van Doren is like Hamlet without Hamlet.” Another version of that line turns up in Goodwin’s book as well as Halberstam’s, but the person who originally uttered it was not Goodwin’s wife but Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter — for whom Goodwin worked as a law clerk before investigating the quiz shows. Like Stone and Van Doren’s wife, Frankfurter is not mentioned in the movie, but Goodwin went to him for advice after he was instructed to serve Van Doren with a subpoena and was conscience-stricken about wrecking his friend’s career. (By that time Van Doren had long since exited Twenty-One, but he had a lucrative daily stint on the Today show and a teaching position at Columbia, both of which he lost after testifying.) Frankfurter’s response, as reported in Goodwin’s book, was, “To the public Van Doren is the quiz shows. It would be like playing Hamlet without Hamlet. You’re not pursuing an innocent victim, but a willing participant. The fact others may have done worse doesn’t make him guiltless.”

This is more or less the movie’s position too. But even though Quiz Show is rightly and bracingly explicit about the networks’ and sponsors’ venality, naming names and showing the corruption in action, by giving the Stempel-Van Doren-Goodwin situation the full star treatment, it ends up underplaying the complicity at high levels. As Goodwin pointedly observed, “The networks and sponsors made many millions. The producers made a few million. The contestants made thousands. And all was right with the world.” Typically, the real villains in this movie aren’t the top dogs but the middlemen like Enright, though the movie pretends to argue otherwise.

In short, the quiz show story is no Hamlet, though this movie tries to make it one, with Goodwin and Van Doren both standing in for the uncertain hero. And though TV and Hollywood habitually partake of the same corruptions and deceptions, Quiz Show follows the expedient 50s tactic of using Hollywood machinery to attack the small screen. The process is riveting to watch and fascinating to think about, though the dubious star system that keeps both in place is left unchallenged.