From the Chicago Reader (November 1, 1996). — J.R.

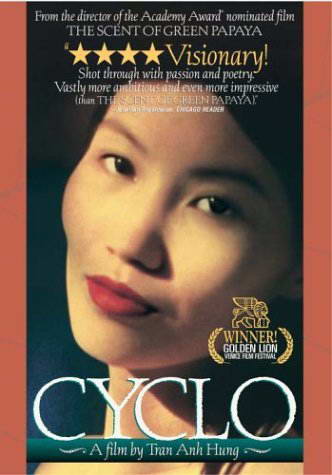

Cyclo

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed and written by Tran Anh Hung

With Le Van Loc, Tony Leung-Chiu Wai, Tran Nu Yen Khe, Nguyen Nhu Quynh, Nguyen Hoang Phuc, and Ngo Vu Quang Hai.

Tran Anh Hung’s first feature, The Scent of Green Papaya, redefined what we mean by “inside” and “outside,” architecturally as well as socially and psychologically. The same could be said about the vastly more ambitious and even more impressive Cyclo, which was shot in Ho Chi Minh City — unlike The Scent of Green Papaya, which was shot in a studio outside Paris — and is set in the present.

The Scent of Green Papaya — the first and so far only Vietnamese film ever nominated for an Academy Award — was inspired by the filmmaker’s memories of his mother and was set in 1951 and 1961. Tran said that his next feature would be based on recollections of his father. This led me to expect another period film, which Cyclo isn’t — but there’s no question that it’s a film about patriarchy. The first and last things the 18-year-old hero (Le Van Loc) says offscreen concern his late father — a pedicab driver who was run over by a truck — and there’s the sense throughout that he’s stuck in an endless cycle of male misery passed from one generation to the next.

Tran was born in Vietnam in 1962 and moved with his family to Paris in 1975, where he’s lived ever since, so he relates to his country of birth as both an insider and an outsider. Similarly, the degree to which French culture and cinema have shaped him can’t be overlooked. (Significantly, Ton That Tiet’s modernist score ranges from a solo flute that sounds Vietnamese to the equivalent of early Stravinsky.) The problematic second section of The Scent of Green Papaya, when the heroine becomes enraptured with her well-to-do, westernized employer, seems as much a product of this background as the horrific sense of third-world squalor and cruelty that pervades Cyclo, in which Tran sometimes seems to be as much a horrified Western tourist as the majority of his viewers. Of course the fact that he wanted to shoot his first feature in Ho Chi Minh City but wound up in a French studio for budgetary reasons also has to be taken into account.

It’s a tribute to Tran’s vision that for all the radical differences in tone and texture and scale between The Scent of Green Papaya and Cyclo both emerge as essentially expressionist works — movies taking place inside the filmmaker’s head. But if the first film most often suggested a peaceful, meditative reverie, the comparably fluid Cyclo unfolds like a protracted nightmare.

All the characters in this nightmare are nameless. The hero is known as the Cyclo (Tran notes, “For me, the term refers equally to the driver and his vehicle”), but the grandfather and two sisters he lives with at the beginning of the film don’t even have colorful labels; they’re identified in the script, published last year in France, as the Grandfather, the Little Sister, and the Sister (Tran Nu Yen Khe, the filmmaker’s wife, who played the lead in The Scent of Green Papaya).

The boss the Cyclo works for is the Madam and her beloved retarded son is the Crazy Son. The pimp who also works for her, and who takes the Cyclo under his wing after his pedicab is stolen, is known as the Poet (Tony Leung-Chiu Wai) because he writes poems, some of which we hear him recite offscreen; two of his sidekicks are called Tooth and Knife, and these labels feel like descriptions rather than nicknames. An assassin who slits people’s throats while singing to them is the Lullaby Man; two of the Sister’s clients are the Urine Fetishist and the Foot Fetishist.

The story, such as it is, doesn’t unfold within any discernible time frame; events succeed one another, but we don’t know how much time passes between them. Emotionally and thematically, some of the characters come to seem interchangeable: the Cyclo identifies himself at the outset as his father’s successor, but the Poet and the Crazy Son function as alternate versions of the Cyclo’s father.

Tran has written that both the Cyclo and the Poet “are united by innocence. The Poet had lost his innocence when he chose a life of crime in order to escape mediocrity and poverty, and is drawn to The Cyclo and the innocence he still possesses.” The Crazy Son paints himself yellow, sending the Madam into a rage against the employee who’s supposed to be taking care of him. Then, after the Crazy Son is run over by a truck, the Cyclo, ordered to commit a murder, takes drugs, goes on a rampage, then paints himself blue (like Godard’s Pierrot le fou); the Madam winds up cradling and singing to him just as if he were the Crazy Son.

Part of Cyclo‘s voluptuous mystery is that it unravels simultaneously like a documentary and an expressionist or surrealist vision. (Expressionist: a sense of inside where nothing is safe and a sense of outside where nothing is safe, where the two realms are perpetually linked by camera movements, where everything winds up feeling enclosed, malignant. Surrealist: a pervasive sense of the uncanny, so that the unexplained crash of a helicopter on a city street or fragmented close-ups of a ten-dollar bill — two of the many passing signifiers of an American invasion that’s never even alluded to in the dialogue — register as both incongruous and fantastical, and the many overhead views of the teeming streets from balconies recall shots from Un chien andalou.) It’s impossible to determine where physical reality leaves off and metaphysical unreality begins; with the camera often in continual motion, a scene can begin on one plane of reality and end on another.

I’m not trying to deny that Cyclo, for all its consummate mastery, has problems. It never tries to glorify the violence or the various kinds of degradation it shows, but it doesn’t have a discernible social agenda either, and there are times when its horrors could be said to be indulged in, perhaps even nihilistically celebrated (though never exploited as they would be in a Hollywood movie). Tran has said that he wanted to show all of the violence “with great tenderness,” and I suppose on some level he has. This is a humanist film even if it doesn’t always wear its heart on its sleeve; it never desensitizes one to cruelty the way Quentin Tarantino’s features do, and it never allows one to identify fully with any of its characters.

But it’s a movie that rubs my middle-class nose in things that frighten or appall me about the third world without ever suggesting there’s any solution, just as the second part of The Scent of Green Papaya rubbed my nose in colonialism. I have to admit that one aim of art is to force us to look at things we’d rather not know about, but I’d feel more comfortable with Tran’s baroque hell if I could define what he wanted me to see beyond a loss of innocence. I’m also less than comfortable with Tran Nu Yen Khe’s nonstop goofy grin, which was also present throughout The Scent of Green Papaya, and which her husband at times seems to employ as an all-purpose piece of decor; nor do I know what to make of his compulsive use of fish and lizards. But there’s no denying that Cyclo is a visionary piece of work, shot through with passion and poetry.

Cyclo originally ran 129 minutes, and I saw it at that length a little over a year ago. Assuming that the preview copy I recently saw is the same version as the print showing this week at the Music Box, it’s been cut by five minutes. Missing is a climactic sequence in which the Sister — a virgin the Poet has turned into a prostitute who caters to the kinky tastes of clients without having sex with them — is raped by a sadistic businessman (the Handcuff Man), who’s then murdered by the Poet. Other shots may be missing as well (the French script is clearly longer than Tran’s final cut, so it isn’t a conclusive guide).

I have no way of knowing whether the cuts in Cyclo were made with Tran’s consent, but Tony Rayns’s review of the film in the April 1996 issue of Sight and Sound implies that it showed uncut in England, which leads me to conclude that CFP, the U.S. distributor, is probably responsible for any changes. Given the present critical climate for “difficult” movies, I suppose we should be grateful that Cyclo is opening at all, and given the unpleasantness of much of the movie, I suppose one could argue that abbreviating it is doing the audience some kind of favor. But is it?

I was horrified when a valued colleague and friend at the Village Voice recently gave her blanket endorsement to Miramax’s recutting two pictures that played at the New York film festival, Billy Bob Thornton’s Sling Blade and Chen Kaige’s Temptress Moon, approving both new versions before she even saw them. And at Cannes this year an even more prominent critic from the New York Times told me she thought Harvey Weinstein would have “improved” Dead Man if Jim Jarmusch had allowed him to recut the picture. I think it’s obscene to grant critical approval to any distributor who proceeds in this fashion. In the case of Cyclo, where each character is brought to a kind of grisly apotheosis, these cuts unquestionably do harm; certainly the Sister’s role in the overall dramaturgy has been obscured and confused. Because a year has passed since I saw Cyclo complete and because I’ve seen hundreds of other movies in between, I’m ill equipped to be more specific about the damage done. But the moment critics or other spectators willingly hand over the scissors to distributors — especially if this entails taking them away from filmmakers of the caliber of Thornton, Chen, or Tran — they might as well hand over their voices and brains too.