From the Chicago Reader (April 1, 1988). — J.R.

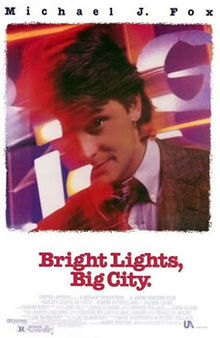

BRIGHT LIGHTS, BIG CITY

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed by James Bridges

Written by Jay McInerney

With Michael J. Fox, Kiefer Sutherland, Swoosie Kurtz, Phoebe Cates, Frances Sternhagen, Tracy Pollan, Jason Robards, John Houseman, Dianne Wiest, and William Hickey.

Considering the thinness of Jay McInerney’s 1984 best-seller, one might imagine that the movie version would stretch out the material, or at least fill in some of the blanks. But by and large, the original text is treated as if it were engraved in marble, and I doubt its fans will have any cause for complaint.

If Melville, Twain, Faulkner, Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Algren, Updike, and Styron have never received a tenth of the respect from Hollywood accorded here to Jay McInerney, this may be because, unlike McInerney, they are writers whose styles and formal structures are easily lost in translation. McInerney’s book, written in the present tense and in the second person, is already aiming for the immediacy and easy identification available from a movie, so most of the work of the filmmakers in putting it across is relatively sweat-free. In fact, given the charisma of Michael J. Fox and the spit and polish of director James Bridges — not to mention the music of Donald Fagen (of Steely Dan) and the cinematography of Gordon Willis — it could easily be argued that the movie fulfills the novel’s designs better than the novel does. But to what end?

In a deft act of self-positioning, the novel is prefaced by a quote from The Sun Also Rises, and follows a narrative trajectory that roughly parallels that of The Catcher in the Rye: that is, on the pretext of saying something about a “lost generation,” it follows the obsessions and wanderings of a young hero cut loose from his bearings over a few confused days in Manhattan, in flight from his own despair and nervous collapse (as well as from his family). The novel’s ideological project, on the other hand — to validate the yuppie ethos and life-style (self-interest, cocaine, urbanity, enlightened disdain for one’s surroundings) in literary terms — is a far cry from either Ernest Hemingway or J.D. Salinger, however much the book may cop a free ride on certain mythological associations made with both authors.

The differences begin to stand out if one compares the nameless hero of McInerney’s novel (called Jamie in the movie) with the older Jake Barnes in The Sun Also Rises — physically, mentally, and spiritually debilitated by his war experience — and with the younger Holden Caulfield in The Catcher in the Rye, a prep school flunk-out and social outcast who is recounting from a sanitarium what led up to his nervous breakdown. McInerney’s hero, by contrast, is a young writer whose wife leaves him after she achieves success as a fashion model; he then loses his job as a fact checker for a magazine (a thinly disguised New Yorker in book and film alike); his third tragedy, which we learn about more gradually, is that his mother died of cancer a year earlier.

One might argue that any American writer since Hemingway and Fitzgerald who deliberately sets out to create a portrait of a “generation” is already doomed to mediocrity. (Our best novelists, from Faulkner to Pynchon to Styron to Percy, have always had bigger fish to fry — especially since the very notion of “generations” has been reduced and multiplied by media hype to mean approximately one new target audience per season.) But whether we accept this caveat or not, it seems reasonable enough to claim that Bright Lights, Big City–the novel and the movie — does capture the sensibility of a particular generation, in however reductive a fashion.

For starters, McInerney’s hero is the reverse of the existential hero, who is defined by what he is and does; Jamie’s self-definition is almost exclusively a matter of what he has — good looks, flip attitudes, a wife, a mother, a prestigious job, a steady supply of coke — so that his crisis is precipitated when he loses at least half of the above possessions. The fact that he isn’t a very good fact checker — or that he lies in his resume about being proficient in French, which helps to bring about the debacle that leads to his getting fired — isn’t supposed to count for much, for what the hero has (as opposed to what he does) is largely a matter of public appearances. (He also pretends to various acquaintances and family members that his wife hasn’t left him.)

The ritual significance of mirrors and dollar bills in coke snorting (allowing you metaphorically to see and price your own identity and possessions) and the symbolic significance of bathrooms (dirty secrets and anal retentiveness) aren’t lost on Bridges, which is one reason why the movie conveys the yuppie ethos better than the novel. (While the book curiously makes no attempt to convey the experience of coke, despite a plethora of references to the drug, Bridges does a few sharp and sudden sound-editing cuts — from toilet stall to dance floor, from street to subway train — to approximate the effect of rushes.) On the other hand, the movie intermittently tries to be a little more moralistic than the book about the self-conscious decadence that both traffic in. When the hero in the book asks his younger brother Michael, “You want to do a few lines?” Michael shrugs and says, “Why not?”; in the movie, he pointedly declines and opts for a shower instead. Similarly, when the hero in the movie is saying good-bye to his best friend and cokemaster, Tad Allagash (Kiefer Sutherland), at a decadent party where he’s just encountered his wife, Amanda (Phoebe Cates), he delivers the following homily, which isn’t in the book: “I just thought of something: you and Amanda would make a terrific couple.”

The moral grading of the characters in book and film alike is fairly cut and dried: Women who are exclusively maternal figures — the hero’s mother (Dianne Wiest) and his sympathetic, older office mate Megan (Swoosie Kurtz) — are unambiguously good. Women who have more power than the hero and no maternal instincts — his wife and the boss who fires him (Frances Sternhagen) — are unambiguously evil; only the sketchy figure of Allagash’s cousin Vicky (Tracy Pollan) escapes this rigid patterning, and she exists simply as a friendly platitude. The older men, on the other hand — ranging from the alcoholic magazine editor (Jason Robards) to the prissy editor in chief (John Houseman briefly impersonating the New Yorker‘s William Shawn) to the bum who sells the hero a ferret (William Hickey) — are all castrated father figures, while the hero’s actual father is nowhere to be seen.

The self-conscious literary device that is used to wrap up this parental theme in a bite-size package is the “Coma Baby” — a dream-figure gleaned from a series of New York Post headlines that becomes the hero’s nightmare vision of his own helplessness. In the novel, this functions mainly as a free-floating signifier, because the death of the hero’s mother and its significance are kept under wraps until the climax, when her memory emerges like a deus ex vagina to save his soul. More sensibly and judiciously, the movie doses the present action with mini-flashbacks of her on her deathbed, and then gives us a Coma Baby dream sequence that beats the one in the book by miles.

The movie’s best improvement on the book, however, is Michael J. Fox, if only because he makes the hero’s self-absorption seem less apparent and therefore less repellent. Some of this is brought about by a repositioning of the hero’s writerly persona; the movie is divided into sections introduced by typed-out captions for each successive day, and this dilution of the hero’s literary self is both merciful on its own terms and superior to the book’s arch chapter titles. It also frees us somewhat from the hero’s limited self-understanding and allows Fox to give the character some pathos as a loose cog in the world rather than as a self-pitying weaver of his own mythology — a snob whose “sophistication” is defined by his disdain for a bald-headed woman in a disco and his affection for croissants and the New York Times. (McInerney’s use of second person — sparingly retained in the movie — does nothing to distance his narrator’s voice; unlike Michel Butor’s more innovative use of second person in La modification, translated as A Change of Heart, or Salinger’s first-person impersonation of Holden Caulfield in Catcher, it merely functions as a sneaky and displaced use of an unmediated “I.”)

Yet despite all these cosmetic improvements, what does Bright Lights, Big City finally add up to? Fox’s best stretch as an actor — apart from some emotional head-pounding when the hero argues through a closed bathroom door with his brother — comes during a lengthy monologue that he delivers in Megan’s apartment while guzzling wine, in which he tells the story of his failed marriage. Behind him is a spectacular view of the bright lights of the big city seen through the windows — an apotheosis of all the fake big-city skyline backdrops that have graced thousands of other Hollywood movies, only slightly less impressive than the one seen in Hitchcock’s Rope. Bridges is smart enough as a director to know that it’s fake, and to use this backdrop to counterpoint Fox’s confession of his own self-deceptions.

But in the final analysis, the backdrop makes the confession phonier rather than truer — not because Fox isn’t a good enough actor, but because the lines remain as trite and two-dimensional as the city behind him. (“If you strip away the phony tinsel of Hollywood,” Oscar Levant once said, “you’ll find the real tinsel underneath.”) Just as in the would-be epiphany of the final scene, when the hero solemnly swaps his sunglasses with a trucker for a piece of bread, the reach for profundity and a sense of unexplored depths only makes the shallowness seem shallower. With the best will and effort available, the filmmakers can make their sow’s ear glitter with mirrors and bright lights, but it still won’t hold pocket change.