From the June 24, 2005 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

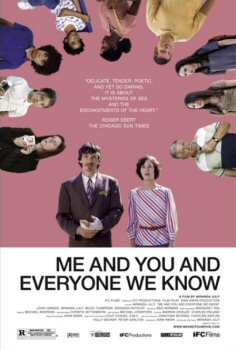

Me and You and Everyone We Know

*** (A must see)

Directed and Written by Miranda July

With John Hawkes, July, Miles Thompson, Brandon Ratcliff, Carlie Westerman, and Natasha Slayton

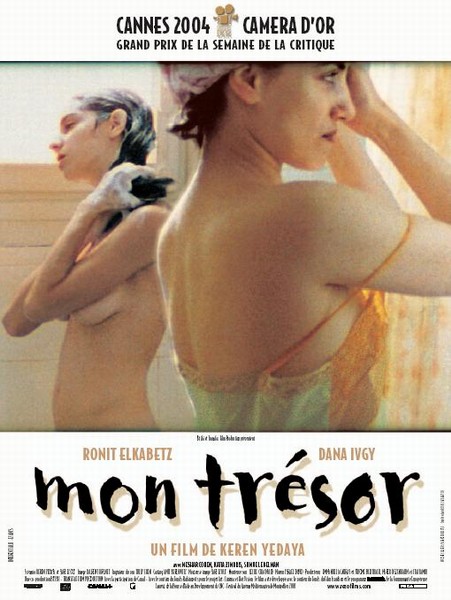

Or

*** (A must see)

Directed by Keren Yedaya

Written by Yedaya and Sari Ezouz

With Dana Ivgi, Ronit Elkabetz, Meshar Cohen, Katia Zinbris, and Shmuel Edelman

Samaritan Girl

no stars (Worthless)

Directed and written by Kim Ki-duk

With Kwak Ji-min, Seo Min-jeong, Lee Eol, Hyun-min Kwon, and Young Oh

“Sex is Confusing” could serve as an alternate title to these three movies, all high-profile film festival prizewinners. The first is an American woman’s debut feature, the second an Israeli woman’s first feature, and the third is Korean director Kim Ki-duk’s tenth.

Miranda July’s account of the inspiration for Me and You and Everyone We Know gives an indication of her wistful comedy’s strengths and limitations. “This movie was inspired by the longing I carried around as a child, longing for the future, for someone to find me, for magic to descend upon my life and transform everything,” she writes in the press packet. “It was also informed by how this longing progressed as I became an adult, slightly more fearful, more contorted, but no less fantastically hopeful.”

July’s main characters, all kids at heart, are a lonely video artist and driver for the elderly (July), a shoe salesman (John Hawkes) recently separated from his wife, and his two sons, ages 7 (Brandon Ratcliff) and 14 (Miles Thompson). The secondary characters include the shoe salesman’s male coworker, a couple of teenage girls, a ten-year-old girl, and a woman who curates at a local art museum. These characters are touching and sympathetic to the extent that they’re lonely, and that’s what most of them are most of the time. The teenage girls, who have each other, are basically viewed as heartless; the same applies to the ten-year-old girl when she’s briefly seen hanging out with other girls. The shoe salesman’s estranged wife, who has a lover, isn’t lonely or childlike — she doesn’t belong to the same world. She also happens to be the only black character, which inflects the isolation of her kids, but one isn’t encouraged to think that her race plays any part in her own separateness.

July’s tender view of these characters borders on the sentimental, especially when it comes to the seven-year-old boy — if only because Ratcliff is a natural and an all but ruthless scene-stealer. Yet the way a couple of these people flee from romantic or sexual intimacy the moment it’s offered suggests that they might be happier living with their fantasies than with the opportunity of fulfilling them.

In the Anyplace, America, of Me and You and Everyone We Know, sexual encounters are arranged via instant messaging. No such middle-class luxuries are in evidence in Keren Yedaya’s Or, set in slummy sections of Tel Aviv, where aging Israeli hooker Ruthie (Ronit Elkabetz) and her resourceful teenage daughter, Or (Dana Ivgi), have to rely on word of mouth or the street.

When in the opening sequence Or collects Ruthie from a hospital and brings her home, it’s apparent that she’s the one in the responsible parental role. Ruthie’s addicted to turning tricks — not so much for the money as for the self-esteem and sense of power she derives from it — and there’s an acute pathos when Or locks her inside their cramped flat before going out to work as a dishwasher. Meanwhile Or’s periodically enjoying some sex of her own with her boyfriend, who lives in the neighborhood. Yet by the film’s end we see she’s well on her way toward becoming a prostitute herself — an outcome that’s made to seem wholly believable, but not explicable in any single or simple way.

Two critics I admire, the Village Voice‘s Jessica Winter and the New York Times‘s Manohla Dargis, view this determinism with some skepticism about its ideological rigidity, and it’s hard not to share their questions. But the script is full of gaps that prevent us from fully understanding either character: we know nothing about Or’s missing father and only a little about Ruthie’s emotional problems, and the giggling complicity between mother and daughter in some scenes hints at shared understandings we can only speculate about. Furthermore, the stubborn detachment of the mise en scene is a lot more ambiguous than anything the plot seems to be implying: Yedaya typically plunks her camera down in a single position for each scene, refusing to budge even when the characters move out of the frame, and one of the effects of this impartiality is to challenge some of our received ideas about the sexuality of both mother and daughter. It’s easy at first to feel scornful of Ruthie’s desire for sex and tolerant of Or’s, but then, once our own biases are put in the foreground by the visual style, we may start to question both positions. And the degree to which the militarism of the Israeli occupation is playing a role in furthering male sexual entitlement, while never directly addressed, seems to be affecting both women at every turn. Insofar as they’re implicitly the spoils of war, this movie seems to be meditating on the whys and hows of the spoiling process — raising more questions than can possibly be answered, and in this sense, at least, far from dogmatic.

As far as I can tell, Samaritan Girl has no questions but only answers up its sleeve. Since I find the last part of this movie unfathomable, however, I may be missing something. The preceding parts are so literal minded, as both puritanical and pornographic illustrations of an obnoxious male fantasy, that they strike me as alternately absurd and hypocritical.

Two teenage girls in Seoul, Yeo-jin (Kwak Ji-min) and Jae-yeong (Seo Min-jeong), go into prostitution, the former pimping for the latter via instant messaging, to raise money for tickets to Europe. As we can see when they bathe each other and kiss in an erotically lit bathhouse, they’re more than just friends, so Yeo-jin becomes distressed when Jae-yeong shows signs of enjoying her work, intimating that she sees herself on a religious mission and becoming interested in her clients, in particular one who’s a pop composer.

Escaping from the cops after turning a trick, Jae-yeong leaps from a high window in her underwear and Yeo-jin carries her to a hospital, where Jae-yeong points to the name and address of the composer in her diary and begs, “Bring him to me — I miss him.” Yeo-jin dutifully looks up the composer, who refuses to come unless Yeo-jin, who’s a virgin, has sex with him first. By the time they arrive at the hospital, Jae-yeong is already dead, a blissful smile on her lips.

With Jae-yeong’s diary as her guide, Yeo-jin proceeds to locate and have sex with Jae-yeong’s former clients, trying to understand her dead friend. (Perversely, she also returns their money and thanks them.) Yeo-jin’s widower father, a cop, finds her doing this, then tracks down the clients himself, murdering one of them and driving another to suicide after humiliating him in front of his family with my favorite idiotic line in the film: “Filthy bastard,” he spits. “You sleep with a girl younger than your daughter. Even dogs don’t do that.”

Then — and here’s where the story completely loses me — he and his daughter spend some idyllic hours in the countryside, discussing Mother Teresa while being put up by a friendly peasant. In the morning he gives her a driving lesson, and she winds up getting their car stuck in the mud.

Kim Ki-duk is a prestigious figure, at least in the West. He’s been praised for such high-minded fare as Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter . . . and Spring (2003), but when Asian specialist Tony Rayns attacked him for his “sexual terrorism” in Film Comment last year it was understandable: The Isle, his 2000 psychodrama, has several scenes of genital self-mutilation. I’d cite Samaritan Girl‘s use of a pop electronic version of an Erik Satie piano piece and the strident, garish acting as further evidence of his taste — though if one wants to be more generous about his intentions, the striking recurrence of ripe autumn foliage in this film could probably also be noted along with Mother Teresa and the mud.