From the Chicago Reader (April 30, 1993). — J.R.

MY NEW GUN

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed and written by Stacy Cochran

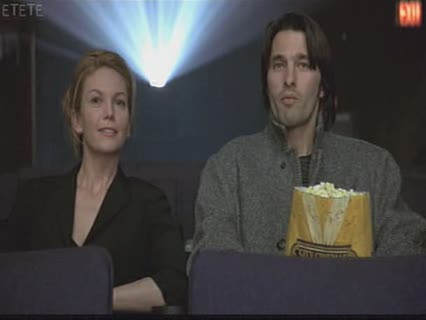

With Diane Lane, James LeGros, Tess Harper, Bruce Altman, Maddie Corman, Bill Raymond, and Stephen Collins.

I finally got to feel that I had to unpack large crates by swallowing the excelsior in order to find at the bottom a few bent and rusty nails, and I began to nurse a rankling conviction that detective stories are able to profit by an unfair advantage in the code which forbids the reviewer to give away the secret to the public — a custom which results in the concealment of the pointlessness of a good deal of this fiction and affords a protection to the authors which no other department of writing enjoys. — Edmund Wilson, “Why Do People Read Detective Stories?”

In the half century that has passed since this famous long sentence was written, it seems that a lot more than detective stories has fallen under the kind of protection Wilson objected to. Miramax’s campaign to protect the “surprise” of The Crying Game has been so vociferous that one feels it may only be a matter of time before the clergy starts inveighing against tattletale reviewers.

A local organization of which I’m a member, the Chicago Film Critics, has joined the fray. When I participated in a roundtable at Columbia College devoted to the “ethics” of film criticism a couple of weeks ago, some of us were a bit shocked to discover what the event’s publicity listed as a key ethical issue in film reviewing. It wasn’t, say, Siskel and Ebert routinely reviewing all the new Disney pictures on a national TV show produced by Disney, or morals expert Michael Medved being hired by studios to give advice about features he will later review, or radio “reviewer” Jeff Craig periodically applying superlatives to movies he hasn’t seen — all typical practices that enjoy guiltless rides in our happy film culture. No, the ethical crisis we were asked to contemplate was that critics who wanted to say something substantive about The Crying Game months after its release risked giving away its surprise (and thereby depriving Miramax of the right to a few more dollars).

Considering that Miramax is famous among distributors for recutting pictures and forcing filmmakers to revise portions of them — so that sex, lies and videotape, for instance, now has a happy ending only because the company ordered one — it’s interesting that the industry’s secret censors and editors are now rewriting our ethical codes. In time, perhaps, distributors like Miramax can furnish their own reviews and reviewers, though many readers will probably be unable to notice any change.

The so-called surprise in The Crying Game has been described as the movie’s “payoff”; it isn’t the ending, which is actually quite conventional. This peculiar assumption that we all go to movies for precisely the same reasons suggests that Miramax has finally succeeded in manufacturing its own audience.

There are no real surprises and no payoffs in My New Gun, a first feature by independent filmmaker Stacy Cochran, at least in the terms that such things are normally understood. But I was still pretty surprised, even baffled, to discover that the movie starts off as an unconventional satirical comedy and ends up as a highly conventional drama from which all hints of satire have been drained away. And as a rule, the more we learn about the characters, the less we care about them. Could this be because Fine Line, the distributor, decided to perform a Miramax on the original material, or is it because the writer-director has something more subtle up her sleeve that I still haven’t figured out?

Frankly, I don’t know. All I can state with any assurance about My New Gun is that by the time one has swallowed all its excelsior, the few bent and rusty nails one discovers at the end can’t hold the vehicle together. The movie is not a detective story, I hasten to add, but it proceeds mainly through plot-related mysteries of various sorts — though the clearing up of some of these mysteries ultimately dissipates most of the interest the story has. Consequently, if My New Gun is about its story — and according to the “ethics” I’ve been outlining above, it can’t possibly be about anything else — there’s no reason I can think of for seeing it.

But what if My New Gun is about something other than its story? What if it happens to be about the way we live?

In the opening scene of the picture a young housewife and her radiologist husband, Debbie and Gerald Bender (Diane Lane and Stephen Collins), are entertaining Gerald’s partner Irwin Bloom (Bruce Altman) and his girlfriend Myra (Maddie Corman) in their suburban house in New Jersey. Gerald is mixing martinis in the kitchen as Irwin is telling Debbie that he and Myra are “tying the knot.” At this point Gerald drops a glass pitcher on the kitchen floor, then calls Debbie in to clean it up. Fadeout. It’s the first point the movie makes: sexist Gerald wouldn’t dream of cleaning his own messes up. The acting and directing styles already impart a sense of uncertainty and missed connections that may be simultaneously this movie’s strongest and weakest suit: the fact that all the characters are adrift in relation to themselves and one another seems to motivate the relative arbitrariness of the plot at the same time it suggests that the movie itself may be partially out of control.

Just afterward Irwin cites his recent gift to Myra, apart from an engagement ring — a .38 revolver. “She has to go through Port Authority every night,” he explains. Myra proudly takes the pistol out of her purse to show it off.

When we next see the Benders, in the daytime on their sun porch, in long shot, Gerald proposes getting a gun for Debbie as well. When she objects to the idea, he informs her it’s too late — he’s already gotten her one. A little later, we see Debbie interrupt her vacuuming to sneak a look at her new gun in the drawer next to the bed. She sits brooding in a chair, looking at it, obviously distressed. Later she interrupts their lovemaking to say, “Honey, I’m distracted. I don’t feel safe with it here.” Still later she wakes screaming from a nightmare in which the gun goes off. The phone rings; it’s Skippy (James LeGros), her best friend, who lives with his mother in a nearly identical house across the street, wondering if she’s OK.

So far we have the makings of a major subject. If we think about the recent multiple deaths in Waco, Texas — all the consequence of armaments possessed by the religious group under siege and by the government agents trying to root them out — or about the weapons of both LA’s policemen and rioters, or about the massive sales of armaments to people all over the world, it would seem that My New Gun is about a habitual American form of business-as-usual thinking that makes supposedly civilized people and supposed sociopaths virtually interchangeable, apart from their classes and uniforms.

For a while this is what the movie appears to be about, which nurtured my hope that it was going somewhere. The fact that Cochran avoids close-ups helps to distance her characters — even to some degree Debbie, who functions mainly as our identification figure — and to turn them into suburban caricatures, milder versions of the adult gargoyles in Parents. But the fact that Debbie herself seems to oscillate between being a surrogate for the viewer and a satirical target unhinges the comic and mystery elements in the story, and the movie never quite recovers from the confusion. (On the whole, Cochran seems much surer of her comic footing when handling the males; the vagueness of the appropriately named Skippy and the glibness of Gerald and Irwin are both exploited to comic effect. But the women tend to slide all over the place from scene to scene.)

After reluctantly and awkwardly doing some target practice in the woods at Gerald’s insistence, Debbie goes shopping with Skippy and expresses her worries about the new gun. Feeling obliged to make a purchase at the supermarket cash register, she picks up a magazine; when she finds herself without change, Skippy distractedly forks over a hundred-dollar bill. Two things are suggested: that Skippy, a reticent, mysterious fellow, is romantically interested in Debbie, and that he may be involved in some criminal activity.

Later Debbie is seen doing the dishes, and Skippy appears outside the kitchen window and asks to borrow her gun. She refuses, but when Gerald appears Skippy takes advantage of her embarrassment, claiming he wants to borrow a cup of sugar. He then asks to wash his hands upstairs, where he finds and pockets the gun.

The next day Debbie is confronted by Gerald after he comes home and finds the gun missing. She tells him what happened, and Gerald, so angry that he throws an apple at their front door, demands that she get it back and accompanies her to Skippy’s house. Skippy is reluctant to turn it over, but eventually does. While walking away, Gerald, still incensed, accidentally shoots himself in the foot.

After spending all night with Gerald in the hospital, Debbie stops off at the fast-food outlet where Skippy works and faints almost immediately. While Skippy revives her with a cup of Coke and offers to feed her onion rings — “It’s a vegetable,” he insists — his coworker goes out to Skippy’s car, where he apparently nods off on drugs and causes the car horn to blare continuously. Skippy goes out to the car and drives off. Debbie returns to the hospital, then goes home, where Skippy, claiming that his coworker had an appendicitis attack, asks to borrow her car to take his mother to the airport.

As the plot develops we eventually find out why Skippy wants a gun, but not why he has hundred-dollar bills or what happened to his coworker. At a climactic juncture Debbie steals another gun to save his life, which she manages to do without a single shot being fired. By this time Gerald has left her for another woman, whom we barely know, and Debbie has begun a serious affair with Skippy; we also learn that Skippy’s mother is a famous country-western singer addicted to prescription drugs and married to — but estranged from — a lunatic. For some reason I can’t fathom, we also discover that Gerald was stricken with food poisoning while he was in the hospital.

Somehow the relevance of guns in all of this top-heavy and untidy plot material tends to get lost. When Cochran brings a gun back for the finale, it harmlessly saves the day, pretty much negating and contradicting everything that went before. What remains, more or less, is the overall impression that none of the characters knows very much about the others, and that we know very little about any of them. This is an excellent potential premise for another movie, and maybe someday Stacy Cochran will make it.